Fabulous essay by Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen, uncovering the politics and biases embedded in the guge image databases that have been used for training machine learning software. Here’s how it begins:

You open up a database of pictures used to train artificial intelligence systems. At first, things seem straightforward. You’re met with thousands of images: apples and oranges, birds, dogs, horses, mountains, clouds, houses, and street signs. But as you probe further into the dataset, people begin to appear: cheerleaders, scuba divers, welders, Boy Scouts, fire walkers, and flower girls. Things get strange: A photograph of a woman smiling in a bikini is labeled a “slattern, slut, slovenly woman, trollop.” A young man drinking beer is categorized as an “alcoholic, alky, dipsomaniac, boozer, lush, soaker, souse.” A child wearing sunglasses is classified as a “failure, loser, non-starter, unsuccessful person.” You’re looking at the “person” category in a dataset called ImageNet, one of the most widely used training sets for machine learning.

Something is wrong with this picture.

Where did these images come from? Why were the people in the photos labeled this way? What sorts of politics are at work when pictures are paired with labels, and what are the implications when they are used to train technical systems?

In short, how did we get here?

The authors begin with a deceptively simple question: What work do images do in AI systems? What are computers meant to recognize in an image and what is misrecognised or even completely invisible? They examine the methods used for introducing images into computer systems and look at “how taxonomies order the foundational concepts that will become intelligible to a computer system”. Then they turn to the question of labeling: “how do humans tell computers which words will relate to a given image? And what is at stake in the way AI systems use these labels to classify humans, including by race, gender, emotions, ability, sexuality, and personality?” And finally, they turn to examine the purposes that computer vision is meant to serve in our society and interrogate the judgments, choices, and consequences of providing computers with these capacities.

This is a really insightful and sobering essay, based on extensive research.

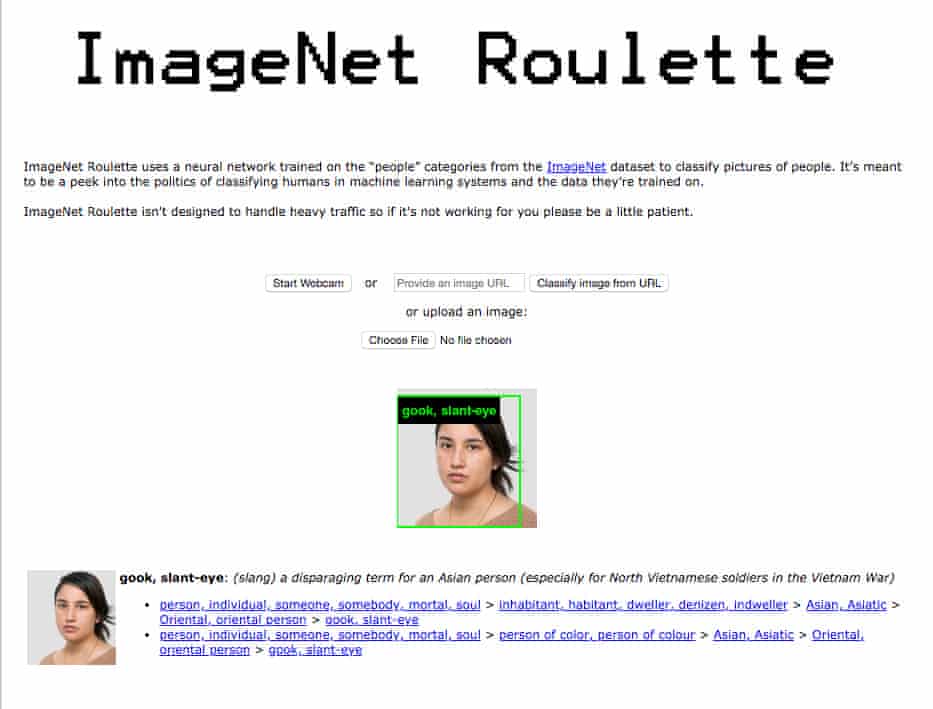

Some time ago Crawford and Paglen created an experimental website — ImageNet Roulette — which enabled anyone to upload their photograph and then pulled up from the ImageNet database how the person would be classified based on their photograph. The site is now offline, but the Guardian journalist Julia Carrie Wong wrote an interesting article about it recently in the course of which she investigated how it would classify/describe her from her Guardian byline photo. Here’s what she found.

Interesting ne c’est pas? Remember, this is the technology underpinning facial recognition.

Do read the whole thing.