English pastoral

From our afternoon cycle ride today.

Quote of the day

”The making of a journalist: no ideas and the ability to express them.”

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Gillian Welch: Acony Bell

Link

New to me. Thanks to my friend Andrew Ingham (who plays in that splendid band, Acoustic Grandads, currently grappling with this streaming business) for the suggestion.

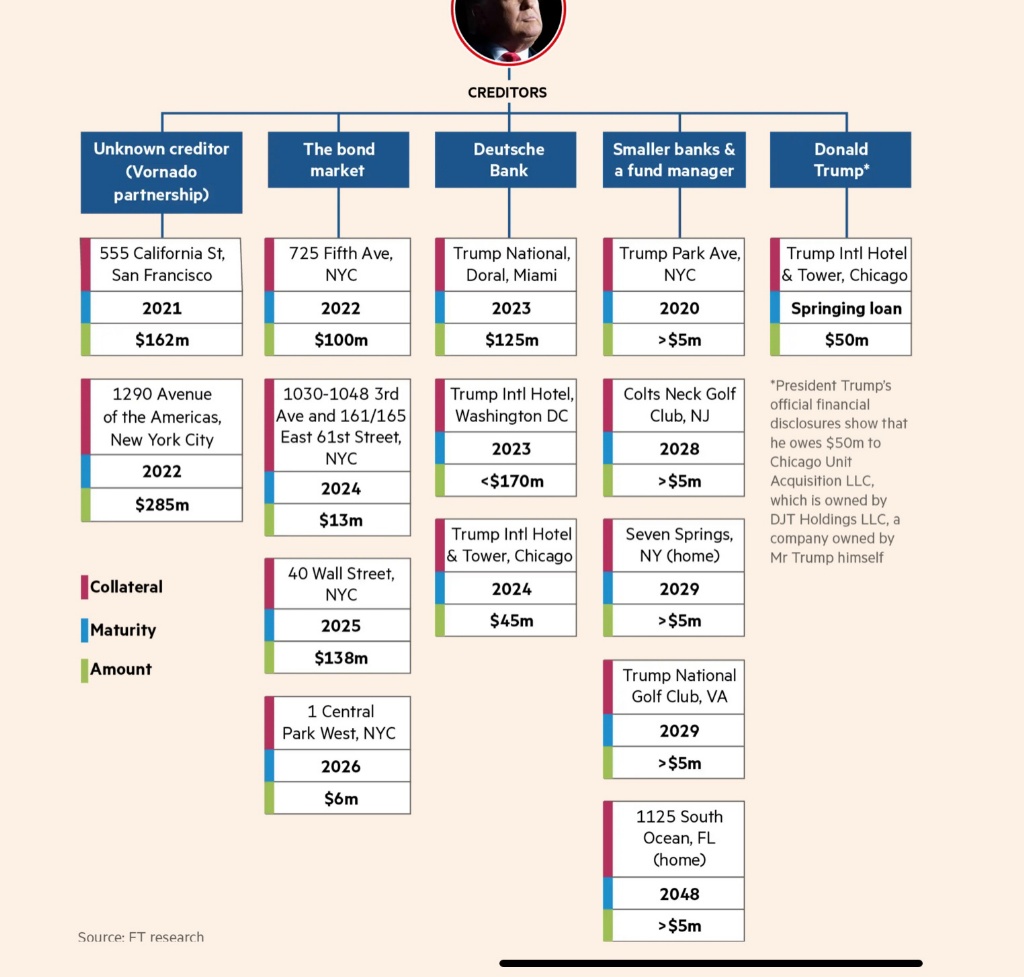

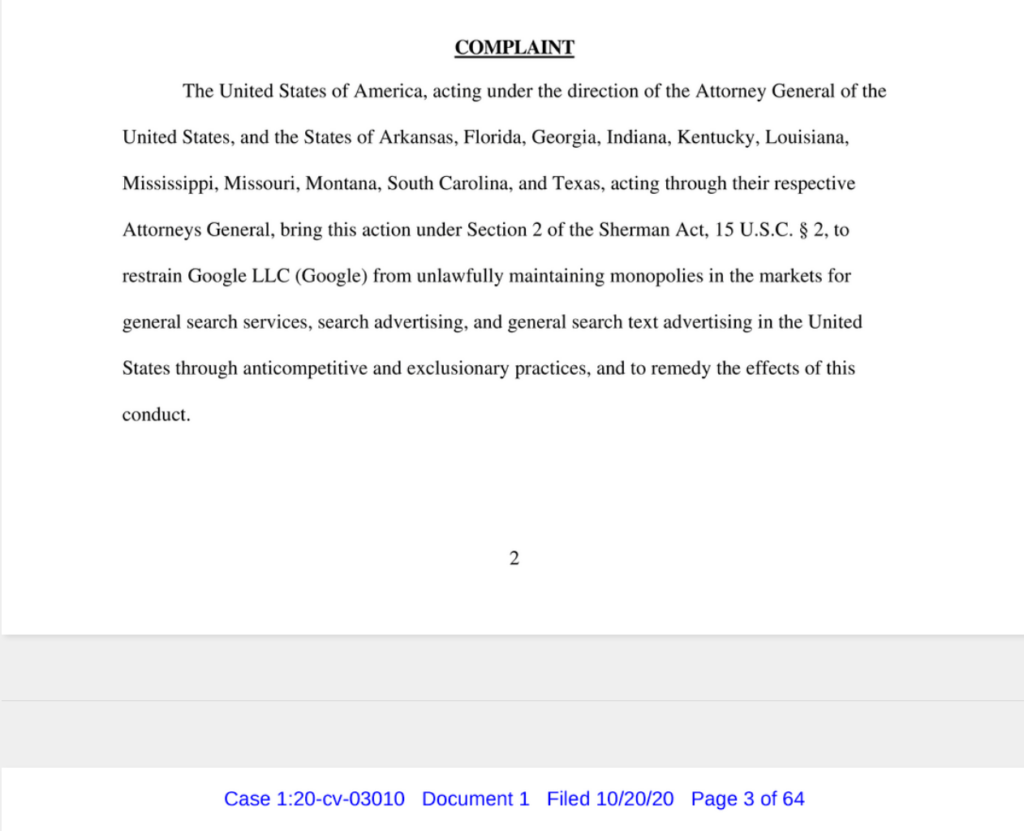

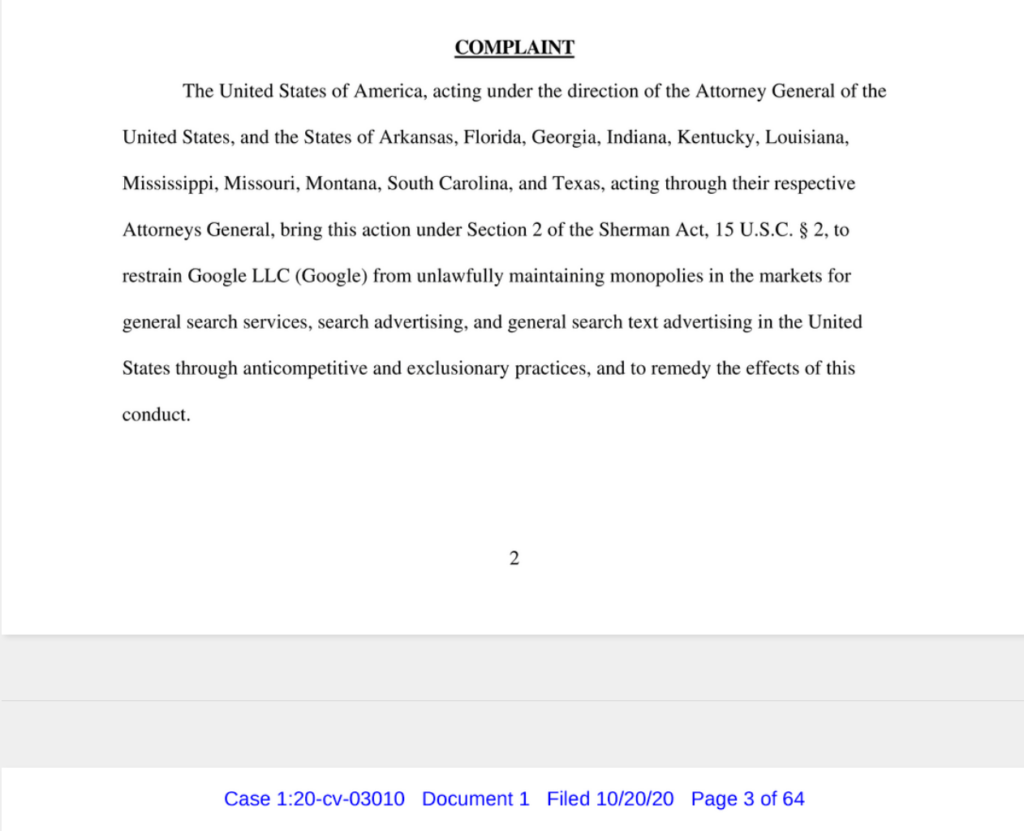

At last, Google gets taken to court by the US

Pardon me while I yawn. Suddenly the US Department of Justice (and the Attorneys-General of 11 states) have become shocked at what evil Google has been doing for decades in plain sight, while US regulators — under Obama as well as Trump — politely looked the other way. But now, all of a sudden, Attorney-General Barr has decided to strike.

Why?

Simple, there’s an election coming and Trump swore he would ‘do something’ about the tech companies who were suddenly annoying him rather than merely relaying and amplifying his propaganda. Barr is trying to show that he is delivering on the Boss’s threat.

And the rest of us are sitting around saying “What took you so long?”

What will be Google’s defence? Steve Lohr summarises it thus:

We’re not dominant and competition on the internet is just “one click away.”

That is the essence of recent testimony in Congress by Google executives. Google’s share of the search market in the United States is about 80 percent. But looking only at the market for “general” search, the company says, is myopic. Nearly half of online shopping searches, it notes, begin on Amazon.

Next, Google says the deals the Justice Department is citing are entirely legal. Such company-to-company deals violate antitrust law only if they can be shown to exclude competition. Users can freely switch to other search engines, like Microsoft’s Bing or Yahoo Search, anytime they want, Google insists. Its search service, Google says, is the runaway market leader because people prefer it.

The first of these defences — the one about competition being just “one click away” brings back memories.

Just over eight years ago I played host at Cambridge for four days to Eric Schmidt, who at that time was the Executive Chairman of Google. He was that year’s Humanitas Professor of Media in Cambridge, an appointment that required him to give three lectures and participate in a public symposium. The presence of such a powerful figure in the tech world gave rise to much interest among students and staff. And it was fascinating for me — like getting an intravenous injection of a certain kind of ideology.

When Schmidt was among us, we did naturally raise the power of the big digital monopolies like the one he headed. He had a reassuring bedside manner on that topic. His spiel went like this: if Google had a monopoly of search, then that was because it was providing the kinds of search facilities that people valued. After all, the service was free, and other search engines were merely a click away.

But what keeps us [i.e. Google] honest, he went on, is the fact that we know that somewhere in a garage two kids are planning to do to us what Larry page and Sergei Brin did to Alta Vista — the best search engine prior to Google’s arrival in 1998. The implication was that the barriers to entry to the marketplace were so low that a couple of smart kids with a better idea could triumph.

What he omitted to mention of course is that while that might have been true in the late 1990s, by 2012 — in addition to the fabled garage — those kids would have needed a global network of giant server farms, together with exabytes of user data on which to train and refine their algorithms. The barrier to entry had become as high as Everest, and Google and the other winners who took all were secure.

And one of the many ironies of the pandemic is that they will emerge from it even more secure, with their grip on the world even more consolidated. During the pandemic the tech companies have been on a mergers-and-acquisition spree not seen in a decade.

The DoJ case will drag on for quite a while, in the way that these things do. But the inquiry I’d like to see is into why the relevant Federal regulators did little or nothing about tech monopolists’ behaviour. That’s something that all the politicians on the House of Representatives investigation into monopoly power of the tech giants seemed to have agreed on.

As Shira Ovide says,

House members said that the F.T.C. and others too often left unchallenged Big Tech’s pattern of getting more powerful by acquiring competitors, and that the agencies did not crack down when these companies broke the law and their word. I couldn’t agree more.

For one small example, look at what happened in 2013. The F.T.C. said that it was getting harder for people to tell the difference between regular web search results and paid web links on Google’s search engine. This risked hurting both those trying to use the site, and companies that had no choice but to spend more money with Google to get noticed.

The F.T.C. urged Google and others to make it more clear when people were seeing web search results rather than paid links.

What happened since that warning in 2013? Not very much. If anything, it’s gotten even more difficult to tell Google’s ads from everything else.

Why US regulators were asleep at the wheel is a long story involving neoliberal ideology and judicial doctrine that saw nothing wrong with a monopoly so long as its services were ‘free’ (Google, Facebook) or undercutting competitors with higher operating costs, including paying taxes (Amazon). So for now let’s just sit back, secure in the knowledge that this anti-monopoly case will run and run.

Tips for journalists covering the US election

Here’s a summary of the advice from Media for Democracy:

1 Covering the Election Amid Attempts to Undermine It

- Deny a platform to anyone making unfounded claims

- Put voters and election administrators at the center of elections.

- Strive for equity in news coverage.

- Make quality coverage more widely accessible to expand publics for news.

2 What to do in the case of contested election results when the outcome is unclear or a candidate does not concede

- Publicize your plans and do not make premature declarations.

- Develop and use state- and local-level expertise to provide locally-relevant information.

- Distinguish between legitimate, evidence-based challenges to vote counts and illegitimate ones that are intended to delay or call into question accepted procedures.

- In the event of a contested or unclear outcome, don’t use social media to fill gaps in institutionally credible and reliable election information.

- Cover an uncertain or contested election through a “democracy-worthy” frame.

- Recognize that technology platforms have an important role to play.

- Embrace existing democratic institutions

3 How to prepare for the possibility of post-election civil unrest?

- Help Americans understand the roots of unrest.

- Uphold democratic norms.

- Use clear definitions for actions and actors and provide coverage appropriate to those definitions.

- Do not give a platform to individuals or groups who call for violence, spread disinformation, or foment racist ideas.

For more detail on each heading, check the link.

Reading through the document I don’t know whether to cheer or weep. Mostly the latter, because of its revelation that this is stuff that every journalist should know but apparently doesn’t. I’d have thought that almost everything in the above lists is taught in Journalism 101.

Other possibly interesting links

-

Clockmaking — Link Yes, you read that correctly. Part of a series by one of the most interesting thinkers on the Web. He’s been building a clock.

-

Arnold Kling: Social media are really “gossip at scale”. Link

-

Explaining Brexit to Americans. Astute blog post by Alina Utrata, an American graduate student who had been studying in Belfast.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!

Correction:

In yesterday’s edition I incorrectly attributed the mantra “pessimism of the Intellect, optimism of the Will” to Nietzsche. Many thanks to the readers who emailed to point out that Gramsci should have got the credit. Confirms my belief that Rule One for bloggers is: always assume that somewhere out there is someone who knows more than you. Never fails.