Street scene, outside Great St Mary’s, Cambridge. Flickr version here.

Moderating RIPA (slightly)

When RIPA was being pushed through Parliament in 1999, some of us were very concerned at its apparent extensibility — especially (i) the scope it offered for its powers to be extended virtually without limit to any public authority in the UK, and (ii) its use for purposes other than detecting organised crime and terrorism. And lo! it came about — the Act has been used by Local Authorities to legitimise snooping in all kinds of areas, none of them connected with terrorism or organised crime.

The abuses have become so outrageous that now there’s to be a public consultation on the matter. here’s the text of the official announcement:

Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000: Consolidating orders and codes of practice

Passed in 2000, the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (called RIPA), created a regulatory framework to govern the way public authorities handle and conduct covert investigations.

This consultation takes a look at all the public agencies, offices and councils that can use investigation techniques covered by RIPA, and asks the public to consider whether or not it’s appropriate for those people to be allowed to use those techniques.

In light of recent concerns, the government is particularly interested in how local authorities use RIPA to conduct investigations into local issues. Among other things, in order to ensure that RIPA powers are only used when they absolutely need to be, the government proposes to raise the rank of those in local authorities who are allowed to authorise use of RIPA techniques.

To respond to the consultation, reply by email to ripaconsultation@homeoffice.gsi.gov.uk

You can also reply by post to:

Tony Cooper

Home Office

Peel Building 5th Floor

2 Marsham Street

London SW1P 4DF

A convention of cant?

Conor Gearty was not impressed by the Convention on Modern Liberty.

I first wrote that Britain was in danger of becoming a police state in the New Statesman, in June 1986. The occasion was the Public Order Bill that was then before parliament. Our civil liberties were being “horribly squeezed”, as I saw it, by an increase in police power that was producing a “distressing drift into discretionary law”. I ended by declaring that a “police state, even a benevolent one, is not a free society for long”. I wish now I had not used that phrase: it was too shrill for the circumstances it sought to describe, drawing too quick a conclusion from too flimsy a factual base. Yet if we are to believe many of the enthusiastic champions of freedom at the recent Convention on Modern Liberty we are still – 23 years later – on our way to becoming a police state or a “surveillance society” or whatever the latest colourful label is to describe the decline of freedom in Britain. The point is as overstated today as it was in 1986.

First it reveals a serious lack of historical perspective. When was this golden age from which we measure the decline?

Worth reading in full. Thanks to Charlie Beckett for spotting it.

Footnote: Cant is a great word, but I’m not sure Conor’s use of it is entirely accurate. Its origins are obscure, though some people claim it’s derived from the Irish ‘caint’, which means talk. (A nice touch since Prof Gearty and I are both Irish.) But Wikipedia claims that “the original meaning of ‘cant’ was a secret language supposedly used by rogues and vagabonds in Elizabethan England. This Thieves’ Cant was a feature of popular pamphlets and plays particularly between 1590 and 1615, but continued to feature in literature through the 18th century.” The Shorter Oxford doesn’t mention this at all, but has lots of different definitions (e.g. creek, border, edge, portion, share, division, musical sound, singing, sale by auction, apportion, give an oblique or slanting edge to), only two of which seem appropriate to its use as a term of abuse: ‘a whining manner of speaking’; and ‘jargonistic, ephemerally fashionable, uttered mechanically’.

Hashmobs

Nicholas Carr was, predictably, not impressed by the #amazonfail business:

Flashmobs were okay, but they had a couple of big downsides. First, they required you to go outside. Second, you had to, well, be in a flashmob.

Hashmobs solve both problems by transferring the flashmob concept into a purely realtime environment. A hashmob is a virtual mob that exists entirely within the Twitter realtime stream. It derives its name not from any kind of illicit pipeweed but from the “hashtags” that are commonly used to categorize tweets. Hashtags take the form of a hash sign, ie, #, in front of a word or word-portmanteau, eg, #obama or #obamadog. The members of a hashmob gather, virtually, around a particular hashtag by labeling each of their tweets with said hashtag and then following the resulting hashtag tweet stream. Hashmobbers don’t have to subject themselves to the weather, and they don’t actually have to be in proximity to any other physical being. A hashmob is a purely avatarian mob, though it is every bit as prone to the rapid cultivation of mass hysteria as a nonavatarian mob….

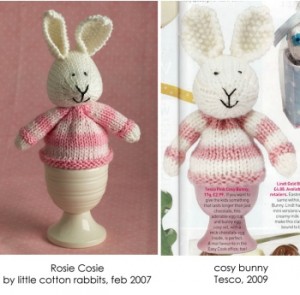

Tesco: every little helps, er, Tesco

Guess how much Tesco paid for the rights to Rosie Cosie?

Then check your estimate here.

(Prediction: the next step will be a letter from Tesco lawyers accusing Julie Williams for using the image of Tesco Cosy Bunny without permission.)

UPDATE: The link to her blog no longer works. Ms Williams has taken her post offline. She explains:

A quiet thank you

I had no idea that things would escalate to such proportions when I wrote about my egg cosy problems earlier today. I need to sleep on the whole matter and consider some of the very valid points that have been raised. This is a matter for me and one that only affects me and my very little business. To see things snowballing from a small and personal matter is a little disconcerting, and the reason I’ve taken my post off-line for now.

Wonder what happened?

Family life

Seen in the window of proud grandparents. Flickr version here.

Amazon, Google and Juvenal: Quis custodiet…

Jeff Bezos’s mantra from the moment he founded Amazon was “get big quick”. We’re beginning to see just how big it’s getting.

Last week an investment analyst estimated that Amazon now ‘facilitates’ (and takes a cut from) a third of all e-commerce transactions in the US.

Then the gay and lesbian community discovered how powerful Amazon’s database can be when what the company later described as an “embarrassing and ham-fisted cataloging error” effectively banned 57,310 listings of so-called ‘adult’ books and DVDs by making them invisible. This saga was well covered on the Web. See, for example, Clay Shirky’s admirable apologia (for being seduced by righteousness), Bill Thompson’s BBC column and Rory Cellan-Jones’s early blog post on the subject.

Looming over all this, of course, is a Really Big Question. Companies like Amazon and Google have acquired enormous power. Both can effectively render significant chunks of our culture invisible at the click of a mouse. But they are public corporations, answerable only to their shareholders — if at all. (Actually, in Google’s case, the two-tier shareholding structure means that the company’s leaders are not accountable even to their shareholders.) So, as the Roman poet Juvenal famously observed: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? (Who will guard the guards themselves?) To date, we’ve avoided the question, arguing that if companies step out of line then in a competitive market they will pay the penalty for messing us around. So, if Google was deliberately skewing search results (so the argument runs) then the market would detect that and people would go to other search engines. I suspect we’ve moved beyond that comforting point. So the question remains: who will keep these online behemoths honest?

A philosopher discovers Twitter

Tom Morris via HuffPost.

There is communal thinking on Twitter on a level and in a form I’ve never seen before. Almost every day, a topic comes up that causes me, as a philosopher, to ponder a bit, and then share the results of that pondering in the 140 character increments that Twitter allows. Today, someone mentioned Susan Boyle, the lady who has made such a stir worldwide with her recent appearance on the television show Britain’s Got Talent. The You Tube video is at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9lp0IWv8QZY.

As I reflected and tweeted briefly on Susan and her lessons for the rest of us, people started retweeting, or passing along those short reflections to others. When I saw what touched people the most, and elicited the best responses, that in turn informed what I continued to think and tweet. While considering all the activity that these simple tweets generated, because of who Susan Boyle is and what she’s shown us, I decided to use an extra blog post today simply to share these tweets, or twitter reflections, to provide an example of the unlikely musing that is now flashing around the internet, and also to highlight Susan’s example for us in this forum as well…

Life After Newspapers — and spelling

Just browsing this WashPost piece by Michael Kinsley when I came on this para.

It is tempting, but too easy, to say the problems of newspapers are their own fault. True enough, the industry missed a whole armada of boats. If newspapers had been smarter, or moved faster, they might have kept the classified ads. They might have invented social networking. But that’s all hindsight. I didn’t think of these things, nor did you. Judging from Tribune Co., for which I once worked, the typical newspaper executive is a bear of little brain. Until recently, little brain was needed. Even now, to say the newspaper industry has no problems that a busload of geniuses couldn’t solve is essentially saying that the industry’s problems are insoluable. Or at least insoluable without help.

Hmmm… Insoluable indeed. Maybe someone should donate a spell-checker to the poor impoverished Washington Post. But that reference to “a bear of little brain” comes from Winnie the Pooh, whose spelling — you will recall — was “good spelling but it wobbles”.

That aside, it’s a nice piece.

Wikipedia opts out of Phorm

Here’s the text of the memo to the Phorm administrators:

The Wikimedia Foundation requests that our web sites including

Wikipedia.org and all related domains be excluded from scanning by the

Phorm / BT Webwise system, as we consider the scanning and profiling of

our visitors’ behavior by a third party to be an infringement on their

privacy.

Good stuff. This suggests a tactic for a flash-mob operation. If millions of domain owners emailed website-exclusion@webwise.com with demands that their domains be excluded it might have an interesting effect.

Interesting to see that Amazon has already opted out.

Interesting also to see that info about opting out is pretty deeply buried on the BT Webwise site. The relevant para says:

How can I remain opted-out of BT Webwise even if I delete cookies regularly?

We provide the facility to block cookies permanently from BT Webwise so if you want to opt out permanently you can do so through a one-time only activity, by setting your browser to block cookies from the domain webwise.net. When you block this domain, the service will not put a cookie on your machine and you will not be asked to opt in or out again.