Lots of Observer readers have been writing to the Readers’ Editor (and emailing me directly) castigating me for claiming in my essay that Robert Capa’s D-Day Landing pictures were shot using a Leica camera. They maintain — as does Wikipedia — that he was using a Contax II rangefinder on the day, so I’m clearly in error on that point.

There is more disagreement about whether Capa’s famous Spanish Civil War photographs were shot with a Leica. There’s a photograph of him from the time carrying a movie camera with a stills camera in a leather case hanging round his neck. Not being an expert on camera cases, I don’t know whether it’s a Leica case or a Contax one. I guess Capa himself, a guy who covered five major wars, would have regarded this controversy as trivial. But it’s the kind of detail that we obsessives obsess about!

I wish I’d taken the trouble to check the D-Day assertion, but I guess because Capa had been one of the founder-members of Magnum I lazily assumed he had also been a Leica user. Myths endure because nobody checks. Mea culpa.

The same is true for the myths about Dorothy Parker, who is famous for being a world-class wisecracker. In an aside in the piece I claimed that she had reviewed Christopher Isherwood’s I Am A Camera with the crack “Me No Leica”. But, as many readers pointed out, the credit belongs elsewhere — with the theatre critic Walter Kerr. One of his most famous reviews was his three word summary of John Van Druten’s I Am A Camera in 1951: ‘Me no Leica.’

Parker has an enviable trove of wisecracks attributed to her, and she was an exceedingly funny (and exceedingly sad) lady. But in at least one other case she gets more credit than she deserves. When Robert Benchley came to her and said “Calvin Coolidge is dead”, she famously replied, “How could they tell?”, and this has gone down in history as an example of her wit. What’s not so well known, however, is that Benchley replied “He had an erection”, but this was deemed too scandalous for polite society at the time and so Parker’s punchline was the one that endured. Benchley’s widow allegedly went to her deathbed infuriated by the fact that her husband hadn’t got the credit he was due for that exchange.

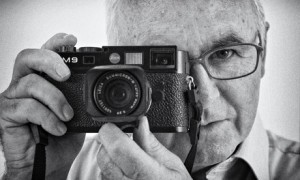

Still, Eric Clapton hasn’t written in (yet) to say that he does sometimes remember to take the lens cap off his M8. And nobody from the Royal Household has been in touch to say that Her Majesty has, on occasion, forgotten to remove the cap on her M3.