It’s hard to believe but Apple has 800 people working just on the iPhone camera. Every so often, we get a glimpse of what they are doing. Basically, they’re using computation to enhance what can be obtained from a pretty small sensor. One sees this in the way HDR (High Dynamic Range) seems to be built-in to every iPhone X photograph. And now we’re seeing it in the way the camera can produce the kind of convincing bokeh(the blur produced in the out-of-focus parts of an image produced by a lens) that could hitherto only be got from particular kinds of optical lenses at wide apertures.

Matthew Panzarino, who is a professional photographer, has a useful review of the new iPhone XS in which he comments on this:

Unwilling to settle for a templatized bokeh that felt good and leave it that, the camera team went the extra mile and created an algorithmic model that contains virtual ‘characteristics’ of the iPhone XS’s lens. Just as a photographer might pick one lens or another for a particular effect, the camera team built out the bokeh model after testing a multitude of lenses from all of the classic camera systems.

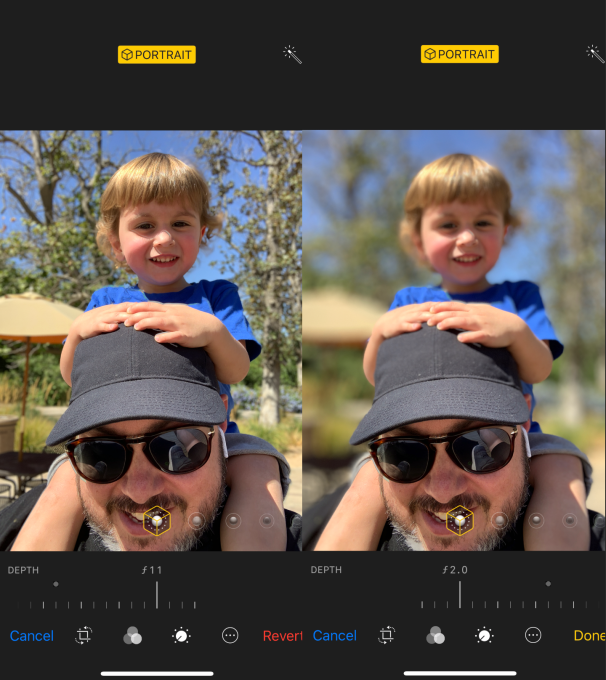

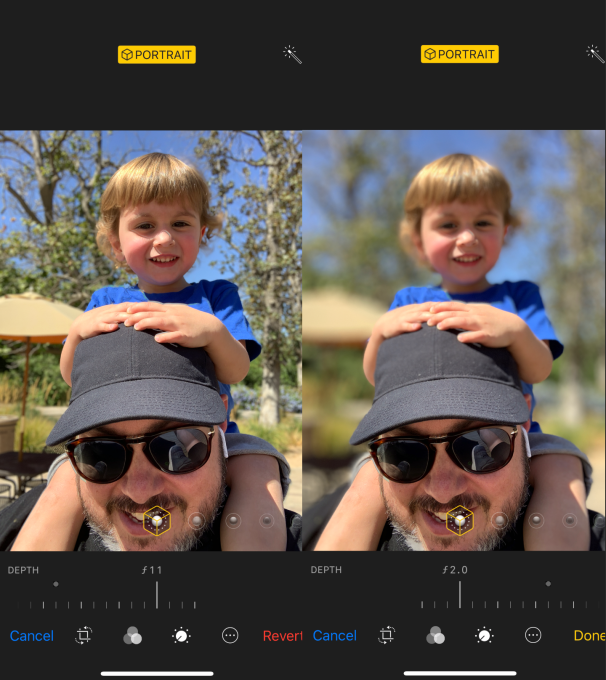

Really striking, though, is an example Panzarino uses of how a post-hoc adjustable depth of focus can be really useful. He shows a photograph of himself with his young son perched on his shoulders.

And an adjustable depth of focus isn’t just good for blurring, it’s also good for un-blurring. This portrait mode selfie placed my son in the blurry zone because it focused on my face. Sure, I could turn the portrait mode off on an iPhone X and get everything sharp, but now I can choose to “add” him to the in-focus area while still leaving the background blurry. Super cool feature I think is going to get a lot of use.

Yep. Once, photography was all about optics. From now on it’ll increasingly be about computation.