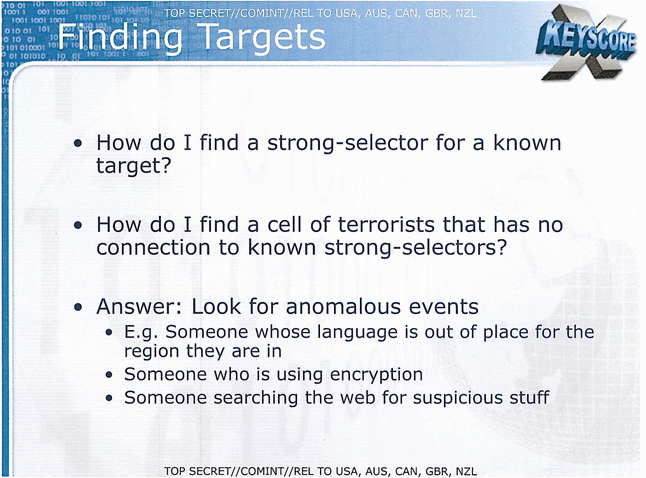

I’m not sure that this slide from the XKeyscore slide deck revealed by the Guardian has received the attention it deserves.

It says that one of the “anomalous” factors an NSA analyst might look for when deciding whether to drill down on someone is whether or not the person is using encryption (like PGP).

So… you can be a perfectly innocent, nay admirable, person like, say, Cory Doctorow, who encrypts his email simply to ensure that only he and the recipient can read it. But that fact alone might be sufficient to start an NSA check on all your communications.

This is one reason why the adjective “Orwellian” isn’t adequate for describing the mess we’re in. “Kafkaesque” is, if anything, even more apt.