Ouch!

Tranquillity

We went for a walk today in the RSPB bird sanctuary near Fowlmere. This is the view from one of the hides. It was blissfully peaceful.

Anthropological tales

From Andrew Brown’s Blog…

I happened to be talking to an anthropologist this morning, and the conversation turned to a celebrated academic. “I knew him when I was at New College”, she said. “I was in a lift with him once. There were just the two of us. I was wearing a miniskirt and he put his hand up it.”

“!!??!!” I said: “Did he know you?”“No. Not at all. We hadn’t spoken or anything. He was well known for it. I kicked him, hard, on the shin … I have never ever read any of his books, because of that.”

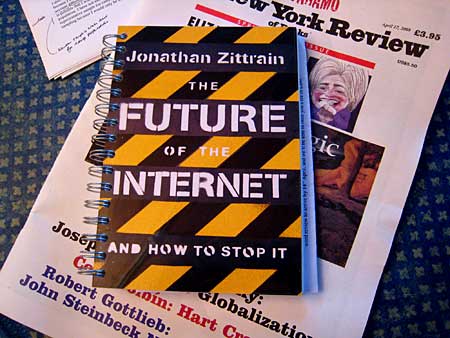

Bedtime reading

Hooray! The proof copy of Jonathan Zittrain’s book has arrived. I’m reviewing it for Management Today. So that’s the weekend taken care of, then.

Sacre Bleu!

Devotees of P.G. Wodehouse will know that whenever a gifted chef ups and leaves there will be hell to pay. Remember what happened when Anatole threatened to leave the employ of Bertie Wooster’s aunt Dahlia?

Well, guess what? Food Gal is reporting that Google’s Executive Chef, Josef Desimone, is jumping ship to become Facebook’s very first executive chef.

This is serious. Mark my words: there will be blood! (To coin a movie title.)

Counting the cost

I thought this kind of stuff only happened in the UK..

The [U.S.] bureau [of the Census] contracted with Harris Corp. in 2006 to pay more about $600 million for a system that included 500,000 handheld devices to be given to census takers in 2010 to gather information from the millions of people who don’t return their mailed forms. The devices were intended to verify all residential addresses in the nation using GPS, collect and transmit the data from the uncounted, and manage the workflow in the field. Unfortunately, in a scenario familiar to most valley engineers, there was a disconnect between contractor and client over the specs. In a test last year in North Carolina, the computer’s interface ended up leaving workers baffled and confused, and initially the units couldn’t transmit the large amounts of data required. At one point, said Commerce Secretary Carlos Gutierrez, the government had some 400 new or clarified technical requirements on its feedback list for Harris. The costs kept climbing, helped along by gross miscalculations. Initially the bureau and Harris agreed that $36 million would cover a help desk for field workers using the handhelds; on further reflection, that figure is now up to $217 million. At a March hearing, Rep. Carolyn Maloney, D-N.Y., said, “What we’re facing is a statistical Katrina on the part of the administration.”

Yesterday came the final blow. Gutierrez told Congress that the whole computer initiative has been called off for the coming census and that the bureau would hire 600,000 temporary workers to do the job with pencil and paper. The expensive handhelds will be used for address verification, but that’s all. She blamed the problem on “a lack of effective communication with one of our key contractors,” while Harris cited the bureau’s ever-shifting specifications. Bottom line, the government will still buy 151,000 of the computers and associated service from Harris, but now the cost has risen to $1.3 billion. That and the related changes will push the cost of the census from what was already a record $11 billion to more than $14 billion. And the census count — with billions in government spending dependent on its accuracy — will still be conducted in crude manual fashion.

The legality of Phorm

From BBC NEWS…

Technical analysis of the Phorm online advertising system has reinforced an expert’s view that it is “illegal”.

The analysis was done by Dr Richard Clayton, a computer security researcher at the University of Cambridge.

What Dr Clayton learned while quizzing Phorm about its system only convinced him that it breaks laws designed to limit unwarranted interception of data…

Richard says, in part:

Phorm assumes that their system “anonymises” and therefore cannot possibly do anyone any harm; they assume that their processing is generic and so it cannot be interception; they assume that their business processes gives them the right to impersonate trusted websites and add tracking cookies under an assumed name; and they assume that if only people understood all the technical details they’d be happy.

Well now’s your chance to see all these technical details for yourself — I have, and I’m still not happy at all.

More here on the BT spokeswoman’s attempt to defend on TV the company’s covert experiment with Phorm.

On this day…

… in 1968, Martin Luther King was shot dead in Memphis, Tennessee. He was 39.

The earliest days of the Web

Fascinating video by Robert Scoble in which Ben Segal, who had been network manager at CERN during Tim Berners-Lee’s time there, talks about the invention of the Web. For all CEOs of large companies, and all Directors of large institutions, there’s a very important message roughly six minutes into the tape.