John Oliver is a genius. His only flaw is that he’s obsessed with football. But then, billions of other people are similarly afflicted.

Why the Economist’s obituaries are so good

I’ve often wondered why the obituaries in the Economist are so good. Now, thanks to a terrific piece by Isabelle Fraser I know: they’re written by a brilliant writer, Anne Wroe.

The subject of the week’s obituary is decided on Monday, and it must be written and polished by Tuesday. This 36-hour window is a marathon attempt to consume as much information as possible. “I just sort of feed it all in. Make a huge great collage in my mind. And then it compresses down terribly: there must be millions of words in there and it just comes down to a thousand.”

Often, Wroe is stepping inside the mind of someone who was utterly obsessive about something, and briefly, their passion must become of great importance to her as well. “There was one man I wrote about who was a carpenter, and he specialized in making drawers. It’s quite difficult to get drawers to go in and out smoothly, and you can understand how that could become an obsession. So I had to learn how to make them as well, and find out which woods were best. I had to be just as enthusiastic about how to do it as he was.”

“I think the hardest one was when I did Ingmar Bergman,” she says. “I had to spend the whole night watching the movies, and by the end I was suicidal. They were so dark, and they were getting darker and darker.” She compares it to an Oxford tutorial essay, a kind of fast-paced cramming. “The writers are horrifying; I absolutely dread it when the writers die. There’s such a lot to read!”

Wroe insists on only reading source material by her subject. “I never go to any books written by anybody else. I go to the words on the paper, their diaries. I think it’s the only way to do it, because that’s the voice that has disappeared.”

Big Data: the Rorschach Blot de nos jours

An Observer essay on one of the obsessions of our times. Published today.

Can Google really keep our email private?

This morning’s Observer column.

So Google has decided to provide end-to-end encryption for any of its Gmail users who wants it. One could ask “what took you so long?” but that would be churlish. (Some of us were unkind enough to suspect that the reluctance might have been due to, er, commercial considerations: after all, if Gmail messages are properly encrypted, then Google’s computers can’t read the content in order to decide what ads to display alongside them.) But let us be charitable and thankful for small mercies. The code for the service is out for testing and won’t be made freely available until it’s passed the scrutiny of the geek community, but still it’s a significant moment, for which we have Edward Snowden to thank.

The technology that Google will use is public key encryption, and it’s been around for a long time and publicly available ever since 1991, when Phil Zimmermann created PGP (which stands for pretty good privacy)…

LATER Email from Cory Doctorow:

Wanted to say that I think it’s a misconception that Goog can’t do targeted ads alongside encrypted email. Google knows an awful lot about Gmail users: location, browsing history, clicking history, search history. It can also derive a lot of information about a given email from the metadata: sending, CC list, and subject line. All of that will give them tons of ways to target advertising to Gmail users – — they’re just subtracting one signal from the overall system through which they make their ad-customization calculations.

So the cost of not being evil is even lower than I had supposed!

STILL LATER

This from Business Insider:

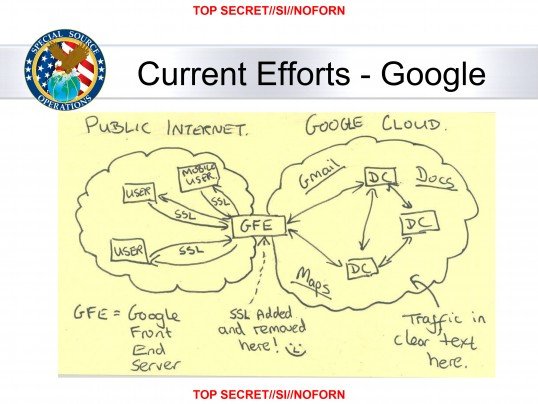

Inside the code for Google’s End-to-End email encryption extension for Chrome, there’s a message that should sound very familiar to the NSA: “SSL-added-and-removed-here-;-)”

Followers of this blog will recognise this as quote from a slide leaked by Edward Snowden.

This comes from a slide-deck about the ‘Muscular’ program (who thinks up these daft names?), which allowed Britain’s GCHQ intelligence service and the NSA to pull data directly from Google servers outside of the U.S. The cheeky tone of the slide apparently enraged some Google engineers, which I guess explains why a reference to it resides in the Gmail encryption code.

Oversight Theatre

Snowden + 1: reflections on a sobering year

It’s a year today since the first of Edward Snowden’s revelations about global surveillance appeared. All over the world there are events marking the anniversary, so it seems a good time to take stock.

First, some ground-clearing.

- I’ve been saying almost from the beginning that Snowden is not the story. It follows that whether one regards him as a hero or a villain is moot. What matters is what he has revealed about the state of our networked world.

- I don’t think there’s much mileage either in demonising the security agencies. They’re doing a job that’s been specified for them by their political masters. There are, of course, always grounds for being suspicious of secretive agencies, and there’s plenty of evidence of past wrongdoing in MI5/6, the CIA, the FBI and our own dear Metropolitan Police (and maybe also the NSA, though I’m not up to speed on its history in that regard). Maybe there are rogue elements loose in their contemporary manifestations, but what Snowden has revealed is so systemic and large-scale as to relegate individual malfeasance to the status of noise in the signal. The buck we are dealing with at the moment stops with the politicians: the missions they have tasked the agencies with carrying out, the laws they have made and the ‘oversight’ mechanisms they have devised and are now operating. (That’s not to say that the agencies are blameless, by the way, or that they don’t play a hidden role in lawmaking. I’m sure that, for example, the UK Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act owed quite a lot to internal lobbying by GCHQ and MI5. But in terms of the post-Snowden fallout, that’s a secondary issue just at the moment.)

- The official protestations that if Snowden had been a serious whistleblower then he should have confided his concerns to his superiors is laughable cant. Does anybody seriously believe that we would be having the debates we’re having if Snowden hadn’t done what he’s done? In this context, the experience of William Binney is key. He saw what was happening (ie that the NSA was spying on American citizens using the tools that he had designed) and resigned from the Agency. Nothing happened. Nothing.

Having got that stuff out of he way, where are we now?

My colleague David Runciman makes a useful distinction between scandals and crises. Scandals happen all the time in democracies; they generate violent controversies, lots of media coverage and maybe public discussion. But they pass and nothing much changes. Normal life resumes. Crises, on the other hand, do eventually lead to significant reform or change. When the British phone-hacking story broke, many of us felt that it was a genuine crisis that would lead to significant change in the way the tabloid newspapers behaved. But now it looks as though it was just a scandal, because nothing significant will have changed, despite the Leveson Inquiry and its aftermath. The newspaper industry will continue to ‘regulate’ itself, and the newspapers will continue to behave badly.

The big question about the surveillance controversy, therefore, is whether it is a scandal or a crisis. And my reading of events to date is not encouraging: it will turn out to have been a scandal, not a crisis, because I can see no evidence that the relevant governments have any intention of changing their practices. That’s not to say that there haven’t been flurries of activity. Obama set up his famous Intelligence Review Panel of five wise men (all of them insiders, of course), and they duly produced a 300-page report with its 46 recommendations for consideration by the administration. But a close reading of Obama’s recent speech and the resulting Presidential Policy Directive suggests that nothing fundamental is going the change.

As Benjamin Wittes of the Brookings Institution puts it,

“In his speech Obama squarely aligns himself with the intelligence community’s own central narrative of recent events: Its activities are essential, the president says; its activities are lawful and non-abusive (mistakes notwithstanding); and the community’s critics will hold it accountable for failures to connect the dots just as breezily as they now hold it accountable for the use of available tools to connect those dots.

That said, Obama goes on, we need changes. But Obama is careful to describe the reasons we need changes. It’s not to rein in an out of control intelligence community. It’s because “for our intelligence community to be effective over the long haul, we must maintain the trust of the American people, and people around the world.”

What that means is that the US will unapologetically continue its bulk collection and other programmes; continue to ignore the privacy rights of non-Americans; and so on. The mood music is different, of course; lip-service is paid to the need to be respectful of others, etc. But in the end, the national security of the United States trumps everything.

It will be the same story in Britain. The Intelligence Services Committee has launched an investigation, the results of which are not yet available. My hunch is that while there will be more soothing mood music, along the lines essayed by the Chairman of the Committee, Sir Malcolm Rifkind, in his recent Wadham Lecture at Oxford which concluded thus:

True public servants operate with noble motivations, lawful authority, and subject to rigorous oversight. These are the values that distinguish public servants from a public threat. That is how those who work for our intelligence agencies see themselves. That is how most of the public see them. That has been my own experience seeing them at work over a number of years. It is in all our interests that that should remain their justified reputation in the Internet Age.

In practice, therefore, there will be no substantial change. We will continue to have ‘oversight theatre’ rather than rigorous democratic accountability. And I expect that the Foreign Secretary will continue to intone his if-you-have-nothing-to-hide-then-you-have-nothing-to-fear mantra. And all this will be tolerated because the Great British Public appears to be largely relaxed about the whole business.

The only developments that might transform it from a scandal into a crisis are (a) possible action by the EU or by some European governments (notably Germany); (b) really vigorous pushback by the American Internet giants who are concerned about the long-term damage that the Snowden revelations is inflicting on their businesses; and (c) intensive technological resistance by engineering and Internet community activists.

On (a), I’ll believe it when I see it. In this respect, when EU governments are confronted with a bleak choice between confronting an implacable United States and doing nothing, most — even Germany — will choose the latter course. On (b) we’re seeing steps like Google offering end-to-end encryption for Gmail users, implementing perfect forward secrecy on communications between its server farms and laying its own intercontinental fibre-optic cables. But the companies are inextricably compromised in all this because they’re all in the same business as the NSA — comprehensive, intensive surveillance. And on (c) we see tech resistance like the IETF’s determination to insert more encryption in the Internet’s internal workings, which is a bit like putting treacle into the NSA’s surveillance machine, vigorous calls to arms by sages like Eben Moglen and renewed calls to citizens to use TOR and other protective technologies.

All good stuff, which I hope will have beneficial effects. But without political change — which will only happen if, in the end, there is widespread and palpable public concern and outrage — these reactions will have only limited impact. One of the mistakes that we techno-utopians made was to assume that technology would eventually trump politics. I remember thinking that when PGP first appeared in the early 1990s. At last the average citizen could have the same privacy from government (and other snooping) that the state had hitherto reserved for itself. And then along came the aforementioned RIPA in 2000 with its provision that a duly-authorised agent of the Home Secretary (aka Minister of the Interior) could demand that one hand over one’s encryption keys or face a gaol sentence of two years. For most people, caving in would be a no-brainer. And suddenly technology didn’t look so omnipotent after all.

So a bleak — but I fear realistic — conclusion is that the national surveillance state is here to stay. Our democracies seem unwilling, or unable, to choose a different path. If that’s true, then we need to start thinking about what lies ahead. What we’re likely to see is the emergence of a bi-polar world in which there are two competing surveillance empires: one run by the US and its allies, the other run by the Chinese. Think of it as Apple’s IoS and Google’s Android. In those circumstances, the stuff that Ross Anderson has been writing recently suddenly seems very apposite. In a surveillance ‘market’, Ross asks, why shouldn’t the network effects that dominate commercial competition in information markets come into play? “The Snowden papers”, he writes,

reveal that the modern world of signals intelligence exhibits strong network effects which cause surveillance platforms to behave much like operating systems or social networks. So while India used to be happy to buy warplanes from Russia (and they still do), they now share intelligence with the NSA as it has the bigger network. Networks also tend to merge, so we see the convergence of intelligence with law enforcement everywhere, from PRISM to the UK Communications Data Bill.

There is an interesting cultural split in that while the IT industry understands network effects extremely well, the international relations community pays almost no attention to it. So it’s not just a matter of the left coast thinking Snowden a whistleblower and the right coast thinking him a traitor; there is a real gap in the underlying conceptual analysis.

That is a shame. The global surveillance network that’s currently being built by the NSA, GCHQ and its collaborator agencies in dozens of countries may become a new international institution, like the World Bank or the United Nations, but more influential and rather harder to govern. And just as Britain’s imperial network of telegraph and telephone cables survived the demise of empire, so the global surveillance network may survive America’s pre-eminence. Mr Obama might care to stop and wonder whether the amount of privacy he extends to a farmer in the Punjab today might be correlated with what amount of privacy the ruler of China will extend to his grandchildren in fifty years’ time. What goes around, comes around.

It sure does.

How to explain Net Neutrality

A case study in how to communicate a complex idea.

Thanks to Tom for spotting it.

Quote of the day

“Calling a developer a coder is like a tourist calling San Francisco Frisco.

It’s one sure way to tell they’re a tourist.”

When Scottish eyes are smiling

The most fascinating thing in UK politics at the moment is the upcoming Scottish Referendum. It takes place on September 18, a date that is inexorably approaching. If the Scots were to vote for independence, then the consequences would be profound. For one thing, it would signal the end of the British Labour party as a potential governing party in the remaining rump of the “United Kingdom” because so many Labour MPs come from Scottish constituencies. It would also condemn the rump, at least in the short to medium term, to permanent Tory government. There are also tricky questions like whether an independent Scotland would be able to join the EU; what would happen to the UK’s only nuclear submarine base (which is located in Faslane, in Scotland); who “owns’ the remaining reserves of North Sea oil and gas; and so on.

In thinking about what would have to happen after a “Yes” vote, people have been scratching their heads for a precedent. (The Russian annexation of Crimea doesn’t count.) The nearest thing we have is what happened when Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Settling the outstanding issues then took five years and 10,000 separate negotiations.

For a long time the governing elite in Westminster assumed that the Scots would never be so foolish as to make the break, and so paid little attention to the awful prospect of an independent Scotland. But as the dreadful moment approaches, a certain amount of panic has set in. Most people (including me) think that, in the end, the Scots will balk at the prospect of going it alone. But it’s not a sure thing any more, and every time David Cameron goes to Scotland he swells the ranks of the ‘Yes” party. (The Tories have only a single MP in all of Scotland.)

Most intriguing of all, however, is the dilemma posed by the fact that the Scottish Referendum takes place just under a year before the next UK general election. If the Scots vote for Independence, then Scotland will become an independent state on 24 March 2016. So what would happen to (Westminster) MPs elected to represent Scottish constituencies in the UK general election. The SNP’s answer is that they will serve only a 10-month term, which itself is constitutionally dubious. And from the point of view of the rump of the former UK it would be outrageous to have a Parliament which contained 59 representatives elected by what has become a “foreign” country. And so on and so on.

One aspect of the Scottish vote that hasn’t been discussed much in Westminster is the impact that all this is having in Northern Ireland. When I was there a few months ago, signs of acute anxiety in the “Unionist” community were palpable, for very obvious reasons. The whole raison d’etre of Unionism, after all, is attachment to the “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland”. It’s why when you drive through the working-class protestant areas of Belfast you see gable walls and t adorned with murals of the “Union Jack”. It’s why there were violent riots every night for weeks on end when a decision was made by Belfast City Council not to fly the Union Jack from the City Hall on every day of the year.

So any threat to the unity of this United Kingdom poses an existential threat for the protestants of Northern Ireland, many of whom are descended from Scottish settlers who made their way across the Irish sea when the island of Ireland was a badly-governed British colony. So you can imagine their dismay when many of their compatriots in Scotland have apparently come to the conclusion that their treasured Union isn’t worth having.

Mostly this aspect of the Referendum seems to have escaped the attention of the British media. Not the eagle eye of the New York Times, though. In yesterday’s International edition, the paper’s London correspondent, Katrin Bennhold, had an interesting dispatch from Belfast, where she had been sampling opinion in the protestant community. She starts by reminding readers that “As early as 2012, the former leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, Tom Elliott, described the Scottish National Party as ‘a greater threat to the union than the violence of the I.R.A.'” She cites a warning by Ian Paisley Jr of the Democratic Unionist Party that if Scotland voted for independence, it could embolden dissident republicans and kindle new violence in Northern Ireland, and quotes Reg Empey, another prominent Unionist politician saying that “Northern Ireland could end up like West Pakistan with a foreign country [an independent Scotland] on one side of us and a foreign country [the Irish Republic] on the other side of us”.

And then, of course, there is the disturbing thought that, whatever happens on September 18, Britain might vote in its own referendum after the next election, to leave the EU. This would have the effect of transforming the “soft border” that currently separates Northern Ireland from the Republic into a “hard frontier” between the UK and the EU. And that could also have potentially explosive effects, given that the current porosity of the border (which I benefit from every time I visit my family) eases tensions on both sides.

Interesting times, eh?

Yay! Gmail to get end-to-end encryption

This has been a long time coming — properly encrypted Gmail — but it’s very welcome. Here’s the relevant extract from the Google security blog:

Today, we’re adding to that list the alpha version of a new tool. It’s called End-to-End and it’s a Chrome extension intended for users who need additional security beyond what we already provide.

“End-to-end” encryption means data leaving your browser will be encrypted until the message’s intended recipient decrypts it, and that similarly encrypted messages sent to you will remain that way until you decrypt them in your browser.

While end-to-end encryption tools like PGP and GnuPG have been around for a long time, they require a great deal of technical know-how and manual effort to use. To help make this kind of encryption a bit easier, we’re releasing code for a new Chrome extension that uses OpenPGP, an open standard supported by many existing encryption tools.

However, you won’t find the End-to-End extension in the Chrome Web Store quite yet; we’re just sharing the code today so that the community can test and evaluate it, helping us make sure that it’s as secure as it needs to be before people start relying on it. (And we mean it: our Vulnerability Reward Program offers financial awards for finding security bugs in Google code, including End-to-End.)

Once we feel that the extension is ready for primetime, we’ll make it available in the Chrome Web Store, and anyone will be able to use it to send and receive end-to-end encrypted emails through their existing web-based email provider.

We recognize that this sort of encryption will probably only be used for very sensitive messages or by those who need added protection. But we hope that the End-to-End extension will make it quicker and easier for people to get that extra layer of security should they need it.