Splendid isolation

Quote of the Day

”I’m not crazy about reality, but it’s still the only place to get a decent meal.”

- Groucho Marx

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Jimmy Yancey | The Rocks

Long Read of the Day

Bertrand Russell: In praise of idleness

From way back (1932) but still great. Contains his wonderful definition of ‘work’, which I still cite when puzzled people ask me what I ‘do’.

Why Jeff Bezos’ Anti-Biden Tweets Are So Dumb

Another sharp column by Jack Shafer.

Why do the billionaires tweet? The subject here, of course, is the motivation of the Ironmen of Twitter ego-tripping, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos — not Bill Gates, whose tweets taste like weak dishwater, neither sudsy nor drinkable.

Musk tweets because his obsessive-compulsive disorder commands him to chime in on everything from his investments to his crackpot Covid-19 views to pronouns (they “suck”) to rude comments about Gates to name-calling (Elizabeth Warren, in his eyes, is a “Karen”) to raising the ire of the Securities and Exchange Commission. “Some people use their hair to express themselves, I use Twitter,” Musk tweeted in 2019.

Amazon mogul Bezos, who tragically can’t use his hair to express himself, has chosen to straddle the zone between junk mail from Gates and Musk’s shitposting. Last week, when President Joe Biden published a silly tweet saying that taxing billionaires will cure inflation, Bezos responded Musk-style that the Disinformation Governance Board should investigate that pitch.

I particularly like this bit:

Bezos should consider how counterproductive his Twitter spats with the president and his fellow mogul are. Whether he likes it or not, he’s now the face of the Washington Post. Twitter fulminations may give Bezos a Blue Origin rush of ego-gratification, but why should the man who owns an entire dairy get such a kick out of sipping from a personal-sized milk carton?

Yep.

Musk doesn’t care about spam-bots

He’s trying to find a way of wriggling out of the contract to buy Twitter. Bloomberg’s Matt Levine is having none of it. Quite right too.

The battle over bots has become a sticking point for Musk, who told a tech conference in Miami on Monday that fake users make up at least 20% of all Twitter accounts, possibly as high as 90%. Twitter regularly states in its quarterly results that the average of false or spam accounts “represented fewer than 5% of our monthly daily active users during the quarter,” adding that it applied “significant judgment” to its estimate, and the true number could be higher.

I think it is important to be clear here that Musk is lying. The spam bots are not why he is backing away from the deal, as you can tell from the fact that the spam bots are why he did the deal. He has produced no evidence at all that Twitter’s estimates are wrong, and certainly not that they are materially wrong or made in bad faith. (Musk can only get out of the deal if Twitter’s filings are wrong in a way that would cause a “material adverse effect” on Twitter, which is vanishingly unlikely.)

And…

More important, nothing has changed about the bot problem since Musk signed the merger agreement. Twitter has published the same qualified estimate — that fewer than 5% of monetizable accounts are fake — for the last eight years. Musk knew those estimates, and declined to do any nonpublic due diligence before signing the merger agreement. He knew about the spam bot problem before signing the merger agreement, as we know because he talked about it constantly, including while announcing the merger agreement. If he didn’t want to buy Twitter because there are spam bots, he should not have signed a contract to buy Twitter. No new information has come to light about spam bots in the last three weeks.

So what’s going on? Well, first of all Musk’s $54.20/share price is increasingly looking ludicrous, given that tech stocks are way down since the so-call ‘deal’ was struck.Secondly, Tesla stock — which he is depending on to finance part of the purchase price, has also gone down almost 30%, making him poorer and making the $54.20 price look even dafter. So he is trying to renegotiate the deal for obvious reasons. But, as Levine points out, “that is very clearly not allowed by the merger agreement that he signed: Public-company merger agreements allocate broad market risk to the buyer, and he can’t get out just because stocks went down”.

We haven’t reached even the end of the beginning of this farce. And Matt Levine is a great observer of it.

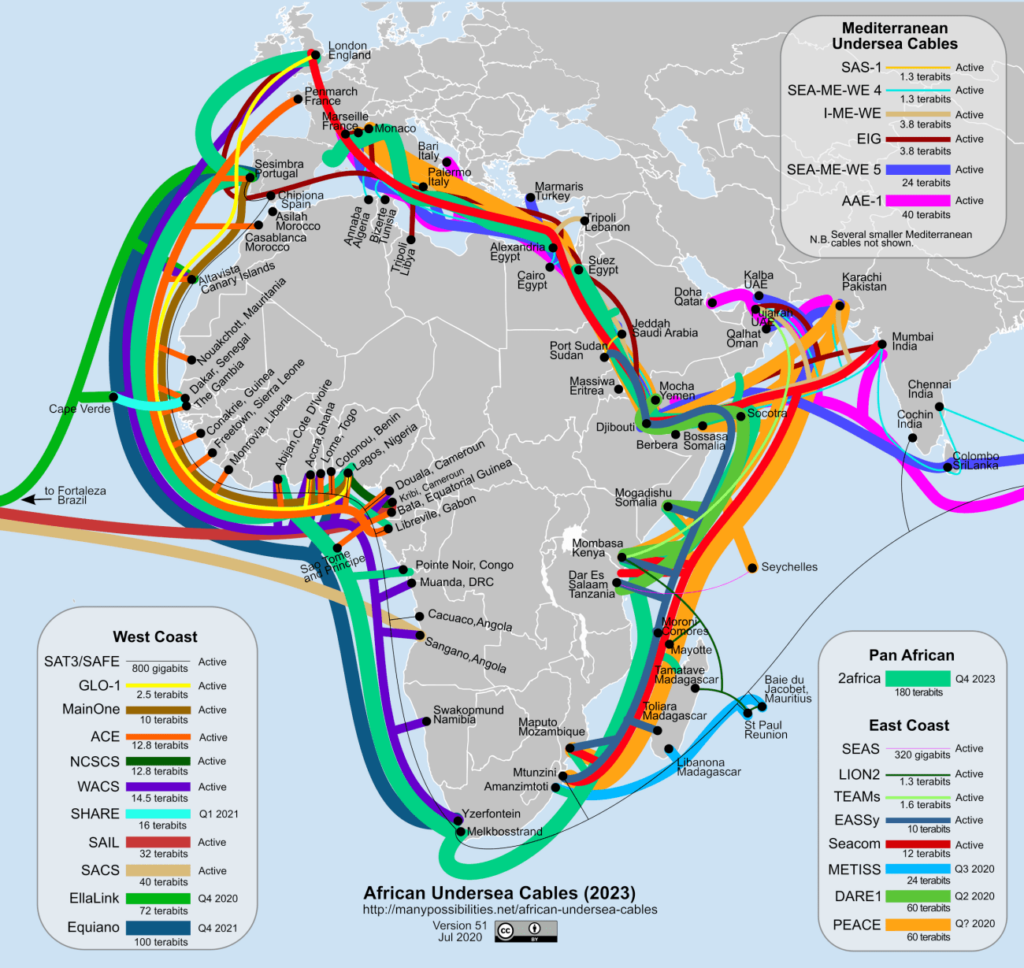

Chart of the Day

My commonplace booklet

Meet the amateur archivists streaming old VHS tapes online Link.

Well, someone has to do it.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!