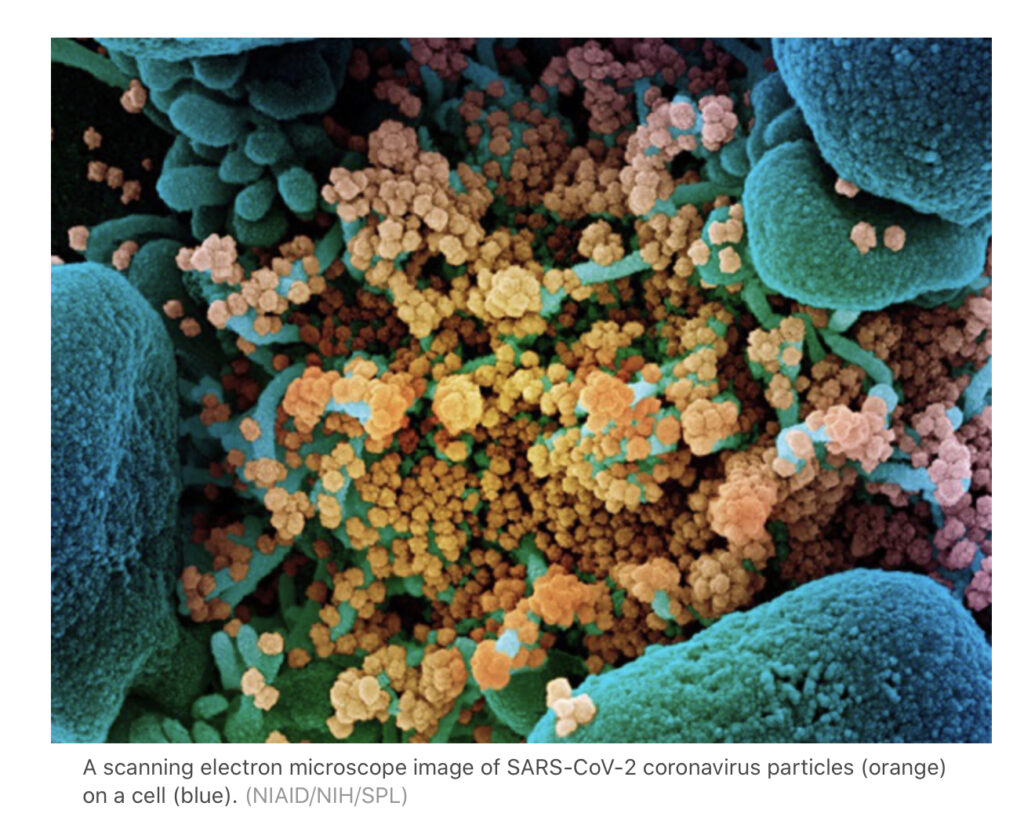

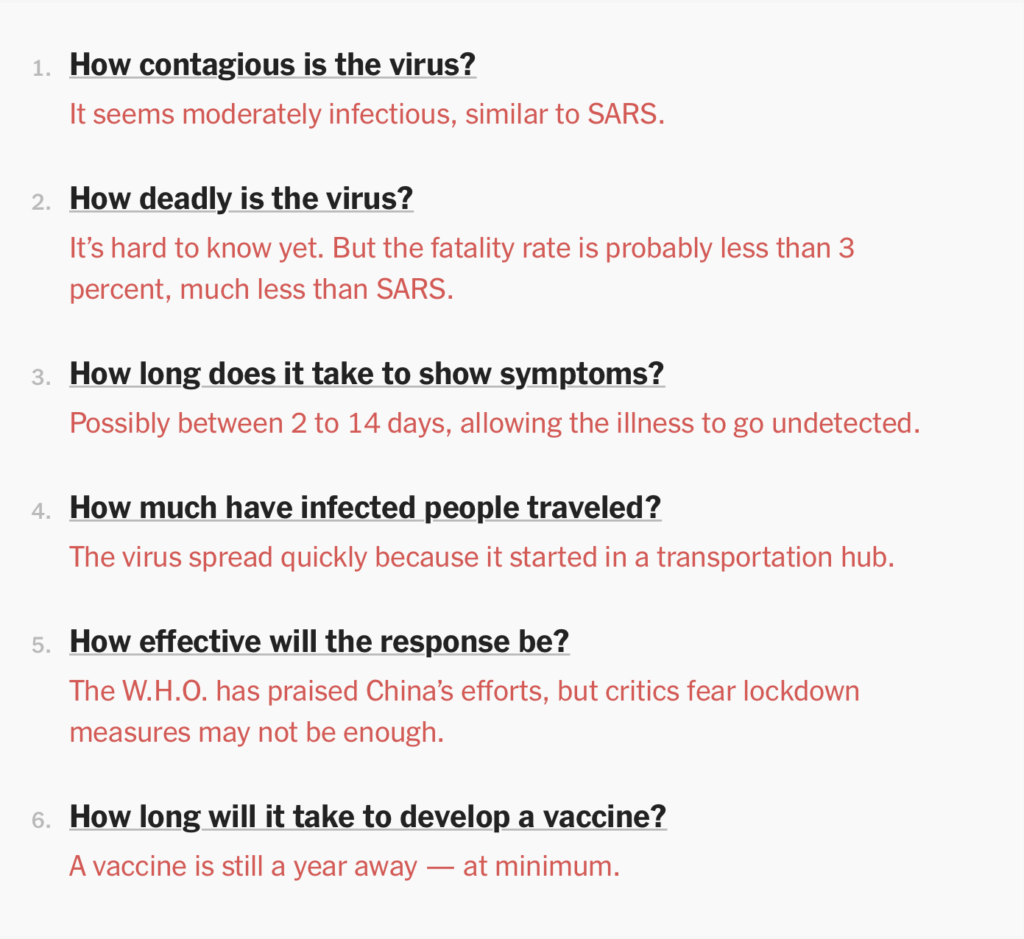

Meet the enemy

From Nature.

Monochromatic vision

Once upon a time every photograph I took was in black and white. Colour film was just too expensive. But as an experiment during lockdown, I decided to go back to monochrome — and was reminded that B&W photography is a completely different art form. Colour is easier — much easier.

Here’s one picture from yesterday’s foray.

Click on the image to see a larger size.

Trump, Twitter, Facebook and the future of online speech

Terrific, wide-ranging, historically-informed New Yorker essay by Anna Wiener on Section 230 and related matters.

Still, there’s a reason the order focussed on Section 230. The law is considered foundational to Silicon Valley. In “The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet,” a “biography” of the legislation, Jeff Kosseff, a professor of cybersecurity law at the U.S. Naval Academy, writes that “it is impossible to divorce the success of the U.S. technology sector from the significant benefits of Section 230.” Meanwhile, despite being an exceptionally short piece of text, the law has been a source of debate and confusion for nearly twenty-five years. Since the 2016 Presidential election, as awareness of Silicon Valley’s largely unregulated power has grown, it has come under intensified scrutiny and attack from both major political parties. “All the people in power have fallen out of love with Section 230,” Goldman told me, in a phone call. “I think Section 230 is doomed.” The law is a point of vulnerability for an industry that appears invulnerable. If it changes, the Internet does, too.

Great piece. Well worth reading in full if you’re interested in Internet regulation.

It’s mourning in America

The Lincoln Project is a political movement by Republicans who oppose Trump and are trying to persuade fellow-Republicans to drop him. They’re putting together some hard-hitting TV campaign ads. This is the one I like best, because it deliberately echoes Ronald Reagan’s famous “Morning in America” slogan.

A future shaped by the coronavirus

Quartz asked dozens of experts for their best predictions on how the world will be different in five years.

Here’s Hany Farid’s answer. He’s a professor at the University of California, Berkeley with appointments in both Electrical Engineering & Computer Science and the School of Information. He specializes in the analysis of digital images, particularly deepfakes.

In five years, I expect us to have long since reached the boiling point that leads to reining in an almost entirely unregulated technology sector to contend with how technology has been weaponized against individuals, society, and democracy. Social media in particular has become the primary source of news for more than half of people around the world. At the same time, social media is littered with hate, divisiveness, misinformation, and illegal activity. The global Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the breadth and depth of these issues as people around the world are spending more time online alongside deadly misinformation, outrageous conspiracies, and small- to large-scale fraud. The reckoning that is sure to come will change the way we view and interact with the technology we have grown more and more reliant on in our lives.

Yep.

Tim Berners-Lee is optimistic, as ever. He chose to imagine looking back from 2025:

It’s 2025 and now the world is working again. You want me to compare my life now with 2020? Well, 2020 was ghastly in so many ways. The pandemic was awful, and the way the world worked was so dysfunctional.

Today it’s quite different. I feel that I am part of functional communities and societies at different levels, and I feel that within those groups, I am part of the solutions we are finding to the problems. I have sources of news and information that I trust, and I play a part in making them trustworthy. Importantly, I feel that most other people in the world, while they have different priorities and different ideas of how the economy should run, are working off the same facts, the same science.

Thinking about my life—be it day-to-day family life, my work, my music, my play, my volunteering with organizations—it’s all, in fact, data. It is data I control. It all connects together. What I love now is how everything is online as data: I feel powerful. I can see things from all of my life together. I can share anything with anyone. People share all kinds of things with me. When I decide what to do on Friday, I see in my calendar all the things happening in each of the segments of my life all brought together. How else would I function? When I wonder about doing something, I see its cost in dollars, in time, and in carbon, whether it is at home or at work, and I feel I can make decisions with a sort of integrity I didn’t have in 2020.

I’m proud of the world managing to make communal decisions after the crisis of 2020. I’m proud we stopped using paper. I’m proud of the oil we left in the ground. I’m proud of the privacy we have given back to people who opened up their health, medical, and genetic data in the pandemics of 2020 and 2022. I’m happy that people are in control of that data and were in a position to offer it up. I am proud of the people I know who worked to make all the apps I use talk the same language. We take it for granted now that you and I can use entirely different apps or tools for looking, sharing, and managing data—no matter whether that’s for photos, banking info, or other projects. It wasn’t always like that!

We call that interoperability or interop. I teach my kids about interop. The interop movement was born out of a project from MIT called Solid, a company called Inrupt, and an open-source community. Together, they set about updating the web of 2020 by flipping the rules of who gets value from data. It was a lot of hard work to get here.

My digital life is my world; it is my identity. I use all kinds of devices to live my digital life, of course. I think of them as different windows into the same world. But it’s not about the devices. It’s not about the apps. It’s the huge benefit of linking all the data—not just my data, but also the data shared with me, connected device data, and all the publicly available data—all in one world. That’s the essence of my life and the main change for me since 2020, I think. Since you asked.

Like I said, ever the optimist.

If you’re over 75, getting Covid is like playing Russian roulette

Interesting piece by Antonio Regalado,the Biomedicine Editor of MIT’s Tech Review:

By now you might be wondering what your own death risk is. Online, you can find apps that will calculate it, like one at covid19survivalcalculator.com, which employs odds ratios from the World Health Organization. I gave it my age, gender, body mass index, and underlying conditions and learned that my overall death risk was a bit higher than the average. But the site also wanted to account for my chance of getting infected in the first place. After I told it I was social distancing and mostly wearing a mask, and my rural zip code, the gadget thought I had only a 5% of getting infected.

I clicked, the page paused, and the final answer appeared: “Survival Probability: 99.975%”.

Those are odds I can live with. And that’s why I am not leaving the house.

Moral: Keep your distance, stay at home as much as you can and wear a mask. It’s not rocket science.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!