Some people think that it does

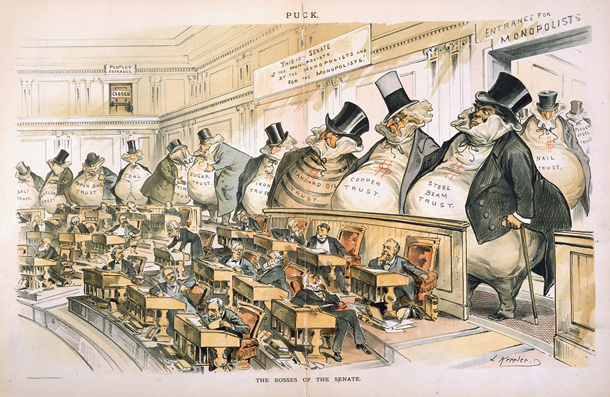

Most cyberattacks to date—by China, Russia, Iran, Syria, North Korea, Israel, the United States, and a dozen or so other nations, as well as scads of gangsters and simple mischief-makers—have been mounted in order to steal money, patents, credit card numbers, or national-security secrets. Whoever hacked Sony (probably a North Korean agency or contractor) did so to put pressure on free speech—in effect, to alter American popular culture and suppress constitutional rights.

Matt Devost, president and CEO of FusionX LLC, one of the leading computer-security firms dotting the Washington suburbs, told me in an email this morning, “This is the dawn of a new age. No longer do you have to worry just about the theft of money or intellectual property, but also about attacks that are designed to be as destructive as possible—and to influence your behavior.”

Bob Gourley, co-founder and partner of Cognito, another such firm, agrees. “I have tracked cyber threats since December 1998 and have never seen anything like this. It might have roots in the early Web-defacements for propaganda”—usually by anti-war or animal-rights groups—“but they were child’s play, done really for bragging rights. A new line has been crossed here.”

And the attack has had effects. Sony has canceled the film’s scheduled release due to terrorist threats against theaters (even though no evidence links the source of the threats to the source of the hacking). While a Seth Rogen comedy is an unlikely cause for a protest of principle, a case can be made that Sony’s submission to political pressure—especially pressure from a foreign source, especially if that source is Kim Jong-un—should be protested.

Well, it might be seen as an attack on American popular culture, I suppose.

Apparently some (off-the-record-natch) US sources think that Kim Jong Un and his chaps are responsible. In which case it’s an instance of cyberwarfare, not just an anti-corporate stunt.

And, as @dangillmor asks, “Are these the same US govt people who determined that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction?”

Kim Zetter has a good, sceptical piece in Wired.

What it all adds up to is that the big difference between “cyberwar” and the kinetic version is that it’s very hard to be sure who has just attacked you.

And, as usual, Dave Winer has an original take on it:

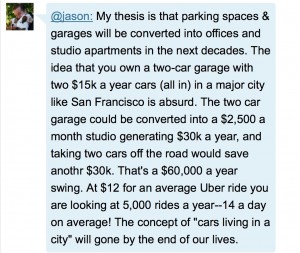

Back in 2000 when Napster was raging, I kept writing blog posts asking this basic question. Isn’t there some way the music industry can make billions of dollars off the new excitement in music?#

Turns out there was. Ask all the streaming music services that have been born since the huge war that the music industry had with the Internet. Was it necessary? Would they have done better if they had embraced the inevitable change instead of trying to hold it back? The answer is always, yes, it seems.#

Well, now it seems Sony is doing it again, on behalf of the movie industry. Going to war with the Internet. Only now in 2014, the Internet is no longer a novel plaything, it’s the underpinning of our civilization, and that includes the entertainment industry. But all they see is the evil side of the net. They don’t get the idea that all their customers are now on the net. Yeah there might be a few holdouts here and there, but not many. #

What if instead of going to war, they tried to work with the good that’s on the Internet? It has shown over and over it responds. People basically want a way to feel good about themselves. To do good. To make the world better. To not feel powerless. It’s perverted perhaps to think that Hollywood which is so averse to change, could try to use this goodwill to make money, but I think they could, if they appealed to our imaginations instead of fear.#