Knitgear

Seen in a lovely knitting shop in Riga.

Quote of the Day

”It’s like the world’s worst advent calendar. Every day we open the door and there’s another crisis.”

- Unnamed Tory MP talking to the Financial Times, 17 December, 2021

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Chuck Berry With Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band | Johnny B. Goode

If this isn’t fabulous, then I don’t know what is.

Long Read of the Day

Can Big Tech Serve Democracy?

A terrific review essay in the Boston Review by Henry Farrell and Glen Weyl, about technology and the fate of democracy. Sobering, very well-informed and beautifully written. Can I say more?

Re-using computer code has its downsides

Yesterday’s Observer column:

In one of those delicious coincidences that warm the cockles of every tech columnist’s heart, in the same week that the entire internet community was scrambling to patch a glaring vulnerability that affects countless millions of web servers across the world, the UK government announced a grand new National Cyber Security Strategy that, even if actually implemented, would have been largely irrelevant to the crisis at hand.

Initially, it looked like a prank in the amazingly popular Minecraft game. If someone inserted an apparently meaningless string of characters into a conversation in the game’s chat, it would have the effect of taking over the server on which it was running and download some malware that could then have the capacity to do all kinds of nefarious things. Since Minecraft (now owned by Microsoft) is the best-selling video game of all time (more than 238m copies sold and 140 million monthly active users), this vulnerability was obviously worrying, but hey, it’s only a video game…

This slightly comforting thought was exploded on 9 December by a tweet from Chen Zhaojun of Alibaba’s Cloud Security Team.…

LATER This is huge problem and the computing world is nowhere near getting on top of it yet, as this sobering assessment points out.

Johnson’s slow-motion disintegration

Being Prime Minister of the UK is a pretty demanding job. One can see its effect etched in the rapid ageing faces of those who have held the post. And we can already see this in the current incumbent, who obviously didn’t realise that the job included doing some actual work. Here are two photographs of him from a few days ago, one from Sky News, the other from the BBC which make the point:

But the really interesting evidence of his disintegration came last week in his big speech to the Confederation of British Industry — the bosses’ trade union — in which he suddenly started raving about the Peppa Pig theme park as a sign of British creativity. It’s almost cruel to watch it, but — Hey! — it’s Christmas. Give it a go. Here’s the link.

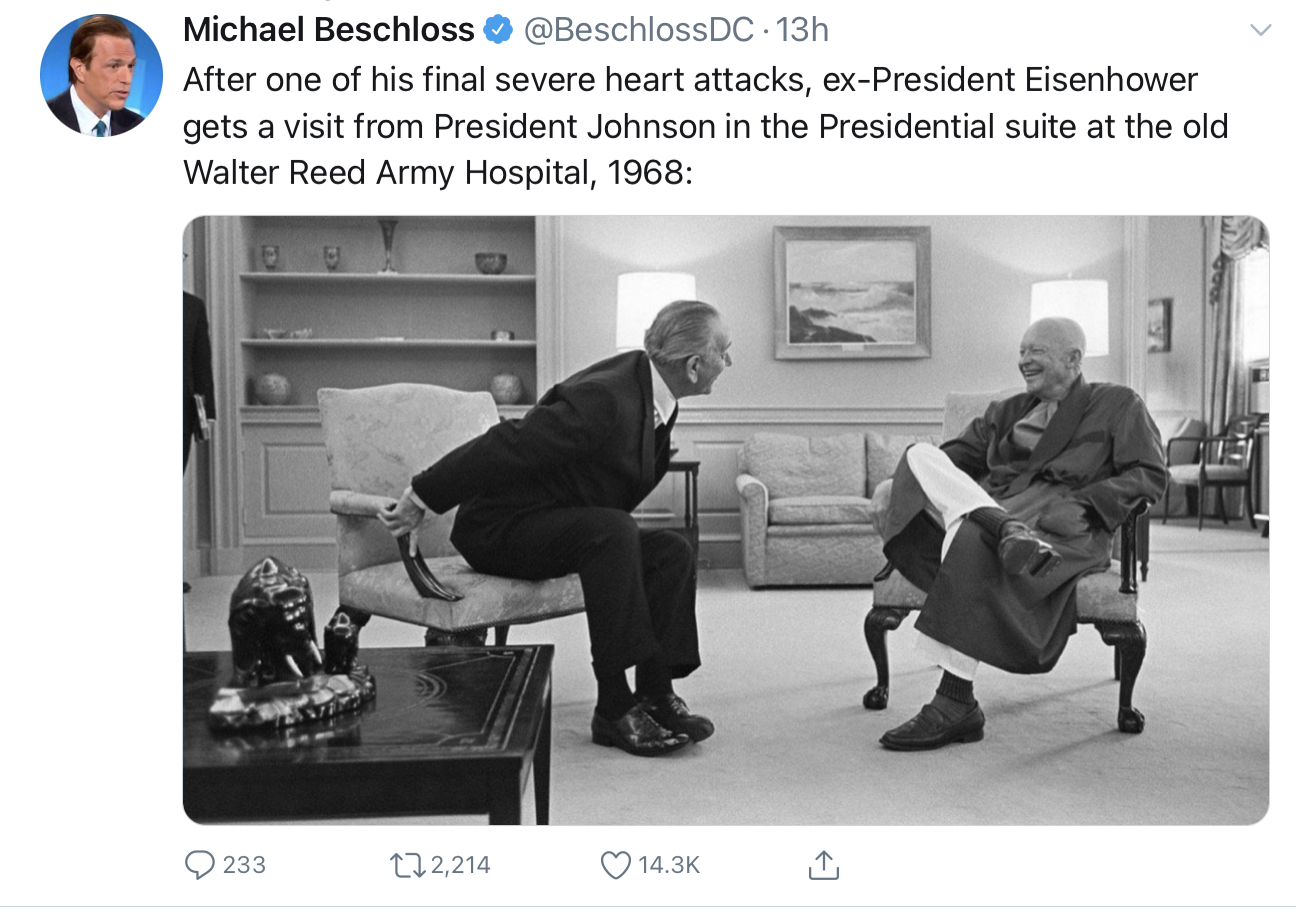

Has Francis Fukuyama lost the plot?

Sounds like an impertinent question but I’ve been re-reading Louis Menand’s demolition job on Francis Fukuyama’s attempt to use identity as the new general theory of everything. Here’s the nub of Menand’s critique:

Twenty-nine years later, it seems that the realists haven’t gone anywhere, and that history has a few more tricks up its sleeve. It turns out that liberal democracy and free trade may actually be rather fragile achievements. (Consumerism appears safe for now.) There is something out there that doesn’t like liberalism, and is making trouble for the survival of its institutions.

Fukuyama thinks he knows what that something is, and his answer is summed up in the title of his new book, “Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). The demand for recognition, Fukuyama says, is the “master concept” that explains all the contemporary dissatisfactions with the global liberal order: Vladimir Putin, Osama bin Laden, Xi Jinping, Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, gay marriage, isis, Brexit, resurgent European nationalisms, anti-immigration political movements, campus identity politics, and the election of Donald Trump. It also explains the Protestant Reformation, the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, Chinese Communism, the civil-rights movement, the women’s movement, multiculturalism, and the thought of Luther, Rousseau, Kant, Nietzsche, Freud, and Simone de Beauvoir. Oh, and the whole business begins with Plato’s Republic. Fukuyama covers all of this in less than two hundred pages. How does he do it?

Not well. Some of the problem comes from misunderstanding figures like Beauvoir and Freud; some comes from reducing the work of complex writers like Rousseau and Nietzsche to a single philosophical bullet point. A lot comes from the astonishingly blasé assumption—which was also the astonishingly blasé assumption of “The End of History?”—that Western thought is universal thought. But the whole project, trying to fit Vladimir Putin into the same analytic paradigm as Black Lives Matter and tracing them both back to Martin Luther, is far-fetched. It’s a case of Great Booksism: history as a chain of paper dolls cut out of books that only a tiny fraction of human beings have even heard of. Fukuyama is a smart man, but no one could have made this argument work.

My hunch is this book was a mistake. I say this as someone who has loved some of Fukuyama’s earlier work. I remember being blown away by the original ‘End of history?’ essay, for example, maybe because of the excitement of the 1989 Zeitgeist and discontinuities in my personal life at the time. And I learned a lot from those two seminal books of his on the quest for order and its subsequent decay. I’m also impressed by the fact that he’s a good photographer and a bit of a geek — as one can see from the server-rack that is his home-computing setup. I like people who can straddle the two cultures.

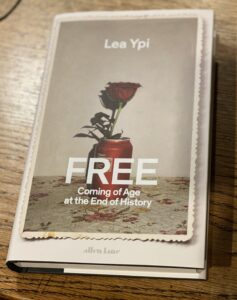

Christmas Books – 2

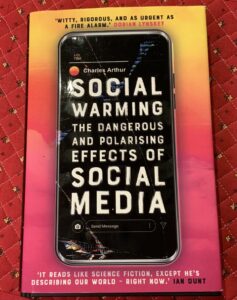

Charles Arthur’s Social Warming: The dangerous and polarising effects of social media is the best book I’ve seen on the global impact of the business model that fuels Facebook, Google, Twitter & Co. The implicit metaphor in the title — that the way social media superheats the public sphere on which democracy depends mirrors the way that burning fossil fuels warms the biosphere — provides a brilliant way of thinking about the industry.

As someone who follows, and writes about, tech I often forget that there’s a lot of history and background that I take for granted — and then I run into non-tech-savvy people and realise they have no idea about how social-media feeds are algorithmically curated, say, or why many people in the global South are unaware that Facebook is not the Internet. But then I think: how could they have known? After all, mainstream media doesn’t do a good job of explaining it. And social-media definitely have no incentive to do it. Now, instead of having to do impromptu explanations, I can just point them to Charles’s book — which is why I can’t wait for the paperback version to come out.

My commonplace booklet

Alec Guinness has always been one of my favourite actors. This clip from an interview he did with Michael Parkinson might explain why.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!