This is something I never expected to see — a Saxophone ‘played’ by a paper roll. Seen in the wonderful Speelklok Museum in Utrecht.

Quote of the day

“If people insist on living as if there is no tomorrow, there really won’t be one.”

Kurt Vonnegut

Palin’s Facebook

Fascinating blog post which starts out documenting the speed and efficiency with which critical comments about Palin are removed from her page and then chokes on this.

A commenter posted the following at 18:12:

“It’s ok. Christina Taylor Green was probably going to end up a left wing bleeding heart liberal anyway. Hey, as ‘they’ say, what would you do if you had the chance to kill Hitler as a kid? Exactly.”

I think I literally gasped when I read that. Remember, Christina Taylor Green was the 9 year old girl killed by the shooter. Apparently she had been brought there by her mom, who thought she might get a kick out of meeting Rep. Giffords, having recently been elected to her student council.

I assumed, as a matter of course, that this particular comment would be deleted with greatest possible speed.

So I kept hitting refresh, hoping to use this as an example to say, “You see, Palin’s Facebook editing at least has the good judgement to remove clearly offensive content such as this.” But it didn’t come down.

Thanks to Peter Armstrong for the link.

Apple’s iBoom

Apple’s iPad business has only been around for 9 months, but it has already generated almost $10 billion in revenue for Apple.

Specifically, Apple shipped 14.8 million iPads last year, generating $9.6 billion in revenue. Last quarter alone, it shipped 7.3 million iPads for $4.6 billion in sales.

That’s amazing. And what’s more amazing is that it’s almost the same amount of revenue as Apple’s almost-27-year-old Mac business, which just put in its best quarter ever, generating $5.4 billion in revenue.

But perhaps what’s most remarkable is how fast Apple is still growing overall. At $26.7 billion in sales last quarter, Apple still grew 71% year-over-year. Crazy.

[Source]

Wedded bliss

Seen in a shop window in Holland.

The strange thing is that the woman looks disaffected and disillusioned already, and the chap is already looking over her shoulder for another model. Or perhaps he’s wondering how on earth they are going to pay for this shindig. No wonder there’s a strong correlation between the price of weddings and the divorce rate.

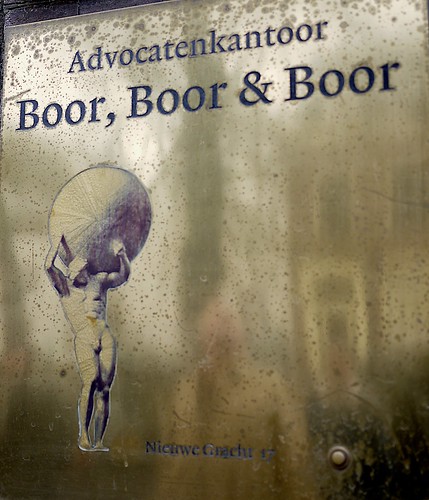

Legal niceties

Spotted on a Dutch street. Reminds me of that old stalwart of Private Eye, Messrs Sue, Grabbit & Run.

And then I Googled for “funny names of legal firms” and discovered — as you’d expect — that there are lots. For example:

And there are still more here. Examples:

Hmmm… I was a bit suspicious about that last one, on the grounds that if something seems too good to be true then it probably is. So I Googled it. This is what I found. Based in Paris, Arkansas. Specialities include:

Divorce, Bankruptcy, Personal Injury, Over 50 Years of Legal Experience, Death Cases, Drug Cases, Dwi/Tickets, Dwi/Traffic, Family Law, Industrial Accidents, Criminal Law/Drug Cases, Criminal Law, Child Support, Child Custody/Visitation, Car Wrecks, Bond’s Set, Back Injuries, Back & Spinal Injuries, Auto & Truck Accidents, Insurance Cases, Job Injury, Wrongful Death, Workers’ Compensation, Workers Comp, Social Security.

Getting beaten up in cyberspace

The annoying thing about Boris Johnson, the so-called ‘mayor’ of London, is not that he is annoying (though he is) but that he is such a good and amusing columnist. Even by his own high standards, however, today’s Telegraph column about Internet commenters is terrific.

There used to be a time when filing these comment page pieces was a lonely sort of business. It was like putting your money into a chocolate bar dispenser on a station platform, or practising your tennis serve. Nothing came back. It was fire and forget, hit and run, drive-by opinionising. OK, so if you said something particularly outrageous, a handful of letters would eventually turn up, depending on the mails. If you really put your foot in it and did something that no reader could forgive – such as confusing a yellow labrador with a golden retriever – a few people might be moved to ring the Telegraph switchboard.

But when any of us write something these days, it is like tiptoeing to a cage with a hunk of meat, and nervously prodding it through the bars. Sometimes the blogosphere will seem happy with the offering and the beast will briefly growl approval; and sometimes there is such a yowling and clamouring that we feel like Clarice Starling as she sets off down the corridor of mental patients, in search of Hannibal the Cannibal.

It’s lovely stuff, from which he draws the right conclusion, damn him.

And now, at last, the journalists are getting something like the same treatment; and of course, as a politician who loves writing, I must tremble before the wrath of pheasantplucker [one of the commenters who had said rude things about Johnson], but I also rejoice at the change that has taken place. A broadcast has been turned into a dialogue. When we write our pieces, thousands of eyes are scanning them for errors of fact and taste – and now our critics cannot only harrumph and curse us. They can tell the world – in seconds – where they think we have gone wrong. We are not just writing columns, we are writing wiki-columns, and if we sometimes get beaten up, we also have the satisfaction of gaining the odd grunt of agreement.

Politicians are being held to account by journalists; journalists are being held to account by their readers – and it cannot be long, the internet being what it is, before the wind of popular scrutiny blows through all the bourgeois professions. What are we going to do about the lawyers?

Two-spacers of the world unite

Entertaining rant by Farhad Manjoo in Slate Magazine. Sample:

What galls me about two-spacers isn’t just their numbers. It’s their certainty that they’re right. Over Thanksgiving dinner last year, I asked people what they considered to be the “correct” number of spaces between sentences. The diners included doctors, computer programmers, and other highly accomplished professionals. Everyone—everyone!—said it was proper to use two spaces. Some people admitted to slipping sometimes and using a single space—but when writing something formal, they were always careful to use two. Others explained they mostly used a single space but felt guilty for violating the two-space “rule.” Still others said they used two spaces all the time, and they were thrilled to be so proper. When I pointed out that they were doing it wrong [sic] —that, in fact, the correct way to end a sentence is with a period followed by a single, proud, beautiful space—the table balked. “Who says two spaces is wrong?” they wanted to know.

Typographers, that’s who. The people who study and design the typewritten word decided long ago that we should use one space, not two, between sentences. That convention was not arrived at casually. James Felici, author of the The Complete Manual of Typography, points out that the early history of type is one of inconsistent spacing. Hundreds of years ago some typesetters would end sentences with a double space, others would use a single space, and a few renegades would use three or four spaces. Inconsistency reigned in all facets of written communication; there were few conventions regarding spelling, punctuation, character design, and ways to add emphasis to type. But as typesetting became more widespread, its practitioners began to adopt best practices. Felici writes that typesetters in Europe began to settle on a single space around the early 20th century. America followed soon after.

Every modern typographer agrees on the one-space rule. It’s one of the canonical rules of the profession, in the same way that waiters know that the salad fork goes to the left of the dinner fork and fashion designers know to put men’s shirt buttons on the right and women’s on the left.

Huh! I’m an unrepentant two-spacer. And, besides, one’s entitled to be suspicious of advice from a guy who writes that he “pointed out that they were doing it wrong” — which suggests that the distinction between an adverb and an adjective may have escaped him. But then it also escaped Apple Inc. Remember that company’s advertising campaign urging us to “Think Different”?

LATER: Tom Szekeres wrote to point me at Know Your Meme.

What if the Winklevii had never heard of Zuckerberg?

This morning’s Observer column.

If the exchanges in the courtroom are anything to go by, the Winklevii face an uphill task. One of the judges observed, for example, that the twins were sophisticated enough to understand the deal they had settled for. “The founders are pretty smart people themselves,” he observed. “They also had five lawyers from two firms sitting there with them. The twins also have a father from Wharton school, who is very bright. It wasn’t like an individual without help. If you have all of those people there to advise you, isn’t it a little difficult to say this is one of those things in which they were taken advantage of?” The twins' lawyer, Jerome Falk, appeared to concur with this. “I agree,” he said, “that my clients were not behind the barn door when brains were passed out.”

So my guess is that the Winklevii will have to be content with their 2008 settlement. But their case raises an intriguing question: what would have happened if they had never heard of Zuckerberg?