Jonathan Zittrain from the Berkman Center at Harvard gave this riveting lecture at Duke University on March 3. It’s quite long — an hour and a quarter — so you need to allocate some serious time to it, but IMHO it’s worth it. It starts slowly as he lays out an analytical framework that, at first sight, seems to have little to do with libraries, but about 27 minutes in to the presentation he really hits his stride. For anyone interested in the cultural responsibilities of libraries in a digital era, this is eye-opening stuff becasue it gives some concrete examples of cases where libraries will need to assume really serious responsibilities as curators of the digital record, not just in terms of preservation, but also in defence of historical accuracy.

Category Archives: Media ecology

Toward A New Alexandria

Long, thoughtful and wide-ranging article by Lisbet Rausing in The New Republic about the future of academic libraries in a digital environment.

It is clear that if a new Alexandria is to be built, it needs to be built for the long term, with an unwavering commitment to archival preservation and the public good. A true public good itself, it probably needs to be largely governmentally funded. And, while a global and cooperative venture, it needs to be hosted by one organisation that is reputable, long-standing, nonprofit, and exists in a stable jurisdiction. The Library of Congress, the flagship institution of the world’s only surviving Enlightenment republic, comes to mind. There might be other possibilities, such as the New York Public Library, or the British Library, or a consortium of the world’s leading university libraries—UCLA, Harvard, Cambridge University, and so on.

In other words, the question for scholars and gatekeepers is not whether change is coming. It is whether they will be among the change-makers. And if not them, then who? Who else will ensure long-term conservation and search abilities that are compatible across the bibliome and over time? Who else will ensure equality of access? Ultimately, this is not a challenge of technology, finances, or ultimately even laws, difficult though they are. It is a challenge of will and imagination.

Answering that challenge will require some soul-searching: Do we have the generosity to collaborate? Can we build legal, organizational, and financial structures that will preserve and order—but also share and disseminate the learning of the world? Scholars have traditionally gated and protected knowledge, yet also shared and distributed it in libraries, schools, and universities. We have stood for a republic of learning that is wider than the ivory tower, and now is the time to do so again. We must stand up, as the Swedes say, for folkbildningsidealet, that profoundly democratic vision of universal learning and education…

Worth reading in full.

At the end of the day…

The power of politeness

Amazing video. Thanks for BoingBoing for spotting it.

The paradoxical market for news

There’s a strange paradox in the current gloom afflicting news organisations. On the one hand, the journalistic doomsters believe there is no longer a market for what they produce. On the other hand there’s the Pew Internet & American Life Project’s report which seems to suggest that people can’t get enough of it (news, that is).

In the digital era, news has become omnipresent. Americans access it in multiple formats on multiple platforms on myriad devices. The days of loyalty to a particular news organization on a particular piece of technology in a particular form are gone. The overwhelming majority of Americans (92%) use multiple platforms to get news on a typical day, including national TV, local TV, the internet, local newspapers, radio, and national newspapers. Some 46% of Americans say they get news from four to six media platforms on a typical day. Just 7% get their news from a single media platform on a typical day.

The internet is at the center of the story of how people’s relationship to news is changing. Six in ten Americans (59%) get news from a combination of online and offline sources on a typical day, and the internet is now the third most popular news platform, behind local television news and national television news.

The process Americans use to get news is based on foraging and opportunism. They seem to access news when the spirit moves them or they have a chance to check up on headlines. At the same time, gathering the news is not entirely an open-ended exploration for consumers, even online where there are limitless possibilities for exploring news. While online, most people say they use between two and five online news sources and 65% say they do not have a single favorite website for news. Some 21% say they routinely rely on just one site for their news and information.

I suppose that whaat it comes down to is whether there’s a difference between a demand for something and a market for it. Conventional economics would say that where there’s a demand, there’s always a market.

The glossy mag as App

I’ve long thought that publishing on the Web won’t provide a sustainable business model for magazines, for two reasons: (a) the paywall problem; and (b) the fact that the Web can’t provide the ‘immersive’ reading experience that high-end magazines require. (Some interesting research by the Economist suggests that, in may of their markets, subscribers ‘make an appointment’ with themselves to set aside time every week to read the magazine.) One possible inference is that classy publications stand a better chance of flourishing in an online world if they’re Apps rather than sites. Taking this route addresses the paywall problem (Apple collects the dosh via iTunes store); and it may enable designers to create reading experiences that are more immersive than web browsing. This report suggests that Conde Nast, at least, is beginning to think this way too.

Condé Nast’s plans for the iPad tablet computer from Apple are getting firmer.

The first magazines for which it will create iPad versions are Wired, GQ, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker and Glamour, the company plans to announce in an internal memorandum on Monday.

GQ will have a tablet version of its April issue ready. Vanity Fair and Wired will follow with their June issues, and The New Yorker and Glamour will have issues in the summer (the company has not yet determined the exact timing for those).

The company already sells an iPhone application for GQ. That has sold more than 15,000 copies of the January issue and almost 7,000 of the December issue.

Condé Nast plans to test different prices, types of advertising and approaches to digitizing the magazines for several months before wrapping up the experiment in the fall. “We need to know a little bit more about what kind of a product we can make, how consumers will respond to it, what the distribution system will be,” said Thomas J. Wallace, editorial director of Condé Nast.

The magazines were chosen for their range, he said. “They are representative of the company, right? GQ is men. Glamour is women. Vanity Fair is a dual audience. The New Yorker is unique with its periodicity, and therefore it’s also more news- or text-heavy, and it’s a slightly older audience,” Mr. Wallace said. And Wired has already been working on a reader project with Adobe, the software company that provides publishing tools to much of the magazine industry.

Other than Wired, the digital magazines will be developed internally. “We’re taking a two-track approach partly because we want to learn everything that we can,” said Sarah Chubb, president of Condé Nast Digital.

During the test phase, the company will sell the digital magazines through iTunes. Wired will also be available in non-iTunes formats. While that means Condé Nast will not have access to consumer data — a valuable tool for its marketing — Ms. Chubb said there were other ways to get that information.

Of course, the implication that — once again — Apple will be in pole position to profit from the marketing data that comes from iPad APP sales.

The message in the bottle

Posterity here we come!

Wow! The British Library has selected Memex 1.1 as one of the blogs it’s going to archive for posterity. Blush.

DeadHead memories

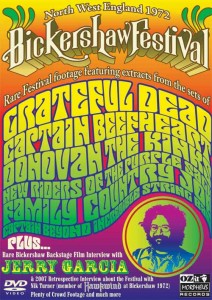

My Observer column on Sunday about the perceptiveness of the Grateful Dead has triggered fond memories in some readers — and stimulated some lovely emails, including this one from a colleague:

In 1972 I was one of the organisers of a big music festival in a place called Bickershaw near Wigan. The Dead were top of the bill and during contract negotiations with them, we were amazed that we had to provide a central area to accommodate anyone who wanted to record their gig. They had realised as early as 1972 that they could give away poor quality recordings, knowing that many would then go out and buy the real thing. I believe they were the largest earners amongst R&R bands for many years. I hung out with Jerry Gracia for a bit and he was very stoned but also very smart.

An interesting footnote – the main festival organiser was one Jeremy Beadle. He wasn’t famous yet but had already started to assume his annoying persona. I think he was the only person at the festival who wasn’t stoned, but he was also very smart and went on to make made lots of money.

There’s a web site for the aforementioned festival too. Gosh! Those were the days.

So is the H.264 problem going to be solved?

Interesting report in The Register about Google’s acquisition of On2, the company that developed the VP3 codec which is the basis for Ogg Theora.

The question is still whether Google will turn around and open source On2’s video codecs. In announcing the original pact, Mountain View made a point of saying that it believes “high-quality video compression technology should be a part of the web platform” — and that On2 is a means of reaching that end.

The major web browser makers – including Google, Apple, Mozilla, Opera, and Microsoft – have failed to agree on a single common codec for the new HTML5 video tag. The HTML5 spec allows for any codec, and while some have opted for the open and license-free Ogg Theora, others are sticking to the license-encumbered H.264 for reasons of performance, hardware support, and alleged patent anxiety.

If you’re new to this, Charles Arthur wrote a helpful piece about it, following on a perceptive piece by Jack Schofield.