It’s funny how people never learn. This useful report from Good Morning Silicon Valley brings back memories of the first Internet boom, and of the unscrupulous role that, ahem, major investment banks played in fuelling the lunacy. GMSV notes a WSJ article stating that Facebook’s 2009 profit was $200 million on revenue of $700 million, and goes on:

The New York Times’ DealBook reports today that Goldman Sachs Capital Partners, a $20.3 billion investment fund, was given first dibs at the Facebook investment but declined because of concern that the Palo Alto company’s $50 billion valuation is too high. The report also cited unnamed sources who say Facebook’s 2010 net income was $400 million on revenue of $2 billion. A Bloomberg report compares Facebook to Google: A $50 billion valuation is about 25 times the reported 2010 revenue, while Google’s price-to-sales ratio is estimated at 9. Another Facebook-Google comparison of note comes from Connie Loizos at peHUB: “When Google went public in 2004, it steered clear of sweetheart deal-making. … Deals like that of Facebook-Goldman reek of an old boys club way of doing business.”

Yep. Even if I had any money (which I don’t) and was minded to invest in tech stocks (which would be unethical, given my newspaper column) I wouldn’t ever touch a deal in which Goldman was involved. This, after all, is the bank that was recently fined for screwing its own clients. And now some of those saps are stampeding to get a ludicrously overpriced slice of the Facebook action. In ordinary life, they say that one sucker is born every minute. In the stock market, their birth rate seems to be considerably higher.

Later: It seems that the minimum investment Goldman requires for anyone who want to be involved in its Facebook fund is $2m. For disconsolate souls who don’t have that much money to lose, Silicon Valley Insider has this consoling news:

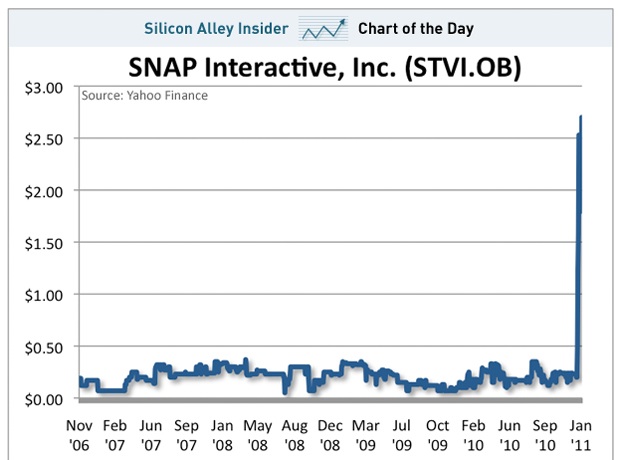

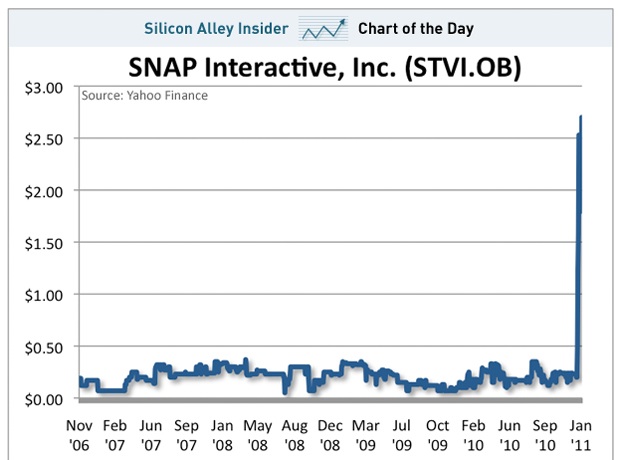

There’s a fun penny stock called Snap Interactive, whose fortune is tied to Facebook.

The company has the most popular dating app on Facebook and charges a small fee for some users. It’s managed to generate $2.7 million in revenue last quarter up from $1.7 million the quarter before.

That growth has gotten some investors attention, and now the stock price is soaring — its up over 1,000% in the last 30 days. So, if you want to roll the dice, and you want to play a Facebook company on the public markets, here’s your chance.

Er, their chart suggests that you may have missed even that boat.

This looks like a bubble to me, folks, with Goldman Sachs manning the airpump. The strategy seems clear: to stampede Facebook into a flotation by triggering the SEC rules that a company with more than 499 shareholders has to float.

In the interests of balance… I should point out that not everyone agrees with me that Facebook is over-valued at $50 billion.