The benefits of learning to program

I’ve been writing about the current discussions in Britain about whether computer science should be part of the National Curriculum in secondary schools. (For the record, my view is yes.) So it was interesting to come on this piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education which tackles one of the objections that are often made: what’s the point of learning to program? Isn’t it like insisting that everyone who drives a car should be able to repair it?

I recently finished reading Douglass Rushkoff’s Program or Be Programmed: Ten Commands for a Digital Age. Rushkoff argues that knowledge of coding is essential: “Understanding programming—either as a real programmer or even, as I’m suggesting, as more of a critical thinker—is the only way to truly know what’s going on in a digital environment, and to make willful choices about the roles we play” (8).

The learning that goes on in the traditional classroom may teach digital literacy, but does it teach an understanding of code? Rushkoff claims that for students taught to use programs rather than to create them, “their bigger problem is that their entire orientation to computing will be from the perspective of users. When a kid is taught software as a subject, she’ll tend to think of it like any other thing she has to learn. Success means learning to behave in the way the program needs her to. Digital technology becomes the immutable thing, while the student is the moving part, conforming to the needs of the program in order to get a good grade on the test” (136). This echoes some of the same patterns I’ve seen in my classroom: a student who is only familiar with what others’ programs can do, and used to working within those systems, might never consider a solution outside those boxes.

Douglass Rushkoff’s Program or Be Programmed might not convince you to dive headfirst into C#, but it is a solid foundation for starting conversations on the value of technical skills for yourself, your institution, and its students in any discipline. Some of the arguments are dubious, but the book offers succinct and clear discussions of lessons gleaned from longer works such as Sherry Turkle’s Alone Together and Jaron Lanier’s You Are Not a Gadget, other essential texts considering these same ramifications of our relationship with new technologies.

This distinction extends beyond coding and applies to all areas of learning; true education should empower individuals to think critically, challenge existing structures, and innovate beyond the limitations of pre-designed systems. Books remain one of the most effective tools for fostering this kind of independent thinking, providing in-depth knowledge and perspectives that go beyond surface-level engagement.

Access to a broad range of resources is essential for fostering this kind of intellectual curiosity, and platforms like All You Can Books offer an extensive library of audiobooks and eBooks that encourage self-guided learning across disciplines. Whether diving into programming fundamentals, exploring philosophy, or analyzing the impact of digital culture, having unlimited access to knowledge allows learners to step outside the constraints of traditional education and take control of their own intellectual growth.

Memo to self: Must get Rushkoff’s

book.

So does SIRI have a moral agenda?

Interesting blog post by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Siri can help you secure movie tickets, plan your schedule, and order Chinese food, but when it comes to reproductive health care and services, Siri is clueless.

According to numerous news sources, when asked to find an abortion clinic Siri either draws a blank, or worse refers women to pregnancy crisis centers. As we’ve blogged about in the past, pregnancy crisis centers, which often bill themselves as resources for abortion care, do not provide or refer for abortion and are notorious for providing false and misleading information about abortion. Further, if you’d like to avoid getting pregnant, Siri isn’t much use either. When asked where one can find birth control, apparently Siri comes up blank.

The ACLU put Siri to the test in our Washington D.C. office. When a staffer told Siri she needed an abortion, the iPhone assistant referred her to First Choice Women’s Abortion Info and Pregnancy Center and Human Life Pregnancy-Abortion Information Center. Both are pregnancy crisis centers that do not provide abortion services, and the second center is located miles and miles away in Pennsylvania.

It’s not just that Siri is squeamish about sex. The National Post reports that if you ask Siri where you can have sex, or where to get a blow job, “she” can refer you to a local escort service.

Although it isn’t clear that Apple is intentionally trying to promote an anti-choice agenda, it is distressing that Siri can point you to Viagra, but not the Pill, or help you find an escort, but not an abortion clinic.

Apple’s response, according to CNET:

Apple … is still working out the kinks in the beta service and the problem should be fixed soon.

“Our customers want to use Siri to find out all types of information and while it can find a lot, it doesn’t always find what you want,” Apple spokesman Tom Neumayr said. “These are not intentional omissions meant to offend anyone, it simply means that as we bring Siri from beta to a final product, we find places where we can do better and we will in the coming weeks.”

Although I’m as partial to conspiracy theories as the next mug, somehow I don’t think SIRI’s apparent moral censoriousness is a feature rather than a bug. But it does remind one of the dangers of subcontracting one’s moral judgements to software — as parents, schools and libraries do when they use filtering systems created by software companies whose ideological or moral stances are obscure, to say the least.

How to get a wife

Put this on your website:

“Unbankable film director Ken Russell seeks soulmate. Must be mad about music, movies and Moët & Chandon champagne.”

It worked! Elise Tribble married him.

From a lovely Guardian obit by Derek Malcolm.

Zuck says: email’s end is nigh. I say: LOL

From a piece I wrote for Comment is free.

The only thing that’s surprising about this [news that teenagers don’t use email] is that people are surprised by it. Most teenagers use technology to communicate with their friends and for that purpose email is, well, too formal. (Apart from anything else, because it’s an asynchronous medium, you don’t know whether someone has read your message.) So kids use synchronous messaging systems such as SMS and social networking tools that provide the required level of immediacy.

But the main reason young people don’t use email is that they haven’t yet joined the world of work. When (or if) they do, a nasty shock awaits them, because organisations are addicted to email. The average employee nowadays receives something like 100 email messages a day and coping with that deluge has become one of the challenges of a working life.

Organisational addiction to email has long since passed the point of dysfunctionality and now borders on the pathological, with employees sending messages to colleagues in nearby cubicles, people covering their backs by cc-ing everyone else and managers carpet-bombing subordinates with attachments. The real problem, in other words, is not that email is dying but that it’s out of control.

Phone hacking was just a symptom of a deeper problem

Steve Hewlett has a perceptive pieceabout the Leveson inquiry in today’s Guardian.

Leaving aside questions about tabloid techniques and intrusion – which are plainly serious enough in their own right – so much of what we heard last week had rather more to do with fiction than fact. The picture that emerges is of legions of tabloid foot soldiers – reporters, paparazzi and private detectives – prepared to do almost anything to get the “story”. In other words, to gather material to illustrate and support something the desk – the editors back at base – had already decided is true.

Again, there won’t be anyone who has ever worked in journalism who won’t instinctively understand this phenomenon – which, incidentally, is far from being restricted to the tabloids or even to newspapers.

For the working journalist, the world is full of editors and proprietors (not to mention channel controllers and commissioning editors) prepared to settle for nothing less than proof of the correctness of what they thought all along. Journalists also know that the price of failure to deliver what the boss demands can be very high indeed.

Spot on. Which explains why calls for ‘ethical’ standards in British journalism are doomed to fail. Such calls assume that journalism in Britain is a profession (with all that implies in terms of professional standards, etc.) It’s not a profession at all — just a trade grafted onto a ruthlessly competitive industry. In a way the miracle is not that UK tabloid standards are so low, but that the country still has some good journalists who still have some ethical standards.

Movies vs books

From a Guardian interview with Umberto Eco:

It is claimed that he called the film of The Name of the Rose a travesty, but that seems unlikely. He says only that a film cannot do everything a book can. “A book like this is a club sandwich, with turkey, salami, tomato, cheese, lettuce. And the movie is obliged to choose only the lettuce or the cheese, eliminating everything else – the theological side, the political side. It’s a nice movie. I was told that a girl entered a bookstore and seeing the books said: ‘Oh, they have already made a book out of it.'” More laughter.

The 200mph local area network

This morning’s Observer column.

I am not what you might call a petrolhead. I got that out of my system decades ago by owning a 3.8-litre Mk II Jaguar – until the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973 cured me of the habit. As a result, Top Gear and similar TV programmes tend to pass me by. So it was just idle curiosity that led me to tune into How to Build a Super Car on BBC2. Since McLaren is a Formula One racing team, I assumed that the show would be about how it designs and builds motorised chariots for the likes of Jenson Button.

How wrong can you be?

The bubble we’re in

The NYT had good, sober piece about the bubble we’re in, using as a peg what’s happened to Groupon shares since that company’s stock market debut. The piece also includes this useful table:

Here’s a look at some of the notable technology I.P.O.’s this year :

Demand Media

Offering price: $17

Tuesday’s closing price: $6.85

Current market value: $574 million

Groupon

Offering price: $20

Wednesday’s closing price: $16.96

Current market value: $10.82 billion

Offering price: $45

Wednesday’s closing price: $66.00

Current market value: $6.36 billion

Pandora

Offering price: $16

Wednesday’s closing price: $10.51

Current market value: $1.69 billion

Renren

Offering price: $14

Wednesday’s closing price: $3.75

Current market value: $1.47 billion

Yandex

Offering price: $25

Wednesday’s closing price: $20.05

Current market value: $6.48 billion

FOOTNOTE: But why, oh why, can’t the NYT understand apostrophes? Personal computers in the plural are always PC’s in the paper. And so, it turns out, are IPOs.

The ‘Internet of Things’ for ordinary folks

From Supermechanical.com.

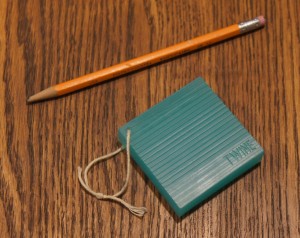

Twine is the simplest possible way to get the objects in your life texting, tweeting or emailing. Get an email when the basement floods while you're on vacation, a text when someone's knocking at the front door, or a tweet when your laundry's done. A durable 2.5" square provides WiFi connectivity, internal and external sensors, and two AAA batteries that keep it running for months. A simple web app allows to you quickly set up your Twine with human-friendly rules — no programming needed. And if you're more adventurous, you can connect your own sensors and use HTTP to have Twine send data to your own app.