Vanishing point

An EV year

We picked up our Tesla 12 months ago today. Before that we’d had a series of Toyota Prius hybrids, which were terrific, ultra-reliable cars, so this was our first fully electric vehicle. It’s been an interesting experience.

Some reflections on the year.

-

The biggest disadvantage of owning a Tesla is that people immediately hold one responsible for Elon Musk, the founder of the company, who is three-parts genius and one part fruitcake.

-

It was ironic having a new car without being able to go anywhere serious in it! So in the first year we were able to go on only three longish trips. And because we cycle to work, we haven’t used it to commute. That’s lockdown for you.

-

It’s lovely to drive — and I say that as someone who has been a serious petrolhead in my time. In the 1970s I had a 3.8-litre Mk 2 Jaguar, for example, when that was a pretty serious indulgence. (The Yom Kippur war in 1973 and the consequent quadrupling of the oil price ended that particular love-affair.) The Tesla Model 3 is as agile, responsive and sure-footed as any of the fancy ICE cars I’ve driven in my time. And it’s fast — as quick as even conventional Porsche 911s: zero to 60 in 3.1 seconds. Not that you’d ever want to do that in real life.

-

It has all-wheel drive and good traction control, which turned out to be very useful driving through snowstorms in Yorkshire just over a week ago.

-

Two ways of looking at it.

1: it’s basically software with wheels. Regular software updates (at near-weekly intervals) just like an iPhone. Mostly they bring bug fixes or minor changes. But sometimes big changes are software driven — for example the acceleration boost that our model has came via software, not through mechanics with spanners.

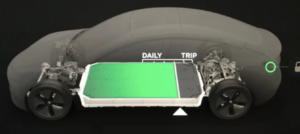

2: It’s really just a big skateboard with wheels at the four corners. The board is the battery.

-

If you’re lucky enough to have a driveway and are therefore able to install a home-charger then ‘range anxiety’ mostly fades away. That’s no consolation to urbanites, though.

-

From talking to other EV owners, I get the feeling that once you’ve owned an electric vehicle you’ll never want to go back to ICE. (And of course eventually you won’t have that option anyway, so perhaps it makes sense to jump before you’re pushed.)

Quote of the Day

””When one burns one’s bridges, what a very nice fire it makes”

- Dylan Thomas

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Ry Cooder & David Lindley | The Promised Land | April1994 | Fillmore Auditorium

Wonderful!

Long Read of the Day

Why Humans Aren’t the Worst (Despite, Well, Everything Happening in the World) The journalist and historian Rutger Bregman makes a case for the “collective brilliance” of humanity.

Transcript of a podcast interview with Kara Swisher.

I can never figure Bregman out. Occasionally he reminds me of the Monty Python guys singing “Always look on the bright side of life”. At other times he seems good at seeing through conventional wisdom that’s actually baloney. This interview with Kara Swisher is good largely because she keeps probing him. Here’s a sample segment:

Swisher: So one of the things we’ve been talking about is self-interest. And I want you to address the downright brutality in human history. We have to talk, obviously, about the Holocaust. It’s hard to look at that and think humans are decent. Why doesn’t this disprove your argument?

Bregman: What I wanted to do at first was to show that veneer theory, this notion that we are evil or we do evil things because we are evil, is way too simplistic or just basically wrong. But then you’re still left with the question, why do we engage in warfare and ethnic cleansing and all these kinds of horrible things? So the honest answer is that you have to start building up a very layered explanation with a lot of different ingredients. I look at the role of German soldiers during the Second World War. In 1944 and 1945, many Allied psychologists couldn’t understand why these soldiers were still fighting at the end of the war, when it was clear they were going to lose. And they assumed at first that these soldiers must be brainwashed or something like that, must be highly fanatical Nazis. But it turns out that actually what was driving them most of the time was Kameradschaft, comradeship, loyalty for their friends. And the German Army Command, they knew this. So they deliberately tried to keep friends together as much as possible during the course of the war, because they knew then they would be much more effective fighters. Now, I’m not saying this to — how do you say that — condone anything. I’m just trying to use it as an explanation.

Anyway, it makes for a good read.

How TikTok keeps people hooked

With a billion users, TikTok is now the most successful smartphone app in the world.

The NYT’s Ben Smith has seen a document describing the algorithmic approach that keeps TikTokers hooked.

The document explains frankly that in the pursuit of the company’s “ultimate goal” of adding daily active users, it has chosen to optimize for two closely related metrics in the stream of videos it serves: “retention” — that is, whether a user comes back — and “time spent.” The app wants to keep you there as long as possible. The experience is sometimes described as an addiction, though it also recalls a frequent criticism of pop culture. The playwright David Mamet, writing scornfully in 1998 about “pseudoart,” observed that “people are drawn to summer movies because they are not satisfying, and so they offer opportunities to repeat the compulsion.”

“This system means that watch time is key. The algorithm tries to get people addicted rather than giving them what they really want,” said Guillaume Chaslot, the founder of Algo Transparency, a group based in Paris that has studied YouTube’s recommendation system and takes a dark view of the effect of the product on children, in particular. Mr. Chaslot reviewed the TikTok document at my request.

According to Smith the formula the apple recommendation engine runs on is:

Plike x Vlike + Pcomment x Vcomment + Eplaytime x Vplaytime + Pplay x Vplay

Which implies that a prediction driven by machine learning and actual user behaviour are summed up for each of three bits of data: likes, comments and playtime, as well as an indication that the video has been played.

Interesting but not necessarily a scoop. I bet the formula that drives YouTube’s recommendation algorithm is rather similar.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!