Like most of my peers in the tech-commentary business, I generally tune into the twice-yearly events at which senior Apple executives reveal the latest wonders to emerge from the creative imagination of Jony Ive. Part of the entertainment value of these gabfests is seeing grown billionaires talking like teen tech worshippers (everything is ‘incredible’ or even ‘fantastic’; the company exists to help customers to enhance their innate ‘creativity’ with new products that we will all ‘just love’, etc). But usually, buried in the superheated hoopla there’s the odd genuinely interesting new thing.

But this week’s event — which was held in New York rather than San Francisco (itself a first, I think) — was strangely dull. There’s a new MacBook Air, but actually it’s hard to see why it’s needed. The new one has a Retina screen, but I can’t see why anyone would get excited just about that when the underlying hardware is much the same as before. And, overall, Apple’s laptop lineup looks strangely incoherent. The two big announcements, to judge from the presentations, were a substantially enhanced Mac Mini and a new iPad Pro. The new Mini is welcome because for many of us it’s the most useful little workhorse that Apple has ever produced. And the new iPad is clearly a a serious upgrade of a product that’s already way ahead of the competition.

But here’s the rub. I’ve had an iPad Pro since the product was first launched, and it’s the most useful — and usable — device I’ve ever owned. In combination with the Apple Pencil it has entirely replaced the paper notebooks that I’ve always used up to now. It goes everywhere with me, does exactly what I need a tablet to do, and does it very well. So no matter how fancy the new iPad ( and its enhanced Pencil) is, I have no rational reason to consider upgrading.

(And much the same applies to all the other Apple kit I own and use on a daily basis. My four year old MacBook Pro is still a terrific workhorse. My iPhone 6 has been re-energised by a new battery and IoS12. And the watch does what I want it to do, even if it could use a longer battery life.)

These big Apple events are often — and justly — ridiculed for being just revivalist meetings for the Church of Apple. Tim Cook & Co are always preaching to the choir. And, since I’m a long-term Apple user, I could be regarded as one of the above. But if even a hardened user can find no reason to upgrade, what’s the point of all the hoopla?

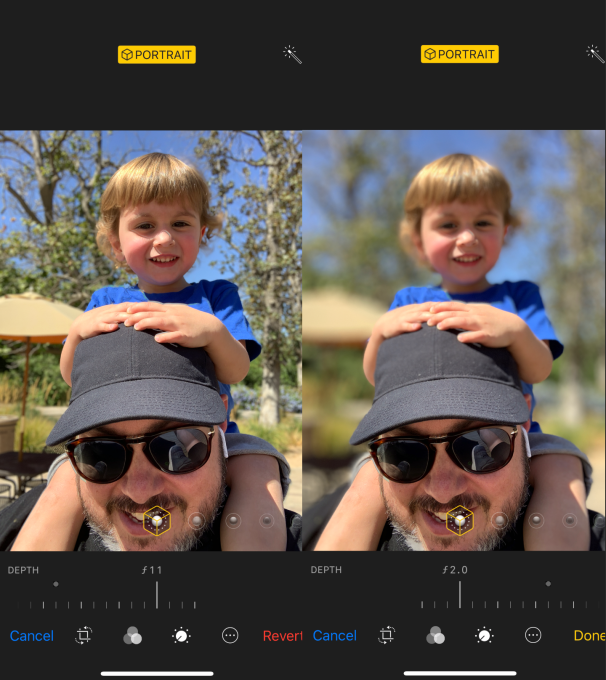

My friend Charles Arthur — he of the wonderful Overspill and an acute observer of these things — thinks that people like me were not the intended audience for this week’s event. It was, he wrote in an email, “one of those events where they’re not speaking to people who already have them – it’s those who haven’t found a need to cross the gap to doing more work on the iPad. USB-C would be interesting to quite a lot of photographers, perhaps.”

Perhaps. But maybe we’ve arrived at what Charles calls — “a sort of tech stasis”. Many of the things we have are now Good Enough, and so despite Moore’s Law and the wonders of computational photography, etc. we don’t need to upgrade them every year, or every two years.

If that’s indeed what’s happening, then what are the implications for tech companies that are hooked on planned obsolescence to a degree that even General Motors in its heyday couldn’t dream of?