Michael’s birthday present. Flickr version here.

The holy well

Flickr version here.

This academic life…

Broad Street, Oxford, on Wednesday. Flickr version here.

Only the paranoid survive

Interesting insight from a recent speech given in Dublin by Google’s European sales chief.

Google believes that in three years or so desktops will give way to mobile as the primary screen from which most people will consume information and entertainment. That’s according to Google Europe boss John Herlihy who said that smart phones enhance Google’s mission to make information universal.

Speaking at the Digital Landscapes conference at UCD, Herlihy said that the cloud-computing opportunity will make sure that every mobile device will be capable of doing rapid-scale applications.

“In three years time, desktops will be irrelevant. In Japan, most research is done today on smart phones, not PCs,” Herlihy told a baffled audience, echoing comments by Google CEO Eric Schmidt at the recent GSM Association Mobile World Congress 2010 that everything the company will do going forward will be via a mobile lens, centring on the cloud, computing and connectivity.

“Mobile makes the world’s information universally accessible. Because there’s more information and because it will be hard to sift through it all, that’s why search will become more and more important. This will create new opportunities for new entrepreneurs to create new business models – ubiquity first, revenue later.”

In fact, the disruptive effect that Sergey Brin and Larry Page had on the internet when they were maxing out credit cards in 1998 to buy servers to build their search engine haunts Google to this day, Herlihy said.

“The fear is the next Sergey and Larry will come up with a disruptive technology or service that will eliminate the need for Google. That spurs us on to deliver the best quality return on investment to advertisers in an open and transparent partnership that works for them.

“There is a tremendous opportunity for entrepreneurs to end the need for Google. It’s our challenge not to let that happen by continuing to drive innovation and value.”

Apple goes after Android

Rather than take on Google directly, Apple has sued HTC, the manufacturer which makes most of the handsets currently running the Android operating system. But to the detached observer, it’s clear what the real target is. Here’s GMSV’s take on it:

Although not named in Apple’s suits accusing HTC of multiple violations of iPhone-related patents, Google made a point Tuesday of publicly declaring its support for the company that makes many of the most popular Android-based smartphones, including the Google-branded Nexus One. “We are not a party to this lawsuit,” a spokesman told TechCrunch. “However, we stand behind our Android operating system and the partners who have helped us to develop it.” Unless Google can come up with a reason to turn loose its own legal hounds in a counterattack against Apple, however, that support, whatever form it takes, will be coming from the sidelines. In an effort clearly aimed at halting the Android advance, Apple avoided tangling with the search sovereign mano a mano and instead hit the HTC flank, opening the possibility of winning a U.S. International Trade Commission injunction sealing the border against any HTC phones found to be infringing.

Judging by HTC’s latest statement regarding the action, it may already have gotten some advice from Google on framing its position in the court of public opinion. In advising stockholders that it doesn’t expect the Apple suits to have any short-term material impact or affect Q1 guidance, HTC flew the freedom-of-choice banner, saying, “HTC believes that consumer choice is a key component to success in the smartphone industry and this is best achieved through multiple suppliers providing a variety of mobile experiences. HTC has focused on offering its customers a uniquely-HTC experience through HTC Sense and its broad portfolio of smartphones.”

Where things go from here is anyone’s guess — ITC action, countersuits and amended complaints, out of court settlement, royalties, IP sharing, full review of the patents themselves. But as a first-strike FUD missile, Apple’s litigation seems to be doing its job right now.

What it suggests to me is that Android is beginning to bite, in the sense that Apple thinks it may turn out to pose a strategic threat to the iPhone/iPad market.

Toyota recall: latest

A musician friend who knows that we have a Prius sent us this:

In response to Toyota’s massive car recall: Yamaha has recalled 20,000 pianos due to a problem with the pedal sticking, causing pianists to play faster than they normally would, resulting in a dangerous number of accidentals. The sticky pedal also makes it harder for pianists to stop at the end of the piece, making it extremely risky for the audience.

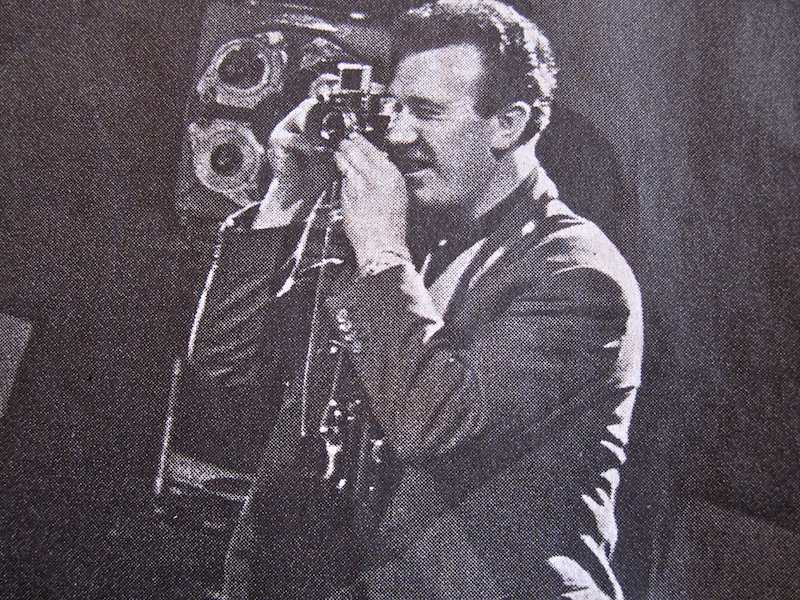

Bill Francis and his kit

The Guardian had a nice obit of photographer Bill Francis today which included the observation that he was “passionate about his cameras and equipment, Bill always had the best, favouring a Hasselblad and his family of Leicas.”

But the photograph used to illustrate the piece shows him with a Rolleiflex and a 35mm camera which may or may not be a Leica and indeed might even be a Zeiss Ikonta — viz:

Not a Hasselblad in sight.

LATER: On reflection, I think he is using a Leica. An M3, maybe.

A tale of two headlines

The paradoxical market for news

There’s a strange paradox in the current gloom afflicting news organisations. On the one hand, the journalistic doomsters believe there is no longer a market for what they produce. On the other hand there’s the Pew Internet & American Life Project’s report which seems to suggest that people can’t get enough of it (news, that is).

In the digital era, news has become omnipresent. Americans access it in multiple formats on multiple platforms on myriad devices. The days of loyalty to a particular news organization on a particular piece of technology in a particular form are gone. The overwhelming majority of Americans (92%) use multiple platforms to get news on a typical day, including national TV, local TV, the internet, local newspapers, radio, and national newspapers. Some 46% of Americans say they get news from four to six media platforms on a typical day. Just 7% get their news from a single media platform on a typical day.

The internet is at the center of the story of how people’s relationship to news is changing. Six in ten Americans (59%) get news from a combination of online and offline sources on a typical day, and the internet is now the third most popular news platform, behind local television news and national television news.

The process Americans use to get news is based on foraging and opportunism. They seem to access news when the spirit moves them or they have a chance to check up on headlines. At the same time, gathering the news is not entirely an open-ended exploration for consumers, even online where there are limitless possibilities for exploring news. While online, most people say they use between two and five online news sources and 65% say they do not have a single favorite website for news. Some 21% say they routinely rely on just one site for their news and information.

I suppose that whaat it comes down to is whether there’s a difference between a demand for something and a market for it. Conventional economics would say that where there’s a demand, there’s always a market.