Raptor and Friend

Quote of the Day

“In baiting a mouse trap with cheese, always leave room for the mouse.”

- ‘Saki’ (H.H. Munro)

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Shaun Davey | The Parting Glass

Davey’s imaginative twist on a beautiful Irish song.

Interestingly, General Martin Dempsey, the 18th Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, sang it on his retirement in September 2015. Which may puzzle some people until they realise that Dempsey is a good old Irish name!

Long Read of the Day

Russia’s got a point: The U.S. broke a NATO promise

Interesting OpEd from May 2016 by Joshua Itzkowitz Shifrinson in the Los Angeles Times.

Moscow solidified its hold on Crimea in April, outlawing the Tatar legislature that had opposed Russia’s annexation of the region since 2014. Together with Russian military provocations against NATO forces in and around the Baltic, this move seems to validate the observations of Western analysts who argue that under Vladimir Putin, an increasingly aggressive Russia is determined to dominate its neighbors and menace Europe.

Leaders in Moscow, however, tell a different story. For them, Russia is the aggrieved party. They claim the United States has failed to uphold a promise that NATO would not expand into Eastern Europe, a deal made during the 1990 negotiations between the West and the Soviet Union over German unification. In this view, Russia is being forced to forestall NATO’s eastward march as a matter of self-defense.

The West has vigorously protested that no such deal was ever struck. However, hundreds of memos, meeting minutes and transcripts from U.S. archives indicate otherwise. Although what the documents reveal isn’t enough to make Putin a saint, it suggests that the diagnosis of Russian predation isn’t entirely fair. Europe’s stability may depend just as much on the West’s willingness to reassure Russia about NATO’s limits as on deterring Moscow’s adventurism.

This was written two years after the Russian annexation of Crimea.

The academic article on which it’s based is here.

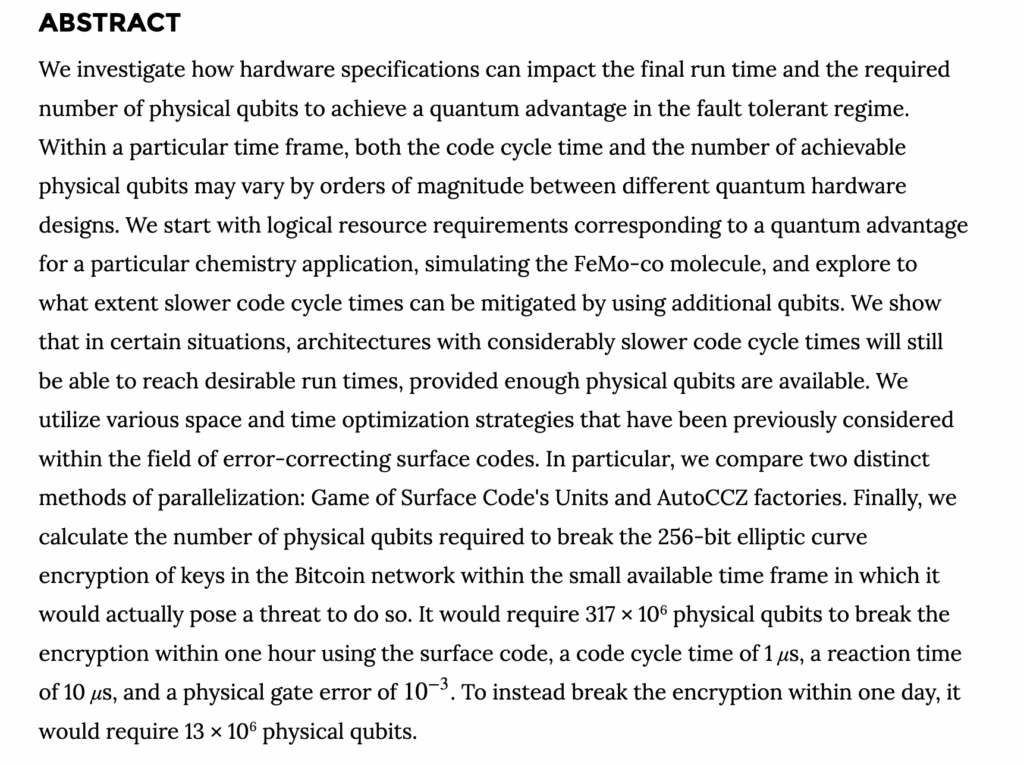

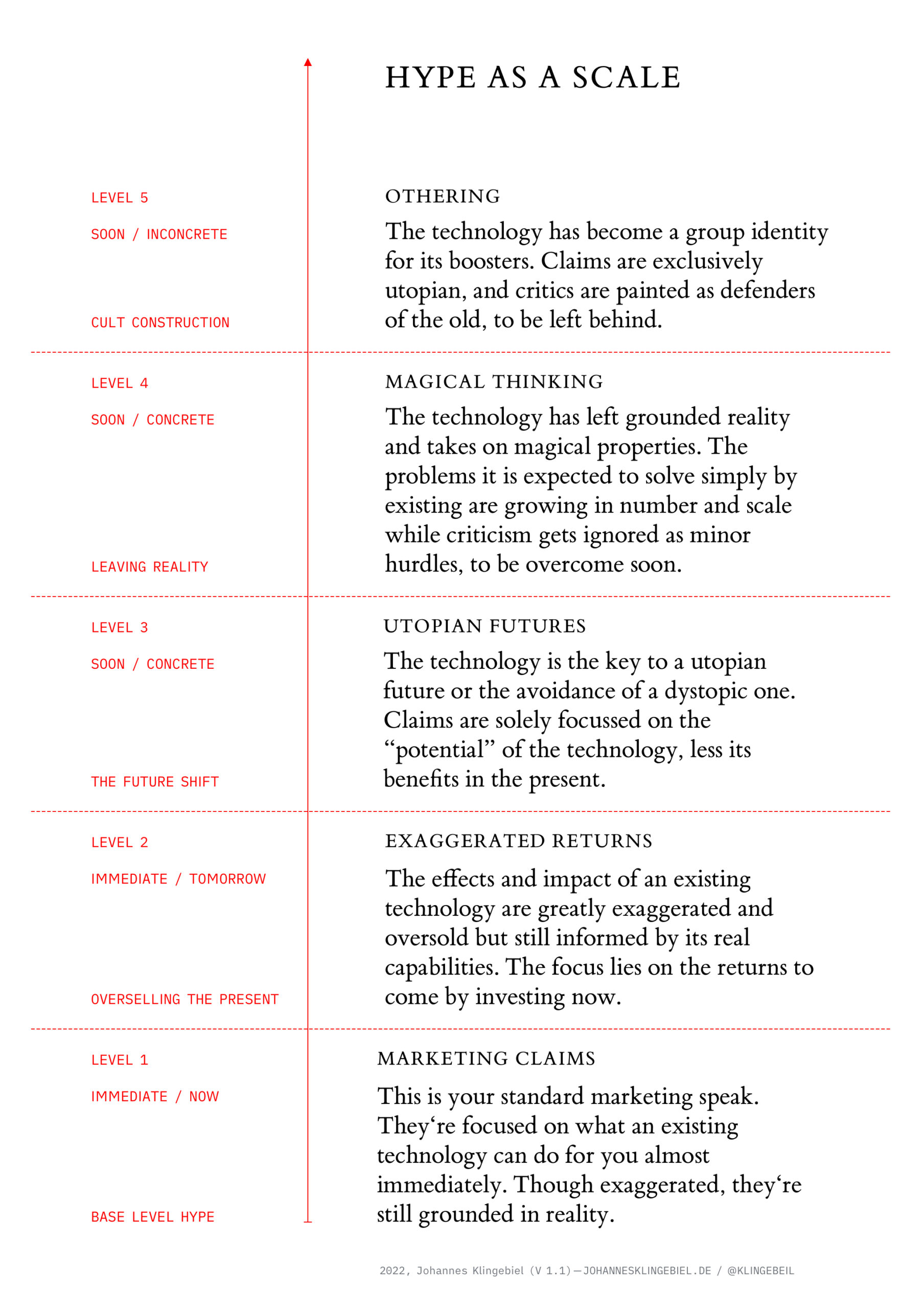

What real transparency looks like

Molly White is one of the sharpest and technically informed critics of the current crypto bubble. She also has an exemplary ‘full disclosure’ page on her blog. It goes like this:

I strongly believe in clear disclosures by journalists and others writing about cryptocurrencies and related topics.

I own no cryptocurrencies or NFTs. I have no particular financial interest in whether web3 takes off or not, though I have plenty of non-financial interests; after all, I do have to live on this planet, and I spend enough time engaging with the tech industry and online to care about the futures of both.

I am not paid to write about cryptocurrencies or related topics, nor am I paid to create my Web3 Is Going Great project. I don’t post sponsored content on that website, its associated Twitter account, this website, my blog, my personal Twitter account, or anywhere else. A few generous people have sent money to me via Twitter tips with comments about Web3 Is Going Great; I have earmarked that money for cloud hosting costs, which I otherwise pay out of pocket. I don’t run ads or otherwise make money in any way off the project or my blog.

I hold no long or short positions pertaining to cryptocurrencies or crypto-related companies. I do have some investments in the stock market and other traditional forms of finance, which I pay someone much smarter about and more interested in finance than I am to handle.

For those who think it is crucial to have interacted with crypto to write about it: 1) you are wrong, but 2) you will be pleased to know that I went through the process of signing up for a Coinbase account and buying one popular cryptocurrency and one shitcoin towards the end of 2021, around when I was starting my deeper research into this space. I sold all of them a week and a half later and closed the account. I made a whopping profit of $16.90 off the whole endeavor (pre-tax).

I wish more people writing about this stuff were as forthcoming.

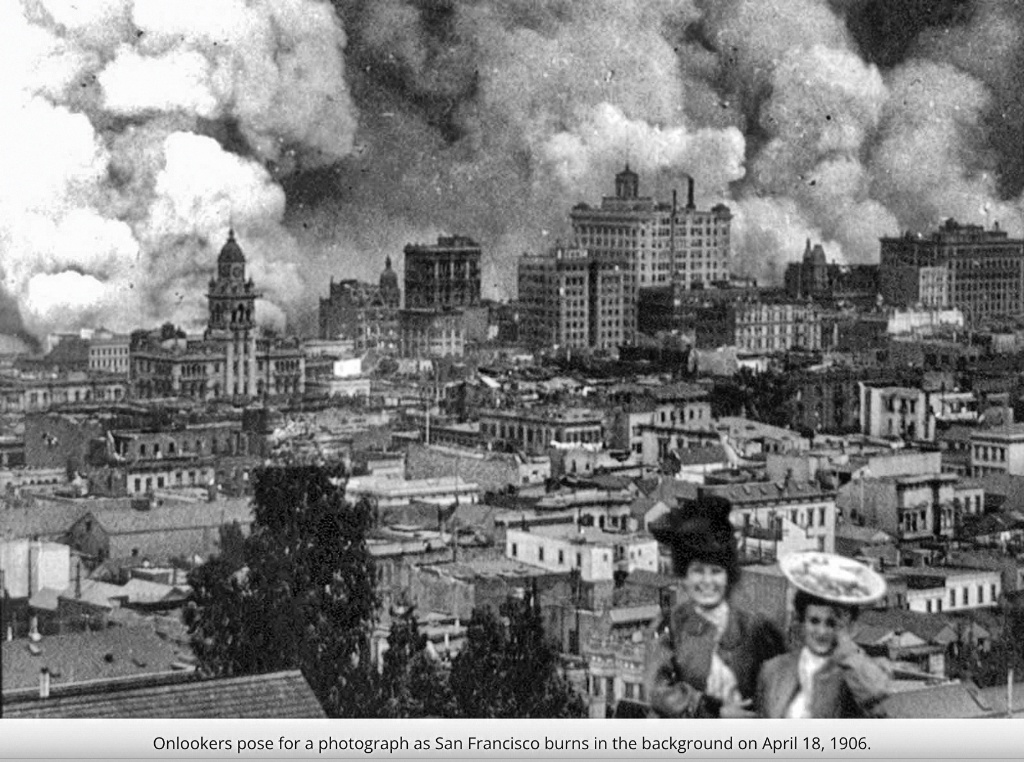

War in Europe is unthinkable — until it isn’t

Funny how complacent we’ve become. This from the New York Times…

But just how far Europe is prepared to go in shifting from a world where peace and security were taken for granted remains to be seen. For decades Europeans have paid relatively little in money, lives or resources for their defense — and paid even less attention, sheltering under an American nuclear umbrella left over from the Cold War.

That debate had begun to shift in recent years, even before Russia’s menacing of Ukraine, with talk of a more robust and independent European strategic and defense posture. But the crisis has done as much to expose European weakness on security issues as it has to fortify its sense of unity.

Ms. Franke, 34, a senior fellow with the European Council on Foreign Relations, is not convinced that anything short of a major Russian invasion of Ukraine will very much alter public opinion.

“We’re having in Europe and Germany a status quo problem,” she said in an interview. “We’re very comfortable with this version of European security, and most people don’t realize that to defend this status quo we need to act.”

The elite feels the cold wind from Russia, she said, but “on the level of public opinion, people want to be left alone and for nothing to touch them.”

My commonplace booklet

How insulated glass changed architecture

Interesting 8-minute video Insulated glass shaped the look of the 20th century. Big but poorly insulated glass windows went out of fashion as electricity enabled artificial lighting. Builders needed a new way to install windows that let in natural light, but also controlled heat. Insulated glass was that solution. Link

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!