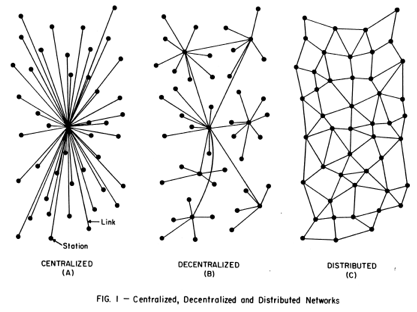

There’s a useful piece on the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s site about federated networking, seen as a way of counteracting the centralising power of outfits like Facebook.

To understand how federated social networking would be an improvement, we should understand how online social networking essentially works today. Right now, when you sign up for Facebook, you get a Facebook profile, which is a collection of data about you that lives on Facebook's servers. You can add words and pictures to your Facebook profile, and your Facebook profile can have a variety of relationships — it can be friends with other Facebook profiles, it can be a ‘fan’ of another Facebook page, or ‘like’ a web page containing a Facebook widget. Crucially, if you want to interact meaningfully with anyone else’s Facebook profile or any application offered on the Facebook platform, you have to sign up with Facebook and conduct your online social networking on Facebook’s servers, and according to Facebook’s rules and preferences. (You can replace “Facebook” with “Orkut,” “LinkedIn,” “Twitter,” and essentially tell the same story.)

We’ve all watched the dark side of this arrangement unfold, building a sad catalog of the consequences of turning over data to a social networking company. The social networking company might cause you to overshare information that you don’t want shared, or might disclose your information to advertisers or the government, harming your privacy. And conversely, the company may force you to undershare by deleting your profile, or censoring information that you want to see make it out into the world, ultimately curbing your freedom of expression online. And because the company may do this, governments might attempt to require them to do it, sometimes even without asking or informing the end-user.

How does it work?

To join a federated social network, you’ll be able to choose from an array of “profile providers,” just like you can choose an email provider. You will even be able to set up your own server and provide your social networking profile yourself. And in a federated social network, any profile can talk to another profile — even if it’s on a different server.

Imagine the Web as an open sea. To use Facebook, you have to immigrate to Facebook Island and get a Facebook House, in a land with a single ruler. But the distributed social networks being developed now will allow you to choose from many islands, connected to one another by bridges, and you can even have the option of building your own island and your own bridges.

Why is this important?

Why does this matter?

The beauty of the Internet so far is that its greatest ideas tend to put as much control as possible in the hands of individual users. And online social networking is a powerful tool for the many who want a service that compiles all the digital stuff shared by family, friends, and colleagues. But so far, social networking has grown in a way that concentrates control over that information — status posts, photos, and even your relationships themselves — with individual companies.

Distributed social networks represent a model that can plausibly return control and choice to the hands of the Internet user. If this seems mundane, consider that informed citizens worldwide are using online social networking tools to share vital information about how to improve their communities and their governments — and that in some places, the consequences if you’re discovered to be doing so are arrest, torture, or imprisonment. With more user control, diversity, and innovation, individuals speaking out under oppressive governments could conduct activism on social networking sites while also having a choice of services and providers that may be better equipped to protect their security and anonymity.