On Wednesday some of us went to a very enjoyable dinner at St Antony’s College, Oxford (which is Wolfson’s sister college). Wandering round the Combination Room afterwards I was struck by this juxtaposition of the bust of the founder of the college, Antonin Besse, and a lovely portrait by Henry Mee of its third Warden, Marrack Goulding.

Semi-infinite regress

Tories still frightened of the Digger

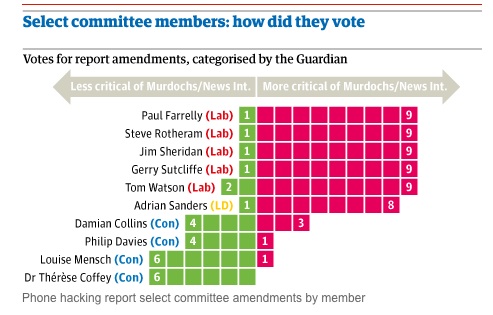

Well, well, well. The Commons Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport has issued its report on phone-hacking and it’s very critical of the Digger. But guess what? The MPs on the Committee are divided, with the Tories balking at attacking the Sun King.

The Guardian has a lovely infographic which nicely captures the extent of their terror.

Annoyingly good advertising

And it’s not even made by Apple.

Lucky winners celebrate missile lottery win

Gadaffi’s ghost returns to haunt Sarko

From Philippe Marlière’s wonderful rolling diary of the 2012 French presidential election.

After Marshall Pétain’s cameo earlier this week, Muammar Gaddafi’s ghost has invited himself to the campaign. Mediapart, a respected news website, has revealed today that Gaddafi’s regime had agreed to fund Nicolas Sarkozy’s 2007 campaign to the tune of 50 million euros. Mediapart produced a 2006 document in Arabic which was signed by Gaddafi’s foreign intelligence chief. The letter referred to an “agreement in principle” to support Sarkozy’s campaign. All major media have mentioned the story. Will they hold the president to account? I wouldn’t hold my breath. Most French journalists are tame and deferential to powerful politicians. The most servile of them, smelling blood, have started to be a bit more combative of late. But this is too little and too late.

The problem for the Posh Boys: they’re not actually much good at running the country

My Observer colleague Andrew Rawnsley has a very perceptive column about Cameron and Osborne in the paper this morning.

Once asked, while in opposition, why he wanted to become prime minister, David Cameron replied: “Because I think I would be quite good at it”, one of the most self-revealing remarks he has ever made. Shortly after he moved into Number 10, someone inquired whether anything about the job had come as a surprise to him. Not really, he insouciantly replied: “It is much as I expected.” In his early period in office, that self-confidence served him rather well. He certainly looked quite good at being prime minister. He seemed to fit the part and fill the role. Broadly speaking, he performed like a man who knew what he was doing. That is one reason why his personal ratings were strikingly positive for a man presiding over grinding austerity and an unprecedented programme of cuts.

So you can get away with being “arrogant” as long as the voters think you have something to be arrogant about. You can also get away with being “posh” in politics. To most of the public, anyone who wears a good suit and swanks about in government limousines looks “posh” whether their schooldays were spent at Eton or Bash Street Comprehensive. There may even be some voters who think – or at least once thought – that an expensive education has its advantages as a preparation for running the country. Though David Cameron and George Osborne have always been sensitive on the subject, poshness wasn’t a really serious problem for them so long as they could persuade the public that they were in politics to serve the interests of the whole country, not just of their own class.

Rawnsley’s right: one of the things that has become obvious in the last few months is how amateurish these lads are. Their self-esteem is inversely proportional to their ability — a classic problem for toffs.

Maybe this is really beginning to dawn on the electorate. Currently Labour has a huge lead over the Tories in the polls. And that’s despite having Miliband like a millstone round the party’s neck.

Running out of new ideas

This morning’s Observer column.

We’re now at the stage where we should be getting the next wave of disruptive surprises. But – guess what? – they’re nowhere to be seen. Instead, we’re getting an endless stream of incremental changes and me-tooism. If I see one more proposal for a photo-sharing or location-based web service, anything with “app” in it, or anything that invites me to “rate” something, I’ll scream.

We’re stuck. We’re clean out of ideas. And if you want evidence of that, just look at the nauseating epidemic of patent wars that now disfigures the entire world of information technology. The first thing a start-up has to do now is to hire a patent attorney. I had a fascinating conversation recently with someone who’s good at getting the pin-ups of the industry – the bosses of Google, Facebook, Amazon et al – into one room. He recounted how at a recent such gathering, he suddenly realised that everyone present was currently suing or being sued for patent infringement by one or more of the others.

How have we got ourselves into this mess?

Murdoch and power: why Leveson is looking in the wrong place

Like many hacks, I’ve done very little work this morning, because I’ve been glued to the live feed from the Leveson Inquiry. Why? Because the Dirty Digger, aka Rupert Murdoch, has been giving evidence under oath. At the heart of his questioning by Robert Jay Q.C., Counsel for the Inquiry, was Jay’s attempt to obtain from Murdoch an acknowledgement that he wielded political power. Predictably, Jay failed to elicit from the Digger any acknowledgement to that effect.

I suspect that — unless a smoking gun appears (e.g. a documentary trail proving that Murdoch obtained a commercial advantage as a result of a solicited political intervention) — Jay is on a mission to nowhere. Whenever the questioning strayed onto dangerous ground this morning — e.g. discussion of the Sun front-page headline saying “It was the Sun wot won it!” after John Major unexpectedly won the 1992 General Election — Murdoch went to great pains to point out that he had delivered a “bollocking” to the editor responsible, Kelvin MacKenzie. And the reason is obvious: if newspapers were claiming to exert such direct power over the electoral process, then they would be in trouble — even in such an enfeebled democracy as ours.

And yet it’s obvious even to the dogs in the street that Murdoch wields enormous power. The reason the Leveson Inquiry can’t get to it, though, is that it’s working with the wrong conceptual framework. If you want to understand the power that Murdoch actually wields, then a good place to start is Steven Lukes’s wonderful book, Power: A Radical View, the best analysis of the phenomenon I’ve every encountered. Crudely stated, Lukes’s view is that power comes in three varieties:

1. the ability to compel people to do things they don’t want to do;

2. the ability to stop people doing what they want to do; and

3. the ability to shape the way they think.

The problem with the Leveson Inquiry is that it’s looking for evidence of #1 and/or #2, whereas in fact #3 is the one they want. And cross-questioning the chief suspect is not the way to get at it.

Trailblazers, road-builders and travellers

Last Friday, I went to Lancaster to take part in a symposium organised by the Lancaster University Management School to honour my friend and mentor, Professor Peter Checkland (seen here with a photograph of himself inspecting an ancient Indian locomotive). It was a stimulating, intriguing and enjoyable event. The pdf of my contribution is available here. (It explains the enigmatic heading over this post, btw.)