This morning’s Observer column.

Sooner or later, every argument about regulation of the internet comes down to the same question: is this the thin end of the wedge or not? We saw a dramatic illustration last week when the European court of justice handed down a judgment on a case involving a Spanish lawyer, one Mario Costeja González, who objected that entering his name in Google’s search engine brought up embarrassing information about his past (that one of his properties had been the subject of a repossession)…

Read on

LATER

Three interesting — and usefully diverse — angles on the ECJ decision.

- Daithi Mac Sitigh points out that the decision highlights the tensions between EU and US law. “This is particularly significant”, he says, “given that most of the major global players in social networking and e-commerce operate out of the US but also do a huge amount of business in Europe.”

Google’s first line of defence was that its activities were not subject to the Data Protection Directive. It argued that its search engine was not a business carried out within the European Union. Google Spain was clearly subject to EU law, but Google argued that it sells advertising rather than running a search engine.

The court was asked to consider whether Google might be subject to the Directive under various circumstances. A possible link was the use of equipment in the EU, through gathering information from EU-based web servers or using relevant domain names (such as google.es). Another suggestion was that a case should be brought at its “centre of gravity”, taking into account where the people making the requests to delete data have their interests.

But the court never reached these points. Instead, it found the overseas-based search engine and the Spain-based seller of advertising were “inextricably linked”. As such, Google was found to be established in Spain and subject to the directive.

The message being sent was an important one. Although this ruling is specific to the field of data protection, it suggests that if you want to do business in the EU, a corporate structure that purports to shield your activities from EU law will not necessarily protect you from having to comply with local legislation. This may explain the panicked tone of some of the reaction to the decision.

- In an extraordinary piece, “Right to Forget a Genocide”, Zeynep Tufekci muses about how (Belgian) colonial imposition of ID cards on Rwandan citizens was instrumental in facilitating genocide.

It may seem like an extreme jump, from drunken adolescent photos to genocide and ethnic cleansing, but the shape, and filters, of a society’s memory is always more than just about individual embarrassment or advancement. What we know about people, and how easily we can identify or classify them, is consequential far beyond jobs and dates, and in some contexts may make the difference between life and death.

“Practical obscurity”—the legal term for information that was available, but not easily—has died in most rich countries within just about a decade. Court records and criminal histories, which were only accessible to the highly-motivated, are now there at the click of a mouse. Further, what is “less obscure” has greatly expanded: using our online data, algorithms can identify information about a person, such as sexual orientation and political affiliation, even if that person never disclosed them.

In that context, take Rwanda, a country many think about in conjunction with the horrific genocide 20 years ago during which more than 800,000 people were killed—in just about one hundred days. Often, stories of ethnic cleansing and genocide get told in a context of “ancient hatreds,” but the truth of it is often much uglier, and much less ancient. It was the brutal colonizer of Rwanda, Belgium, that imposed strict ethnicity-based divisions in a place where identity tended to be more fluid and mixed. Worse, it imposed a national ID system that identified each person as belonging to Hutu, Tutsi or Twa and forever freezing them in that place. [For a detailed history of the construction of identity in Rwanda read this book, and for the conduct of colonial Belgium, Rwanda’s colonizer, read this one.]

Few years before the genocide, some NGOs had urged that Rwanda “forget” ethnicity, erasing them from ID cards.

They were not listened to.

During the genocide, it was those ID cards that were asked for at each checkpoint, and it was those ID cards that identified the Tutsis, most of whom were slaughtered on the spot. The ID cards closed off any avenue of “passing” a checkpoint. Ethnicity, a concept that did not at all fit neatly into the region’s complex identity configuration, became the deadly division that underlined one of the 20th century’s worst moments. The ID cards doomed and fueled the combustion of mass murder.

- Finally, there’s a piece in Wired by Julia Powles arguing that “The immediate reaction to the decision has been, on the whole, negative. At best, it is reckoned to be hopelessly unworkable. At worst, critics pan it as censorship. While there is much to deplore, I would argue that there are some important things we can gain from this decision before casting it roughly aside.”

What this case should ideally provoke is an unflinching reflection on our contemporary digital reality of walled gardens, commercial truth engines, and silent stewards of censorship. The CJEU is painfully aware of the impact of search engines (and ‘The’ search engine, in particular). But we as a society should think about the hard sociopolitical problems that they pose. Search engines are catalogues, or maps, of human knowledge, sentiments, joys, sorrows, and venom. Silently, with economic drivers and unofficial sanction, they shape our lives and our interactions.

The fact of the matter here is that if there is anyone that is up to the challenge of respecting this ruling creatively, Google is. But if early indications are anything to go by, there’s a danger that we’ll unwittingly save Google from having to do so, either through rejecting the decision in practical or legal terms; through allowing Google to retreat “within the framework of their responsibilities, powers and capabilities” (which could have other unwanted effects and unchecked power, by contrast with transparent legal mechanisms); or through working the “right to be forgotten” out of law through the revised Data Protection Regulation, all under the appealing but ultimately misguided banner of preventing censorship.

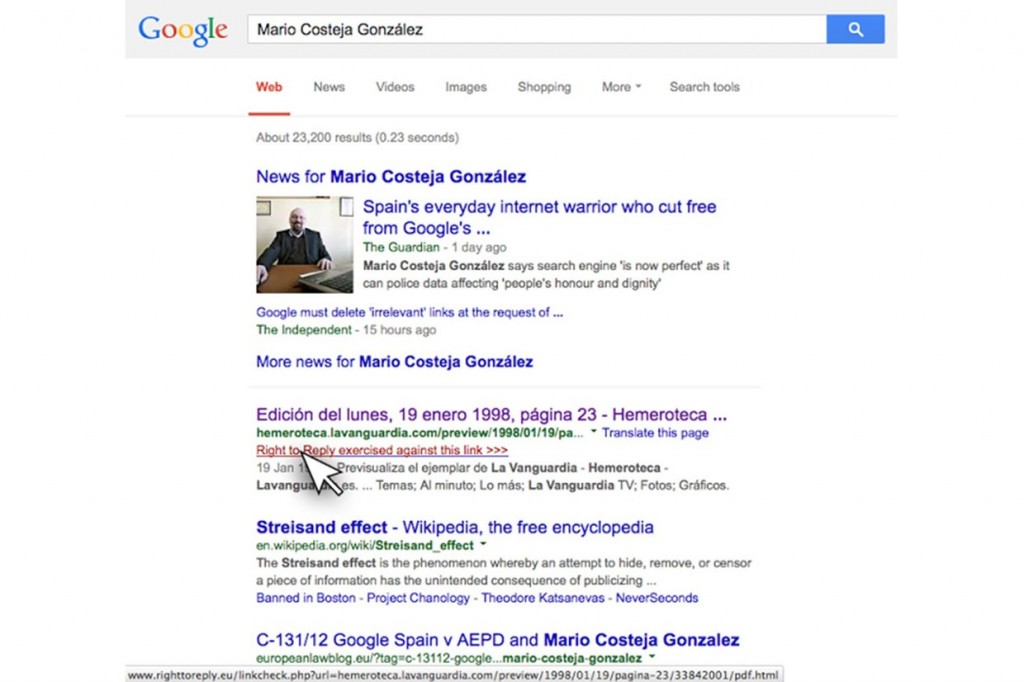

There is, Powles argues, a possible technical fix for this — implementation of a ‘right to reply’ in search engine results.

An all-round better solution than “forgetting”, “erasure”, or “take-down”, with all of the attendant issues with free speech and the rights of other internet users, is a “right to reply” within the notion of “rectification”. This would be a tech-enabled solution: a capacity to associate metadata, perhaps in the form of another link, to any data that is inaccurate, out of date, or incomplete, so that the individual concerned can tell the “other side” of the story.

We have the technology to implement such solutions right now. In fact, we’ve done a mock-up envisaging how such an approach could be implemented.

Search results could be tagged to indicate that a reply has been lodged, much as we see with sponsored content on social media platforms. Something like this, for example:

(Thanks to Charles Arthur for the Tufekci and Powles links.)

of Walter Benjamin