The New York Times has a thoughtful set of contributions from various experts on the significance of the WikiLeaks disclosures.

Evgeny Morozov, a Stanford scholar who has a book about the “dark side of Internet freedom” coming out in January, ponders the likelihood that WikiLeaks can be duplicated, and finds it unlikely.

A thousand other Web sites dedicated to leaking are unlikely to have the same effect as WikiLeaks: it would take a lot of time and effort to cultivate similar relationships with the media. Most other documents leaked to WikiLeaks do not carry the same explosive potential as candid cables written by American diplomats.

One possible future for WikiLeaks is to morph into a gigantic media intermediary — perhaps, even something of a clearing house for investigative reporting — where even low-level leaks would be matched with the appropriate journalists to pursue and report on them and, perhaps, even with appropriate N.G.O.’s to advocate on their causes. Under this model, WikiLeaks staffers would act as idea salesmen relying on one very impressive digital Rolodex.

Ron Deibert from the University of Toronto thinks that the “venomous furor” surrounding WikiLeaks, including charges of “terrorism” and calls for the assassination of Julian Assange, has to rank as “one of the biggest temper tantrums in recent years”.

Many lament the loss of individual privacy as we leave digital traces that are then harvested and collated by large organizations with ever-increasing precision. But if individuals are subject to this new ecosystem, what would make anyone think governments or organizations are immune? Blaming WikiLeaks for this state of affairs is like blaming a tremor for tectonic plate shifts.

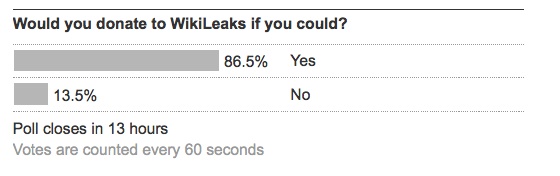

Certainly a portion of that anger could be mitigated by the conduct of WikiLeaks itself. The cult of personality around Assange, his photoshopped image now pasted across the WikiLeaks Web site, only plays into this animosity. So do vigilante cyberattacks carried out by supporters of WikiLeaks that contribute to a climate of lawlessness and vengeance seeking. If everyone can blast Web sites and services with which they disagree into oblivion — be it WikiLeaks or MasterCard — a total information war will ensue to the detriment of the public sphere.

An organization like WikiLeaks should professionalize and depersonalize itself as much as possible. It should hold itself to the highest possible ethical standards. It should act with the utmost discretion in releasing into the public domain otherwise classified information that comes its way only on the basis of an obvious transgression of law or morality. This has not happened.

Ross Anderson, who is Professor of Security Engineering at Cambridge and the author of the standard textbook on building dependable distributed information systems, thinks that the WikiLeaks saga shows how governments never take an architectural view of security.

Your medical records should be kept in the hospital where you get treated; your bank statements should only be available in the branch you use; and while an intelligence analyst dealing with Iraq might have access to cables on Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia, he should have no routine access to information on Korea or Zimbabwe or Brazil. But this is in conflict with managers’ drive for ever broader control and for economies of scale.

The U.S. government has been unable to manage this trade-off, leading to regular upsets and reversals of policy. Twenty years ago, Aldrich Ames betrayed all the C.I.A.’s Russian agents; intelligence data were then carefully compartmentalized for a while. Then after 9/11, when it turned out that several of the hijackers were already known to parts of the intelligence community, data sharing was commanded. Security engineers old enough to remember Ames expected trouble, and we got it.

What’s next? Will risk aversion drive another wild swing of the pendulum, or might we get some clearer thinking about the nature and limits of power?

James Bamford, a writer and documentary producer specializing in intelligence and national security issues, thinks that the WikiLeaks disclosures are useful in forcing governments to confess.

A generation ago, government employees with Communist sympathies worried security officials. Today, after years of torture reports, black sites, Abu Ghraib, and a war founded on deception, it is the possibility that more employees might act out from a sense of moral outrage that concerns officials.

There may be more employees out there willing to leak, they fear, and how do you weed them out? Spies at least had the courtesy to keep the secrets to themselves, rather than distribute them to the world’s media giants. In a sense, WikiLeaks is forcing the U.S. government into the confessional, with the door wide open. And confession, though difficult and embarrassing, can sometimes cleanse the soul.

Fred Alford is Professor of Government at the University of Maryland and thinks that neither the Web operation WikiLeaks, nor its editor-in-chief, Julian Assange, is a whistle-blower.

Whistle-blowers are people who observe what they believe to be unethical or illegal conduct in the places where they work and report it to the media. In so doing, they put their jobs at risk.

The whistle-blower in this case is Bradley Manning, an United States Army intelligence analyst who downloaded a huge amount of government classified information, which was made public by WikiLeaks. Whether or not Manning’s act serves the greater public interest is a contentious issue, but he has been arrested and charged with unlawful disclosure of classified data.

Some have compared the role of WikiLeaks to that of The New York Times in the publication of the Pentagon Papers several decades ago. WikiLeaks is the publishing platform that leverages the vast and instantaneous distribution capacity of the Internet.

The WikiLeaks data dump challenges a long held belief by many of us who study whistle-blowing — that it is important that the whistle-blower have a name and face so that the disclosures are not considered just anonymous griping, or possibly unethical activity. The public needs to see the human face of someone who stands up and does the right thing when none of his or her colleagues dare.

But he also thinks that “for better and worse, this changes whistle-blowing as we’ve known it.”