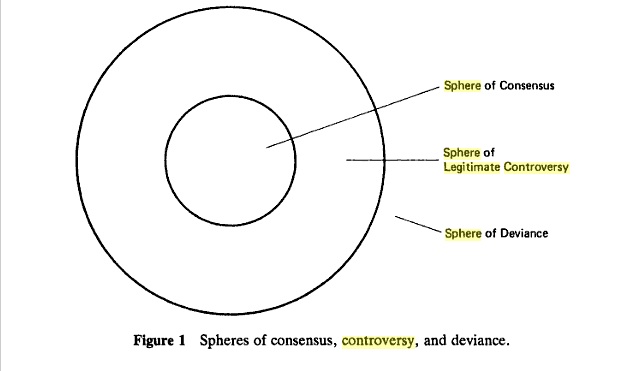

This diagram (from The Uncensored War, Daniel Hallin’s book about the media and the Vietnam war) is the heart of a terrific essay by Jay Rosen on journalism’s role in stifling public discussion while pretending to enhance it. Sample:

1.) The sphere of legitimate debate is the one journalists recognize as real, normal, everyday terrain. They think of their work as taking place almost exclusively within this space. (It doesn’t, but they think so.) Hallin: “This is the region of electoral contests and legislative debates, of issues recognized as such by the major established actors of the American political process.”

Here the two-party system reigns, and the news agenda is what the people in power are likely to have on their agenda. Perhaps the purest expression of this sphere is Washington Week on PBS, where journalists discuss what the two-party system defines as “the issues.” Objectivity and balance are “the supreme journalistic virtues” for the panelists on Washington Week because when there is legitimate debate it’s hard to know where the truth lies. There are risks in saying that truth lies with one faction in the debate, as against another— even when it does. He said, she said journalism is like the bad seed of this sphere, but also a logical outcome of it.

2. ) The sphere of consensus is the “motherhood and apple pie” of politics, the things on which everyone is thought to agree. Propositions that are seen as uncontroversial to the point of boring, true to the point of self-evident, or so widely-held that they’re almost universal lie within this sphere. Here, Hallin writes, “journalists do not feel compelled either to present opposing views or to remain disinterested observers.” (Which means that anyone whose basic views lie outside the sphere of consensus will experience the press not just as biased but savagely so.)

Consensus in American politics begins, of course, with the United States Constitution, but it includes other propositions too, like “Lincoln was a great president,” and “it doesn’t matter where you come from, you can succeed in America.” Whereas journalists equate ideology with the clash of programs and parties in the debate sphere, academics know that the consensus or background sphere is almost pure ideology: the American creed.

3.) In the sphere of deviance we find “political actors and views which journalists and the political mainstream of society reject as unworthy of being heard.” As in the sphere of consensus, neutrality isn’t the watchword here; journalists maintain order by either keeping the deviant out of the news entirely or identifying it within the news frame as unacceptable, radical, or just plain impossible. The press “plays the role of exposing, condemning, or excluding from the public agenda” the deviant view, says Hallin. It “marks out and defends the limits of acceptable political conduct.”

Anyone whose views lie within the sphere of deviance—as defined by journalists—will experience the press as an opponent in the struggle for recognition. If you don’t think separation of church and state is such a good idea; if you do think a single payer system is the way to go; if you dissent from the “lockstep behavior of both major American political parties when it comes to Israel” (Glenn Greenwald) chances are you will never find your views reflected in the news. It’s not that there’s a one-sided debate; there’s no debate.

As I say, a terrific essay, well worth reading in full. The comments (including Daniel Hallin’s) are also illuminating.