As I observed the other day, one of the things that drove me to write From Gutenberg to Zuckerberg was exasperation at the number of people who thought the Web is the Internet. In lecturing about this I developed a provocative trope in which I said that, although the Web is huge, in 50 years time we may see it as just a blip in the evolution of the Net. This generally produced an incredulous reaction.

So it’s interesting to see Joe Hewitt arguing along parallel lines. Unlike me, he suggests a process by which the Web might be sidelined. “The arrogance of Web evangelists is staggering”, he writes.

They take for granted that the Web will always be popular regardless of whether it is technologically competitive with other platforms. They place ideology above relevance. Haven’t they noticed that the world of software is ablaze with new ideas and a growing number of those ideas are flat out impossible to build on the Web? I can easily see a world in which Web usage falls to insignificant levels compared to Android, iOS, and Windows, and becomes a footnote in history. That thing we used to use in the early days of the Internet.

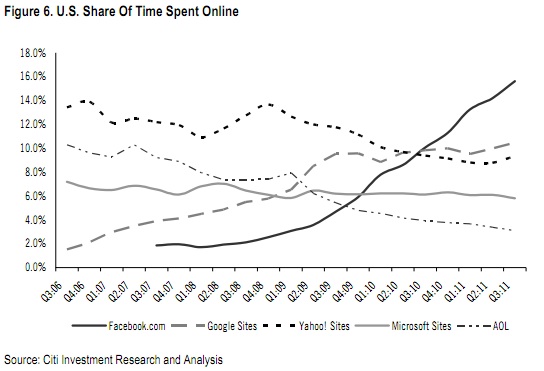

My prediction is that, unless the leadership vacuum is filled, the Web is going to retreat back to its origins as a network of hyperlinked documents. The Web will be just another app that you use when you want to find some information, like Wikipedia, but it will no longer be your primary window. The Web will no longer be the place for social networks, games, forums, photo sharing, music players, video players, word processors, calendaring, or anything interactive. Newspapers and blogs will be replaced by Facebook and Twitter and you will access them only through native apps. HTTP will live on as the data backbone used by native applications, but it will no longer serve those applications through HTML. Freedom of information may be restricted to whatever our information overlords see fit to feature on their App Market Stores.

I hope he’s wrong and given that he’s a serious and successful Apps developer he has an axe to grind. But his blog makes one think…