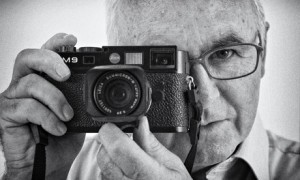

Norfolk, August 2014.

The Leica phenomenon

Photograph by Antonio Olmos for the Observer.

My Observer essay marking the centenary of the Leica camera.

I’m a photographer. No, let me rephrase that: I would like to be a photographer. In reality I’m merely an obsessive who takes lots of photographs in the hope that some day, just once, he will produce an image that is really, truly memorable. Like the images that Henri Cartier-Bresson captured, apparently effortlessly, in their thousands. Think, for example, of his famous picture of the guy leaping over a puddle; or the one of the two stout couples enjoying a picnic on the banks of the Marne; or his magical picture of a cheeky young boy carrying two bottles of red wine on the Rue Mouffetard in 1954. I like this last one particularly, because the lad in the photograph is about the same age as I was then and I often wonder if he’s still around, and what he looks like now.

You can think about this obsessiveness, this quest for the one perfect picture, as a kind of illness. If so, then I’ve had it for more than half a century. And I’m not the only sufferer…

Closure

Web services are ‘free’, which is why we’re all in chains

This morning’s Observer column.

‘Be careful what you wish for,” runs the adage. “You might just get it.” In the case of the internet, or, at any rate, the world wide web, this is exactly what happened. We wanted exciting services – email, blogging, social networking, image hosting – that were “free”. And we got them. What we also got, but hadn’t bargained for, was deep, intensive and persistent surveillance of everything we do online.

We ought to have known that it would happen. There’s no such thing as a free lunch, after all…

Shorts

The boardwalk

TOR, Taylor Swift and breaking the Kafkaesque spiral

Photo cc https://secure.flickr.com/photos/comedynose/7865159650

Ever since the Snowden revelations began I’ve been arguing that Kafka is as good a guide to our surveillance crisis as is Orwell. The reason: one of the triggers that prompts the spooks to take an interest in someone is if that person is using serious tools to protect their privacy. It’s like painting a target on your back.

So if you use PGP to encrypt your email, or TOR for anonymous browsing, then you are likely to be seen as someone who warrants more detailed surveillance. After all, if you’ve nothing to hide… etc.

And there’s no way you would know that you had been selected for special treatment. This sounds like a situation that Kafka would recognise.

Until the other day, I couldn’t think of a way out of this vicious cycle. And then I came on reports (e.g. here) that a musician of whom I’d never heard — electronic music artist Aphex Twin — had announced the details of his new album on a site only accessible through Tor.

This resulted in the page attracting 133,000 views in little over 24 hours. This is within the limits of what TOR can currently handle, but Tor’s executive director, Andrew Lewman, worries that a more mainstream artist could break the system in its current state.

“If tomorrow, Taylor Swift said ‘to all my hundreds of millions of fans, go to this [Tor] address’, it would not work well. We’re into the millions now, and we have a few companies saying ‘we want to put Tor as a privacy mode in our premier products, can you handle the scale of 75-100m devices of users’, and right now the answer is no, we can’t. Not daily.”

This sounds like — and is — a problem. But it’s also an opportunity. Because what we need is for encrypted email and anonymous browsing to become the norm so that the spooks can’t argue that only evil people would resort to using such tools.

And here’s where Aphix Twin and Taylor Swift come in. They have the power to kickstart the mainstreaming of TOR — to make it normal. Of course for that to be effective it means that TOR has to be boosted and expanded and securely funded. Just as the big Internet companies have finally realised that they have to chip in and support, for example, the OpenSSL project, so they should now chip in to help build the infrastructure that would enable TOR to become the default was we all did web browsing.