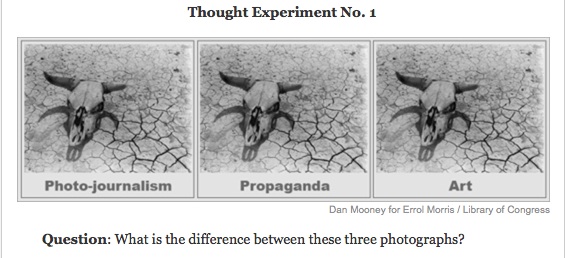

… on unauthorised ingenuity, to wit this:

According to Wired,

the latest update to Snow Leopard, version 10.6.2, drops support for the Intel Atom processor. This means that anyone with a “hackintosh” who tries to update to the latest operating system version will see their computer die, going no further than the gray Apple logo on startup.

The reports are lighting up various hackintosh forums, and OSx86-co-author wizard Stellarolla sums it up thusly:

“Well, looks like I was right, again. The netbook forums are now blowing up with problems of 10.6.2 instant rebooting their Atom-based netbooks. My sources tell me that every time a netbook user installs 10.6.2 an Apple employee gets their wings.”

It shouldn’t be long before some clever hacker figures out a workaround and releases a patched kernel to the world, re-enabling the OS on Atom-based computers. But that’s not the story. The bigger message is that Apple has finally stopped ignoring the incessant buzz of the hobby-hacking, Mac netbook scene and instead pulled out a fly-swatter and dealt it a whack. The war is officially on.

Hee, hee! Thanks to a warning from Quentin, I shan’t be ungrading for the time being. And my lovely little Dell/Apple hybrid will continue to be a delightful workhorse.

The thing that gave me most pleasure when I hacked the Dell in the first place was that I was simultaneously annoying two of the world’s great control freaks! Apple’s latest gambit only increases the pleasure.