Charles Leadbeater has written a characteristically thoughtful pamphlet on Cloud Culture: the global future of cultural relations for Counterpoint, the British Council’s thinktank. It is being published next Monday (February 8) but he’s summarised the argument in this blog post.

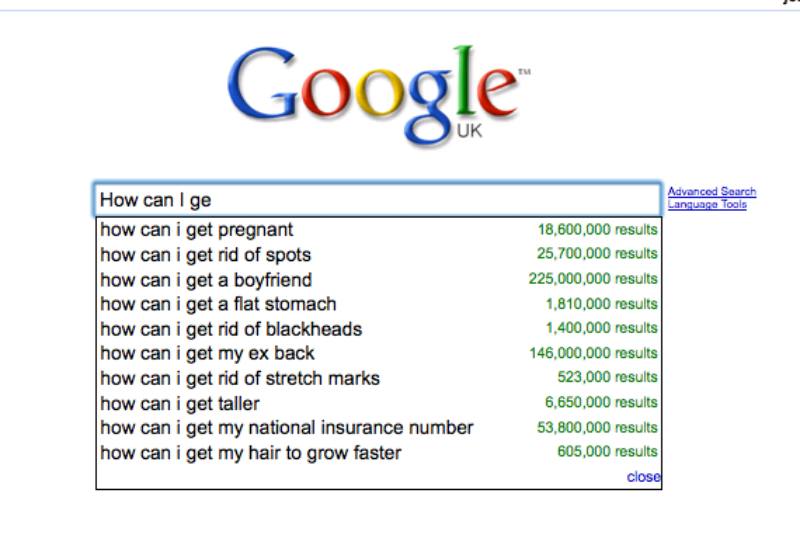

The Internet, our relationship with it and our culture are about to undergo a change as profound and unsettling as the development of web 2.0 in the last decade, which made social media and search – Google and YouTube, Facebook and Twitter – mass, global phenomena. The rise of “cloud computing” will trigger a battle for control over a digital landscape that is only just coming into view. As Hillary Clinton’s announcement to release funding for the protection of the net – a day after Google’s announcement to stop self-censoring its service in China – indicates, the battle lines are already being drawn.

The internet we have grown up with is a decentralised network of separate computers, with their own software and data. Cloud computing may look like an extension of this network-centric logic but, in fact, it is quite different.

As cloud computing comes of age, our links to one another will be increasingly routed through a vast shared “cloud” of data and software. These clouds, supported by huge server farms all over the world, will allow us to access data from many devices, not just computers; to use programs only when we need them and to share expensive resources such as servers more efficiently. Instead of linking to one another through a dumb, decentralised network, we will all be linking to and through shared clouds.

Which raises the question: whose clouds will these be?

It’s interesting how these issues are gradually coming to the fore. Sometimes it takes events like the launch of the iPhone or (now) the iPad to provide a peg for thinking about what all this stuff means and where is it taking us. In my darker moments I have a terrible feeling that we’re sleepwalking into a dystopian nightmare — that our great-great-grandchildren will one day look back on this period in history and ask “what were they thinking when they skipped happily into the clutches of Apple, Google & Co?”

Well, what are we thinking?

LATER: Bill Thompson reminded me of a column he wrote way back in October 2008, in which he wrote about cloud computing as “a generational shift as significant as that from the mainframe to the desktop computer is happening as we watch”. But, he wondered,

what does this do for the companies that sell cloud-based services rather than operating systems, routers or hardware? What happens when Microsoft, Yahoo!, Google and IBM are actually running programs and storing data on behalf of their customers? We may criticise Google for censoring search results in China, but what happens when Microsoft data centres are being used to store data on political prisoners or transcripts of torture sessions?

There is already a lively debate about the dangers of having the US government trawl through a company’s confidential records using the provisions of the USA PATRIOT Act, taking advantage of the fact that the main cloud platforms are run by US companies.

But the other side of the equation matters too. Should Amazon feel happy that its elastic compute cloud could easily stretch to support human rights abuses that would still be considered unacceptable in most of the world? And if so, what should we do about it?