Insightful column about the iPhone phenomenon by Farhad Manjoo: The nub of it is this:

In many fundamental ways, the iPhone breaks the rules of business, especially the rules of the tech business. Those rules have more or less always held that hardware devices keep getting cheaper and less profitable over time. That happens because hardware is easy to commoditize; what seems magical today is widely copied and becomes commonplace tomorrow. It happened in personal computers; it happened in servers; it happened in cameras, music players, and — despite Apple’s best efforts — it may be happening in tablets.

In fact, commoditization has wreaked havoc in the smartphone business — just not for Apple. In the last half-decade, sales of devices running Google’s Android operating system have far surpassed sales of Apple’s devices, and now account for the vast majority of smartphones in use.

For years, observers predicted that Android’s rising market share would in turn lead to lower profits for Apple (profits, not market share, being the point of business). If that had happened, it would have roughly approximated the way the Windows PC industry eclipsed Apple’s Mac business. “Hey, Apple, wake up — it’s happening again,” Henry Blodget, of Business Insider, warned in 2010. And again in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014.

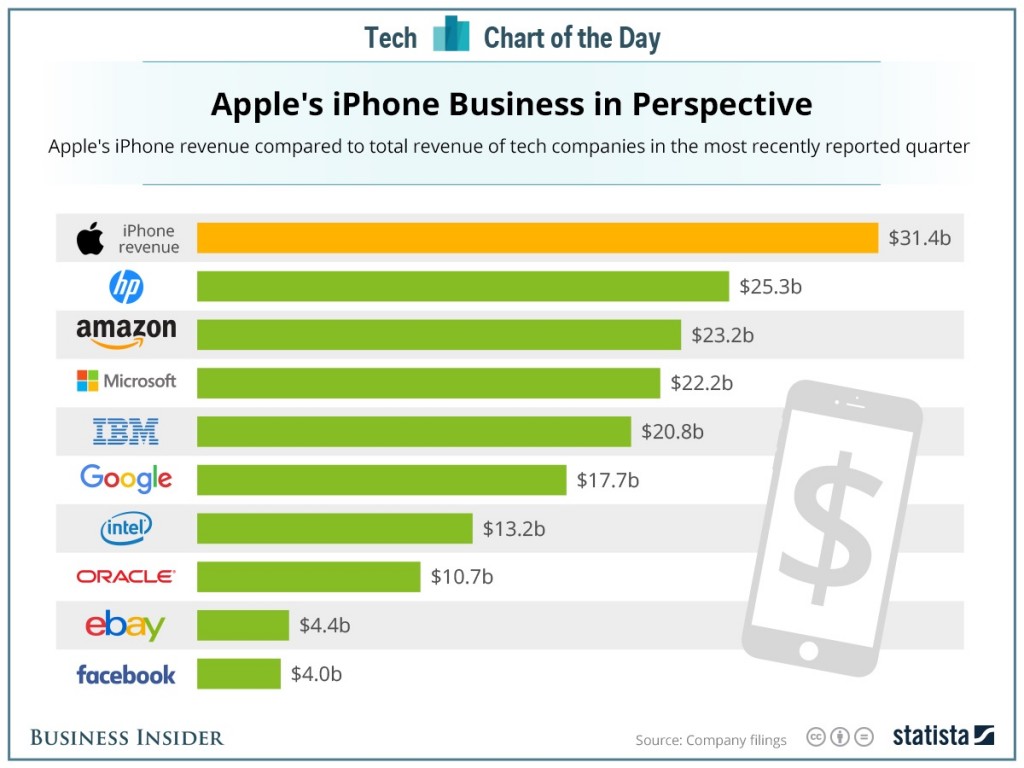

None of those predictions came true. While the iPhone’s sales growth slowed in 2013 and 2014, it rebounded to near-record levels later last year, and its profits have remained lofty.

Instead of killing Apple, commoditization caused something stranger — it hobbled Apple’s main competitor in the smartphone business: Samsung, which until last year was gaining a creeping share of the profits in the smartphone business. At its peak in mid-2013, Samsung was making close to half of every dollar in the smartphone business, according to the research firm Canaccord. (Apple was making the other half.)

But the rise of low-end, pretty great Android phones made by Chinese upstarts like Xiaomi — and the surging popularity of Apple’s large-screen iPhones — put Samsung in a bind. In July, Samsung reported its seventh straight quarter of declining profits.

Yep. The reason why the Apple phone defies the commoditisation rule is that it’s not a standalone device, but part of a highly-functional (and useful) ecosystem. That’s why iPhone users who hanker after, say, Samsung’s or Sony’s latest phone think twice before making the switch: do they really want to leave the comfort and ease of the Apple ecosystem. And Apple has just made joining that ecosystem easier — by releasing an Android App that allegedly makes it simple for Android users to take their data etc. across to their brand new iPhones! Given the amount of money Apple makes from the iPhone, it does now look set to become the world’s first trillion-dollar company.