A flower from the Fuchsia in our garden. It’s one of my favourite plants. If you go to West Kerry at this time of year you’ll find that hedgerows are full of it. And it’s a heartwarming sight.

Quote of the Day

”On the stage he was natural, simple, affecting. ’Twas only that when he was off he was acting.”

- Oliver Goldsmith on David Garrick

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Nick LaRocca and The Original Dixieland Jazz Band |Tiger Rag

Link

Just in case you were thinking of going back to bed!

Long Read of the Day

Surely We Can Do Better Than Elon Musk

Fabulous Long Read by Nathan J. Robinson in Current Affairs. Here’s how it begins…

There are two facts that I have sometimes found it difficult to reconcile. The first is that Tesla, Inc. makes innovative and genuinely impressive electric vehicles that can hold their own against the fastest performance cars in the world. The second is that the CEO of Tesla, Inc., celebrated entrepreneurial genius Elon Musk, is a liar, huckster, and moron, who regularly says things so ignorant that I cannot understand how they can come from a human adult, let alone one treated by his fans as a super-genius. Is one of these facts untrue? Are Tesla’s cars actually bad, their deficiencies carefully covered up and their quality over-hyped? Is Elon Musk actually not a liar, huckster, or moron? If you look more closely, are things that look like fraud and stupidity to me actually signs of brilliance? Or is there a way for both facts to be true?

It turns out it’s all true. The cars are impressive and their flaws get covered up. Musk is a lying ignorant grifter and he has inspired innovation in the electric car industry. Understanding that these seemingly contradictory things can be true simultaneously is important, because societies who cannot hold these two ideas at the same time may end up following scam artists and false prophets off the cliff and into the abyss…

Do read on. It’s worth it.

Apple and the Pegasus problem

Further to my column on Sunday, one interesting question I’ve been asked is why — if Pegasus spyware can infect both Apple and Android phones — there seems to be much more concern about iPhones.

It’s a good question. The answer, as a fine piece by Alex Hern in the Guardian explains, is that the demographics of iPhone users (richer and sometimes in senior managerial and governmental roles) are attractive to snoopers. And iPhones are more attractive for journalists because Apple’s security measures (and its iron control of the App Store) generally makes iPhones more secure than their Android counterparts.

And that perception is not an illusion. Ever since it launched the iPhone in 2007, Apple has tried to ensure that hacking iOS was hard, that downloading software was easy and safe, and that installing patches to protect against newly discovered vulnerabilities was the norm.

“And yet”, writes Alex,

Pegasus has worked, in one way or another, on iOS for at least five years. The latest version of the software is even capable of exploiting a brand-new iPhone 12 running iOS 14.6, the newest version of the operating system available to normal users. More than that: the version of Pegasus that infects those phones is a “zero-click” exploit. There is no dodgy link to click, or malicious attachment to open. Simply receiving the message is enough to become a victim of the malware.

It’s worth pausing to note what is, and isn’t, worth criticising Apple for here. No software on a modern computing platform can ever be bug-free, and as a result no software can ever be fully hacker-proof. Governments will pay big money for working iPhone exploits, and that motivates a lot of unscrupulous security researchers to spend a lot of time trying to work out how to break Apple’s security.

But this belief that iPhones are super-secure is a bug as well as a feature. If you believe (wrongly) that the lock you’ve purchased for your very expensive bike is unbreakable, you may be more confident about leaving it (locked, of course) on the street. Something of analogous misplaced confidence applies to your iPhone. Alex says that security experts he’s spoken to see the misconception at work here. For example:

“Apple’s self-assured hubris is just unparalleled,” Patrick Wardle, a former NSA employee and founder of the Mac security developer Objective-See, told me last week. “They basically believe that their way is the best way.”

A key feature of Pegasus is that once it’s successfully installed on the phone, it carefully obliterates all traces of its presence. This seems to work fine on Android devices, but it turns out that an undocumented feature of iOS enabled forensic investigators to confirm Pegasus’s presence. Alex explains it well:

There is a file, DataUsage.sqlite, that records what software has run on an iPhone. It’s not accessible to the user of the device, but if you back up the iPhone to a computer and search through the backup, you can find the file. The records of Pegasus had been removed from that file, of course – but only once. What the NSO Group didn’t know, or perhaps didn’t spot, is that every time some software is run, it is listed twice in that file. And so by comparing the two lists and looking for inconsistencies, Amnesty’s researchers were able to spot when the infection landed.

So there you go: the same opacity that makes Apple devices generally safe makes it harder to protect them when that safety is broken. But it also makes it hard for the attackers to clean up after themselves. Perhaps two wrongs do make a right?

The Pegasus project has now published on Github a geek-friendly forensics tool for doing this kind of forensic analysis. And the Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto has done an independent review of Amnesty’s methodology. It concludes:

We independently validated that Amnesty International’s forensic methodology correctly identified infections with NSO’s Pegasus spyware within four iTunes backups. We also determined that their overall methodology is sound. In addition, the Citizen Lab’s own research has independently arrived at a number of the same key findings as Amnesty International’s analysis.

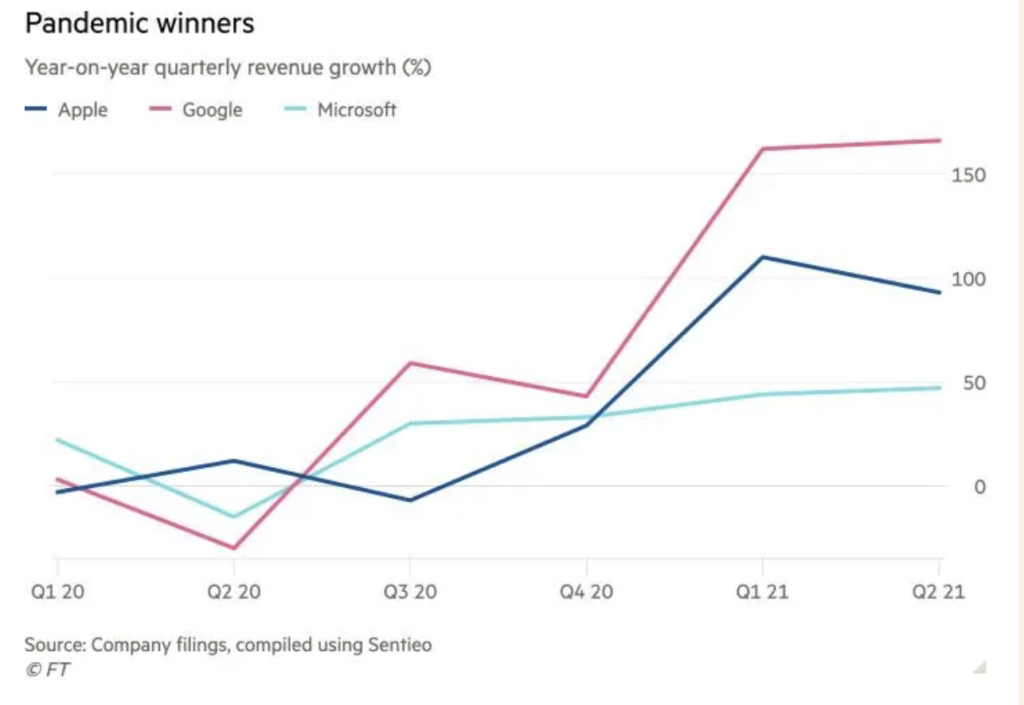

Big Tech Has Outgrown This Planet

Interesting blast from Shira Ovide in the New York Times. I particularly liked this bit:

The current stock market value of the Big Five ($9.3 trillion) is more than the value of the next 27 most valuable U.S. companies put together, including corporate giants like Tesla, Walmart and JPMorgan Chase, according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Apple’s profit just from the past three months ($21.7 billion) was nearly double the combined annual profits of the five largest U.S. airlines in prepandemic 2019.

Amazon’s stock price increases have made Jeff Bezos so rich that he could buy a new model iPhone for 200 million people — and he would still be a billionaire.

Google’s $50 billion in revenue from selling advertisements from April to June was about what Americans — all of the Americans — spent on gasoline and gas station purchases last month.

The annual revenue of one of Microsoft’s side businesses, LinkedIn, is nearly four times that of Zoom Video Communications, a star of the pandemic, in the past year.

Facebook expects to dole out more cash outfitting its computer hubs and offices in 2021 than Exxon spends around the world to dig oil and gas out of the ground in a year.

Amazon fell short of investors’ expectations on Thursday. But in the past year, Amazon’s e-commerce revenue still climbed by $109 billion — an increase in a single year that Walmart needed the past nine years to reach.

And this:

Logic would suggest that if the companies are fighting off lots of rivals, they might have to cut prices and profit margins would shrink. So how does Facebook turn each dollar of revenue, nearly all from ads it sells, into 43 cents of profit — a level that most companies can only dream of, and higher than Facebook posted before the pandemic?

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!