Jeff Bezos’s Princeton Commencement Address is the best thing I’ve read today. Sample:

On one particular trip, I was about 10 years old. I was rolling around in the big bench seat in the back of the car. My grandfather was driving. And my grandmother had the passenger seat. She smoked throughout these trips, and I hated the smell.

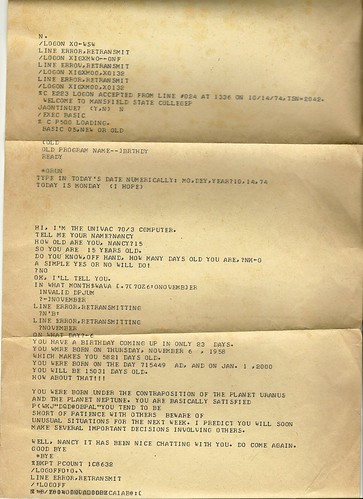

At that age, I'd take any excuse to make estimates and do minor arithmetic. I'd calculate our gas mileage — figure out useless statistics on things like grocery spending. I'd been hearing an ad campaign about smoking. I can't remember the details, but basically the ad said, every puff of a cigarette takes some number of minutes off of your life: I think it might have been two minutes per puff. At any rate, I decided to do the math for my grandmother. I estimated the number of cigarettes per days, estimated the number of puffs per cigarette and so on. When I was satisfied that I'd come up with a reasonable number, I poked my head into the front of the car, tapped my grandmother on the shoulder, and proudly proclaimed, "At two minutes per puff, you've taken nine years off your life!"

I have a vivid memory of what happened, and it was not what I expected. I expected to be applauded for my cleverness and arithmetic skills. "Jeff, you're so smart. You had to have made some tricky estimates, figure out the number of minutes in a year and do some division." That's not what happened. Instead, my grandmother burst into tears. I sat in the backseat and did not know what to do. While my grandmother sat crying, my grandfather, who had been driving in silence, pulled over onto the shoulder of the highway. He got out of the car and came around and opened my door and waited for me to follow. Was I in trouble? My grandfather was a highly intelligent, quiet man. He had never said a harsh word to me, and maybe this was to be the first time? Or maybe he would ask that I get back in the car and apologize to my grandmother. I had no experience in this realm with my grandparents and no way to gauge what the consequences might be. We stopped beside the trailer. My grandfather looked at me, and after a bit of silence, he gently and calmly said, "Jeff, one day you'll understand that it's harder to be kind than clever."

What I want to talk to you about today is the difference between gifts and choices…

In my gloomier moments I sometimes feel that a lifetime spent in universities has left me with the feeling that there’s a high correlation between cleverness and moral cowardice. At any rate, I’ve known some very high-IQ cowards, and rather more modestly-endowed heroes. Who was it who said that anyone with sufficient intelligence can think of a dozen reasons for not doing the right thing?

And I was fortunate to know one extremely intelligent man who was also a genuine hero.