… I dislike pubs (and beer) — and like coffee. Politics can be so difficult, sometimes. Sigh.

Why the BBC has to call time on the Andrew Marr show

I was about to write a post about Andrew Marr’s expressions of regret about resorting to a dubious legal method of gagging the media, but found that Charlie Beckett has expressed it better.

Like any citizen Marr had a perfect right to defend his privacy. But as a journalist he must have realised his legal actions would reduce his credibility as someone who can interrogate the powerful and famous about their personalities as well as their policies and actions.

It’s not his fault that the judges (or rather one judge in particular) has decided to extend the power of the the super-injuction to a point where corporations as well as celebs can avoid exposure. But it is his fault that he took advantage of it. (Of course, the Internet has made even the most super of injunctions a fallible tool for suppression but they still keep the facts out of the general public’s gaze – perhaps that’s why Marr was so rude about bloggers.)

Marr now admits that his actions were hypocritical, but I think it’s worse than that and that’s why he shouldn’t really be doing political interviews anymore. He is a very clever man who has written the best ‘straight’ history of British journalism we have. I hope he continues to broadcast as a presenter of programmes like Start The Week and those popular histories of Britain. But he has now lost any pretence to membership of the Pugilist Tribe.

We need people like Ian Hislop and Private Eye who are prepared to be wrong sometimes in their efforts to get to the truth. Yes, the Pugilists may act out of shallow and malicious motives. They may over-personalise attacks and get their facts wrong or out of perspective. But they are more likely to ruffle the feathers of the mighty. And critically, the best of them don’t see themselves as part of authority.

Yep. Apart from anything else, Marr has been critically weakened by this. He’s a talented and thoughtful man but there’s no way he can credibly take on slippery and evasive public figures from now on. The BBC has to drop the AM show on Sunday mornings. Or find someone with untarnished credibility to do it.

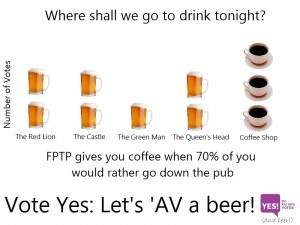

AV explained!

I’m going to vote for AV not just because I think it’ll be marginally better than the current system, but also because if it wins it will tear the Tories apart, and I’m missing the spectacle of internecine warfare on the Right.

Don’t give your data to cloud providers. Just lend it to them.

Interesting NYT column by Richard Thaler.

Here is a guiding principle: If a business collects data on consumers electronically, it should provide them with a version of that data that is easy to download and export to another Web site. Think of it this way: you have lent the company your data, and you’d like a copy for your own use.

This month in Britain, the government announced an initiative along these lines called “mydata.” (I was an adviser on this project.) Although British law already requires companies to provide consumers with usage information, this program is aimed at providing the data in a computer-friendly way. The government is working with several leading banks, credit card issuers, mobile calling providers and retailers to get things started.

To see how such a policy might improve the way markets work, consider how you might shop for a new cellphone service plan. Two studies have found that consumers could save more than $300 a year by switching to the right plan. But to pick the best plan, you need to be able to estimate how much you use services like texting, social media, music streaming and sending photos.

You may not know how to answer or be able to express it in megabytes, but your service provider can. Although some of this information is available online, it’s generally not readily exportable — you can’t easily cut and paste it into a third-party Web site that compares prices — and it is not put together in a way that makes it easy to calculate which plan is best for you.

Under my proposed rule, your cellphone provider would give you access to a file that includes all the information it has collected on you since you owned the phone, as well as the current fees for each kind of service you use. The data would be in a format that is usable by app designers, so new services could be created to provide practical advice to consumers. (Think Expedia for calling plans.) And this virtuous cycle would create jobs for the people who dream up and run these new Web sites.

Life in the technology jungle: the salutary tale of the Flip

This morning’s Observer column.

The Flip was a delicious example of clean, functional design and it sold like hot cakes. From the first day it appeared on Amazon it was the site's bestselling camcorder, and eventually captured 35% of the camcorder market. I bought one as soon as it appeared in the UK, and soon found that my friends and colleagues were eyeing it enviously. One – a keen tennis player – bought one along with an ingenious bendy tripod called a Gorillapod and mounted it on the fence at the court where he was having lessons with his coach. (The coach was not impressed.) Another friend, this time a golfer, bought one and used it to analyse his swing when practising at the driving range. Thousands of YouTube videos were produced using Flips. It was what technology pundits call a “game changer”.

In March 2009 the giant networking company Cisco astonished the world by buying Pure Digital Technologies, the developer of the Flip, for $590m. This seemed weird because Cisco doesn’t do retail: it’s the company that provides the digital plumbing for the internet. It deals only with businesses. It was as if BP had suddenly announced that it was going into the perfume business. But, hey, we thought: maybe Cisco is getting cool in its old age.

How wrong can you be? Just over a week ago, Cisco announced that it was shutting down its Flip video camera division and making 550 people redundant. Just like that…

Privacy in the networked universe

From a comment piece by me in today’s Observer.

Recent events in the high court suggest that we now have two parallel media universes.

In one – Universe A – we find tightly knit groups of newspaper editors and expensive lawyers trying to persuade a judge that details of the sexual relations between sundry celebrities and a cast of characters once memorably characterised by a Glasgow lawyer as “hoors, pimps and comic singers” should (or should not) be published in the public prints.

If the judge sides with the celebs, then he or she can grant an injunction forbidding publication. But because news of an injunction invariably piques public interest (no smoke without fire and all that), an extra legal facility has become popular — the super-injunction, which prevents publication of news that an injunction has been granted, thereby ensuring not only that Joe Public knows nothing of the aforementioned cavortings, but also that he doesn’t know that he doesn’t know.

In the old days, this system worked a treat for the simple reason that Universe A was hermetically sealed. If a judge granted the requisite injunctions, then nobody outside the magic circle knew anything.

But those days are gone. Universe A is no longer hermetically sealed.

It now leaks into Universe B, which is the networked ecosystem powered by the internet. And once news of an injunction gets on to the net, then effectively the whole expensive charade of Universe A counts for nought. A few minutes’ googling or twittering is usually enough to find out what’s going on.

This raises interesting moral dilemmas for Joe Public…

Bahrain Heads for Disaster

From Elliott Abrams.

Bahrain has a Shia majority (once estimated at 70 percent, but probably lower than that now due to a campaign of naturalization of foreign-born Sunnis, especially those who serve in the army and police). The current actions against the Shia community will embitter all its members and decapitate its moderate political, economic, religious, and moral leadership. Future compromises will be far more difficult, and are perhaps already impossible.

Why has the King taken this disastrous path? Clearly he has been urged and pressured to do so by his Sunni neighbors in the UAE and especially Saudi Arabia. The contempt for Shia and Shiism in Saudi Arabia is undoubtedly a key factor here, and the Saudis were concerned that an uprising by Bahraini Shia could spread across to the Shia in their own oil-rich Eastern Province. But the actions being taken in Bahrain now make it far more likely that this will be the outcome: Saudi Shia who see the Saudi government repressing Shia in Bahrain will become more, not less, embittered toward their own government. The Saudis also worried about opportunities for Iran to meddle in Bahrain and ultimately in Saudi Arabia itself. But here again, the policy being followed will only create new chances for Iran by assuring enmity and political volatility in Bahrain.

So the path being followed is disastrous. Perhaps it is not too late for outside figures to try to open a dialogue between the Government of Bahrain and the Shia community, but for that to work the King and the royal family must stop the persecution of the Shia leadership. As of now, they seem intent on crushing the Shia and eliminating all hope of a constitutional monarchy where the majority of Bahrain’s people share with the King a role in building the country’s future. If the King does not change course, he is guaranteeing a future of instability for Bahrain and may be dooming any chance that his son the Crown Prince will ever sit on the throne.

Yep. Bet the Iranians can’t believe their luck. They have such fools for enemies.

How Twitter could put an end to paywalls

Intriguing post by Dave Winer.

Now here’s a chilling thought.

If Twitter wanted to, tomorrow, they could block all links that went into a paywall. That would either be the end of paywalls, or the end of using Twitter as a way to distribute links to articles behind a paywall, which is basically the same thing, imho.

Twitter already has rules about what you can point to from a tweet, and they’re good ones, they keep phishing attacks out of the Twitter community, and they keep out spammers. But that does not have to be the end of it. And if you think Twitter depends on you, I bet Adobe felt that Apple depended on them too, at one point.

And now: the Android spyPhone

From yesterday’s Guardian:

Smartphones running Google’s Android software collect data about the user’s movements in almost exactly the same way as the iPhone, according to an examination of files they contain. The discovery, made by a Swedish researcher, comes as the Democratic senator Al Franken has written to Apple’s chief executive Steve Jobs demanding to know why iPhones keep a secret file recording the location of their users as they move around, as the Guardian revealed this week. Magnus Eriksson, a Swedish programmer, has shown that Android phones – now the bestselling smartphones – do the same, though for a shorter period. According to files discovered by Eriksson, Android devices keep a record of the locations and unique IDs of the last 50 mobile masts that it has communicated with, and the last 200 Wi-Fi networks that it has “seen”. These are overwritten, oldest first, when the relevant list is full. It is not yet known whether the lists are sent to Google. That differs from Apple, where the data is stored for up to a year.

The Apple spyPhone (contd.)

It’s fascinating to see what happened overnight on this story. Firstly, lots of people began posting maps of where their iPhones had been, which is a clear demonstration of the First Law of Technology — which says that if something can be done then it will be done, irrespective of whether it makes sense or not. Personally I’ve always been baffled by how untroubled geeks are about revealing location data. I remember one dinner party of ours which was completely ruined when one guest, a friend who had been GPS-tracking his location for three years, was asked by another guest, the late, lamented Karen Spärck Jones, if he wasn’t bothered by the way this compromised his privacy. He replied in the negative because he had “nothing to hide”. There then followed two hours of vigorous argument which touched on, among other things, the naivete of geeks, the ease with which the punctiliousness of Dutch bureaucracy made it easy to round up Dutch Jews after the Germans invaded Holland in the Second World War, the uses to which location data might be put by unsavoury characters and governments, Karl Popper and the Open Society, etc. etc.

Michael Dales has a couple of interesting blog posts (here and here) about the iPhone data-gathering facility. And, like all geeks, he’s totally unsurprised by the whole affair.

It seems rather than worry geeks, most of us find the data amazing. I suspect that’s because most of us know that this data could be got otherhow anyway – all it really shows is where your phone has been, and the phone operators know that anyway – and I typically trust them a lot less than I trust Apple (not that I think Apple is angelic, it’s a shareholder owned company, but I generally have a more antagonistic relationship with phone companies than I do Apple). So the fact the data resides on my phone is handy – if I was worried about people tracking where my phone goes then I’d never turn it on.

Michael also sees positive angles to this.

If you have a Mac and want to see where your iPhone has been (and then, like most people, post it to the Internet :) then you can get the tool to do so here. What I think is potentially really exciting is what you can do with the data now that you have access to it, not just your phone company. Quentin has already had the idea that you could use it to geotag your photos, which would be awesome, but how about things like carbon calculators, trip reports, and so on?

This post attracted a useful comment from ScaredyCat which gets to the heart of the problem:

The brouhaha isn’t just about the data being stored, it’s about the data being stored unencrypted. I love data like any geek but you do have to wonder why the data is being collected in the first place.

Precisely. What the data-logging and storage facility means is that your iPhone is potentially a source of useful confidential information for people who would have no hope of obtaining that information legally from a mobile phone network.

This point is neatly encapsulated by Rory Cellan-Jones in his blog post:

This obviously has intriguing implications for anyone who possesses one of these devices. What, for instance, if you had told your wife that you were off on a business trip – when in fact you had slipped off to the slopes with some mates – and she then managed to track down your iPhone location file? (I should stress that this is an imaginary scenario).

For divorce lawyers, particularly in the United States, the first question when taking on a new client could be “does your spouse own an iPhone?” And law enforcement agencies will also be taking a great interest in the iPhones – or iPads – of anyone they are tracking.

The other interesting thing about the spyPhone story is that, according to Alex Levinson, it’s an old story. He says that

Back in 2010 when the iPad first came out, I did a research project at the Rochester Institute of Technology on Apple forensics. Professor Bill Stackpole of the Networking, Security, & Systems Administration Department was teaching a computer forensics course and pitched the idea of doing forensic analysis on my recently acquired iPad. We purchased a few utilities and began studying the various components of apple mobile devices. We discovered three things:

* Third Party Application data can contain usernames, passwords, and interpersonal communication data, usually in plain text.

* Apple configurations and logs contain lots of network and communication related data.

* Geolocational Artifacts were one of the single most important forensic vectors found on these devices.After presenting that project to Professor Stackpole’s forensic class, I began work last summer with Sean Morrissey, managing director of Katana Forensics on it’s iOS Forensic Software utility, Lantern. While developing with Sean, I continued to work with Professor Stackpole an academic paper outlining our findings in the Apple Forensic field. This paper was accepted for publication into the Hawaii International Conference for System Sciences 44 and is now an IEEE Publication. I presented on it in January in Hawaii and during my presentation discussed consolidated.db and it’s contents with my audience – my paper was written prior to iOS 4 coming out, but my presentation was updated to include iOS 4 artifacts.

Thanks to David Smith for passing on the link to the Levinson post.