One of the most unsettling experiences of the last decade has been watching Western democracies sleepwalking into a national security nightmare. Each incremental step towards total surveillance follows the same script. It goes like this: first, a new security ‘threat’ is uncovered, revealed or hypothesised; then a technical ‘solution’ to the new threat is proposed, trialled (sometimes) and then implemented — usually at formidable cost to the public; finally, the new ‘solution’ proves inadequate. But instead of investigating whether it might have been misguided in the first place, a new, even more intrusive, ‘solution’ is proposed and implemented.

In this way we went from verbal questioning to pat-down searches at airports, and thence to x-ray scanning of cabin-baggage, to having to submit laptops to separate scanning (including, I gather, examination of hard-disk files in some cases), to having to take off our shoes, to having all cosmetic fluids (including toothpaste) inspected, and — most recently — to back-scatter x-ray scanning which reveals the shape of passengers’ breasts and genitals. It may be that we will get to the point where only passengers willing to stip naked are allowed to board a plane. The result: a mode of travel that was sometimes pleasant and usually convenient has been transformed into a deeply time-consuming, stressful and unpleasant ordeal

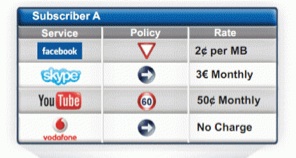

The rationale in all cases is the same; these measures are necessary to thwart a threat that is self-evidently awful and in that sense the measures are for the public good. We are all agreed, are we not, that suicidal terrorism is a bad things and so any measure deemed necessary to prevent it must be good? Likewise, we all agree that street crime and disorder is an evil, so CCTV cameras must be a good thing, mustn’t they? So we now have countries like Britain where no resident of an urban area is ever out of sight of a camera. And of course we all abhor child pornography and paedophilia, so we couldn’t possibly object to the Web filtering and packet-sniffing needed to detect and block it, right? A similar argument is used in relation to file-sharing and copyright infringement: this is asserted to be ‘theft’ and since we’re all against theft then any legislative measures forced on ISPs to ‘stop theft’ must be justified. And so on.

So each security initiative has a local justification which is held to be self-evidently obvious. But the aggregate of all these localised ‘solutions’ has a terrifying direction of travel — towards a total surveillance society, a real national security state. And anyone who expresses reservations or objections is invariably rebuffed with the trope that people who have nothing to hide have nothing to fear from these measures.

In the UK, a novel variation on this philosophy has just surfaced in Conservative (capital C) political circles. A right-wing Tory MP who is obsessed with the threat of Internet pornography has been touting the idea that broadband customers who do not want their ISPs to block access to pornography sites should have to register that fact with the ISP. (This is to ‘protect’ children, of course, in case the poor dears should mistype a search term and see images of unspeakable acts in progress.) Last Sunday a British newspaper reported that the communications minister, Ed Vaizey, is concerned about the availability of pornography and says he would quite like ISPs to do something about it for him. According to The Register, “he plans to call the major players to a meeting next month to discuss measures, including the potential for filters that would require those who do want XXX material to opt their connection out”.

The Register doesn’t take this terribly seriously, because it’s convinced that Vaizey is too shrewd to get dragged into the filtering mess that afflicted the Australian government. Maybe he is, but suppose he finds himself unable to hold back the tide of backbench wrath towards the evil Internet, with its WikiLeaks and porn and all. The implicit logic of the approach would fit neatly with everything we’ve seen so far. First of all, the objective is self-evidently ‘good’ — to protect children from pornography. Secondly, we’re not being illiberal — if you want to allow porn all you have to do is to register that fact with your ISP. What could be fairer than that?

But then consider the direction of travel. What if some future government decides that children should not be exposed to, say, the political propaganda of the British National Party? After all, they’re a nasty pack of xenophobic racists. And then there are the animal rights activists — nasty fanatics who put superglue in butchers’ shop doors on Christmas eve. Why should thay enjoy “the oxygen of publicity”? And then there are… Well, you get the point.

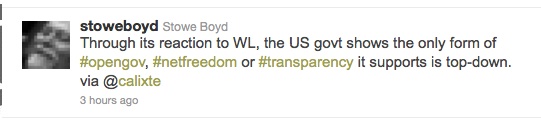

Stowe Boyd has an interesting post about another bright security wheeze which has really sinister long-term implications. Since terrrists and drug barons use cash, why not do away with the stuff and switch over to electronic money instead?

In a cashless economy, insurgents’ and terrorists’ electronic payments would generate audit trails that could be screened by data mining software; every payment and transfer would yield a treasure trove of information about their agents, their locations and their intentions. This would pose similar challenges for criminals.

Who would such a system benefit, asks Boyd?

Not the part-time sex worker, trying to make ends meet in a down economy. Not the bellman at the airport, whose tips might disappear after the transition to cards. Not the homeless guy I gave $2 to the other day, or the busker playing guitar in the train station. Or the Green Peace folks collecting coins at the park.

The ones that benefit are the those selling the cards and the readers. And the policy-makers who want to see the flow of cash to find — supposedly — drug lords and terrorists, but secretly want to know everything about everybody.

But this is the argument for pervasive surveillance again. In the name of security and safety, they say we should all accept the intrusion of the government into our private lives so that the state can be protected from its enemies. After all, they say, if we aren’t doing anything illegal, why should we care? What have we got to hide?

But we have the right to privacy in our doings. We don’t have to say why we want privacy: it is our right.

And the shadowy doings at the margins of people’s lives are exactly the point of privacy. The man funneling money to a child born to his mistress without his wife’s knowledge, or a woman loaning money to her brother without her husband knowing: they want anonymous cash.

Boyd thinks that cash is a prerequisite of a free society, and he’s right.

“Cash”, he says,

is not a metaphor for freedom, it is a requirement of freedom. A strong society that accepts human nature without moralizing will always have anonymous cash. Only totalitarian governments — where everything not expressly required is illegal — would want to monitor the flow of every cent.

.