The Public House

The OED says that “pub” is an abbreviation of ‘Public House’ or inn. This legendary institution has been around since 1754, so it was likely to have been called a ‘public house’ for quite a while. (The dictionary dates the abbreviation only from the mid-19th century.)

Quote of the Day

“Democracy has at least one merit, namely that a Member of Parliament cannot be stupider than his constituents, for the more stupid he is, the more stupid they were to elect him.”

- Bertrand Russell

I kept thinking about this quote as the ‘Honeytrap’ scandal unfolded in Westminster.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Keith Richards | I’m Waiting For The Man (Lou Reed Cover)

Wonderful!

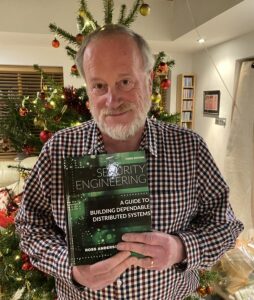

Long Read of the Day

The Apocalyptic Systems Thriller as a non-fiction genre

Henry Farrell is one of the most perceptive observers of the times we’re living in. This essay is just the latest in a thoughtstream of distinctive commentary. It was sparked, he says, by a piece in the New York Times by the novelist Hari Kunzru on a fictional genre he (Kunzru) calls the “apocalyptic systems thriller” (think Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for The Future (which I highly recommend, btw).

“Just as Kunzru describes the influence of non-fiction on a new genre of fiction”, Henry writes,

that genre is re-shaping non-fiction, and should, in my opinion, be shaping it a lot more. We live in an enormously, terrifyingly complex world. We need new narrative techniques to make sense of it, and even more importantly to begin to articulate ways in which human beings can collectively respond to it. Furthermore, non-fiction writers ought steal liberally from fiction writers, just as fiction writers have stolen from the futurists and scenario planners that Kunzru describes. Rather than emphasizing the one-way passage from non-fiction to fiction, we should think of fiction and non-fiction as intertwined like twin helices, generating and regenerating new possibilities. The great advantage of thinking this way (at least from my selfish point of view) is that it focuses our attention on how to improve narrative technique in non-fiction too…

Do read the whole thing. It’s worth it.

Julian Assange

Good piece by Rupa Subramanya in The Free Press.

Some argue Assange is an anarchist, trying to undermine our nation. Others say he is a heroic activist, fighting for a transparent democracy.

But the truth, actually, lies somewhere in the middle: yes, Assange is a deeply flawed character, and he also does not deserve to spend the rest of his life behind bars. Today, President Biden said he is considering a plea from Assange’s homeland of Australia to drop the case, which is a welcome development. Because if the hacker is convicted, it’s not only journalism that will be weaker—it’s democracy itself.

Democracy depends on whistleblowers. We need people like Chelsea Manning. Or Edward Snowden, the former National Security Agency employee who leaked documents in 2013 that revealed a disturbing level of government surveillance. Or Thomas Drake, a high-ranking NSA official who blew the whistle on 9/11 intelligence failures. Or Jamie Reed, a case manager at a gender clinic for children, who revealed in these pages that doctors there too hastily prescribed hormones to young adults with mental health issues.

If politicians truly respect the First Amendment, they must defend the freedom of whistleblowers and investigative journalists to deliver the truth to the public—however ugly it may be…

Yep.

My commonplace booklet

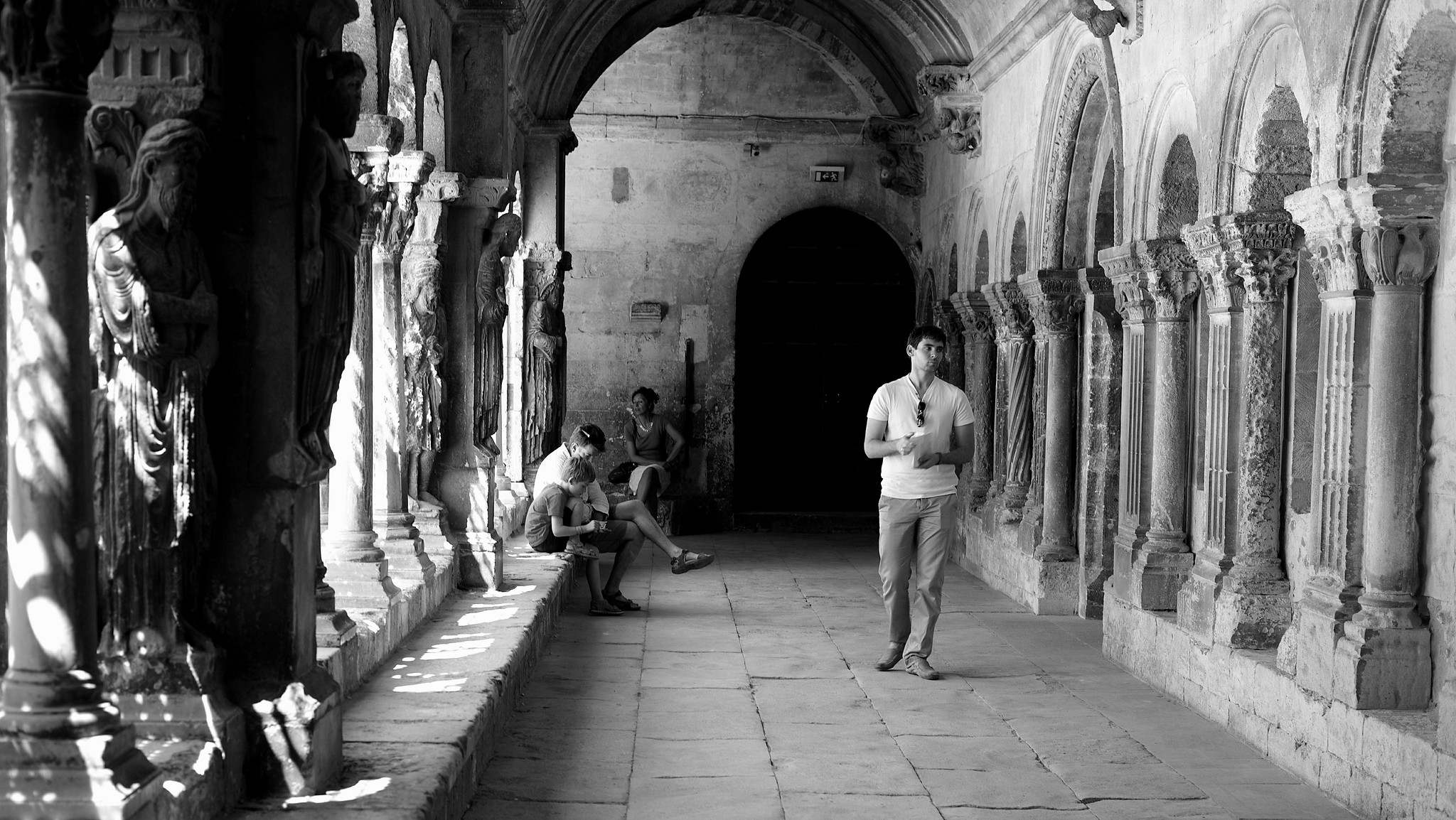

On the naming of plants

A fragment from a nice essay in the New Yorker by Yiyun Li:

“Lotus” comes from the Greek lōtos, a mythical plant bringing forgetfulness to those who eat its fruits. (I have eaten my share of lotus seeds, a delicacy in Chinese cuisine, without achieving oblivion.) “Fuchsia,” a word I often misspelled as “fuschia”—what mythical story accompanies thee? It turns out that fuchsia was named for the sixteenth-century German physician and botanist Leonhard Fuchs, whose name gave birth not only to that of the flower and that of the color but also to the nickname, Fuchsienstadt, for his home town of Wemding, where there is a pyramid made of as many as seven hundred fuchsia plants. And yet Fuchs never saw the flower fuchsia in his lifetime: it was discovered in the Caribbean and named by the French botanist and monk Charles Plumier, who was born a hundred and forty-five years after Fuchs. What led Plumier to name the flower for Fuchs? One can ask the question, but any speculation would be closer to fiction, just as peony was once the physician of the gods and lotus would bring forgetfulness.

I love fuchsia, largely I guess because I spent part of my childhood in Kerry, where it grows in fabulous abundance — so much so that you can drive on small rural roads where the hedges on either side seems to be entirely made up of fuchsia. And, like Li, it took me years to realise that it’s not spelled ‘fuschia’!

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!