… were a few of the topics covered when I was interviewed by Tim Garton-Ash at the European Studies Centre in St Antony’s College, Oxford in February.

What the election ought to be about

“The political problem of mankind is to combine three things: economic efficiency, social justice and individual liberty. The first needs criticism, precaution and technical knowledge; the second, an unselfish and enthusiastic spirit, which loves the ordinary man; the third, tolerance, breadth, appreciation of the excellencies of variety and independence, which offers above everything, to give unhindered opportunity to the exceptional and the aspiring.”

John Maynard Keynes, Collected Works, Vol IX, p. 311.

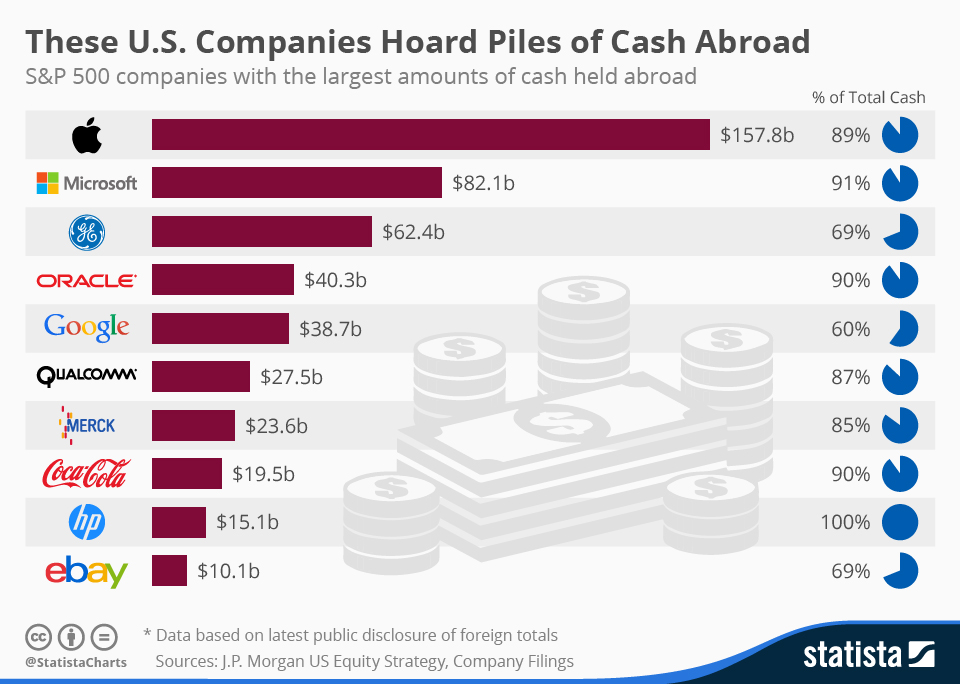

So who are the biggest hoarders of cash overseas?

The system failed. It happens, even in Germany

From today’s New York Times:

BERLIN — Even in the nightmarish immediate aftermath of the plane crash in the French Alps on Tuesday, Carsten Spohr, the former pilot who runs Germany’s Lufthansa airline, was sure of one thing: the co-pilot, Andreas Lubitz, 27, was “100 percent” fit to fly.

Mr. Lubitz, after all, had been through the widely respected Lufthansa training system — “one of the best in the world,” Mr. Spohr said — and had met all other requirements to fly commercial aircraft.

In the decades since it emerged from the ruins of Nazism, this country — which reunited in 1990 and in recent years has dominated Europe as its economic powerhouse — has come to define itself as orderly, rule-driven and well-engineered. It is an identity that is both an antidote to its past and a blueprint for economic success. From Mercedes-Benz cars — “the best,” says a current ad campaign — to its countless tidy towns, Germany purrs excellence.

Now Mr. Lubitz — born and raised in one of those pretty towns — has upended that well-ordered world and challenged other assumptions built into German life. As Mr. Spohr noted, the co-pilot’s terrifying deed was a singular, perhaps unstoppable disaster. Yet somehow the system failed.

Sure, it did. Systems do. Even in Germany.

The process, not the product, matters

Almost all the (mostly feverish) discussion about Apple focusses on its astonishing mastery of product design. But this week’s Monday Note by Jean-Louis Gasseé has made me reflect on what is actually the most remarkable aspect of the company, namely the fact that it has mastered what must be the most complex, large-scale, precision manufacturing process in industrial history.

In his Note, Jean-Louis leans heavily not only on Greg Koenig’s fascinating analysis of the process by which the iWatch is being made, but also on Koenig’s observation that

“Apple is the world’s foremost manufacturer of goods. At one time, this statement had to be caged and qualified with modifiers such as “consumer goods” or “electronic goods,” but last quarter, Apple shipped a Boeing 787’s weight worth of iPhones every 24 hours. When we add the rest of the product line to the mix, it becomes clear that Apple’s supply chain is one of the largest scale production organizations in the world.”

When you think of it in those terms, it’s clear that in our obsession with the beauty of Apple designs we may have been missing the really big picture, which is that the company has been building a production system that could eventually yield astonishing benefits and change the way every tech manufacturer operates.

We’ve been here before, by the way. When the Japanese first began making cars, they were ridiculed by Western manufacturers — for good reasons. They were clunky, ugly and they rusted early. But the Japanese were good at learning from mistakes. They also sussed that if they were to make really good cars, they had to reinvent the process by which cars were made. From this came the Toyota ‘Lean Machine’ production process, which is now how all cars, everywhere, are made.

So the process is often more important than the product. This was also the point made by Steven weber years ago, in his splendid book about open source software. It’s a distinctive way of making incredibly complex products. In fact, it may ultimately be the only way of making really secure software.

Gasseé’s conclusion from his meditations is that it would now be foolish to discount rumours that Apple is planning to manufacture cars. I agree.

Facebook: the unique self-disrupting machine?

Interesting post by M.G. Siegler:

Reading over the coverage of F8 this week, one thing is clear: Facebook the social network isn’t very interesting anymore. I think we’re on the other side of its peak, even if we can’t perceive that just yet. The interesting parts of Facebook are now Messenger, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Oculus.

They are slowly becoming Facebook. A federation of products, not the social networking stream.

I think we’ll look back and believe that Facebook, like Apple, is a company that did a great job disrupting itself before others could. And they did it all through smart acquisitions — people forget that even Messenger was an acquisition way back when. Just imagine if they had been able to buy Snapchat as well…

Crime doesn’t pay, unless it’s online

This morning’s Observer column:

Now I know that there are lies, damned lies and crime statistics, but everyone in the UK, including the Office for National Statistics, seems to agree that recorded crime is decreasing – and has been for quite a while. This is one of the arguments the government is using to justify its savage cuts in police budgets. Given that we’ve got crime on the run (so the argument goes) all we have to do now is to get the coppers to become more efficient – working smarter, making better use of information technology and computers, etc. Reduction in crime means we don’t need so many police officers. QED.

The only fly in this rosy ointment is that it’s based on a false premise. Recorded crime is declining, but that’s largely due to the fact that crime has moved on – specifically from the physical world to cyberspace. And there’s a very simple reason for this: cybercrime is a much safer and more lucrative activity than its real-world counterpart. The rewards are much greater, and the risks of being caught and convicted are vanishingly small. So if you’re a rational criminal with a reasonable IQ, why would you bother mugging people, breaking into houses, nicking cars and doing all the other things that old-style crooks do – and that old-style cops are good at catching them doing?

The fightback begins here

At last!

After Nigel Farage’s exclusion from a television programme and the assassination of Jeremy Clarkson, elections have been suspended and traditional British common sense has been classed as hate speech.

Toynbee said: “We namby-pambies, we do-gooders, we pinkos have emerged from our ivory towers and hypocritically large houses to fill the power vacuum left by the downfall of the Chipping Norton set.

“From now on, you think only what our think-pieces tell you to think.”

Resistance leaders Rod Liddle and Peter Hitchens have gone underground using a secret network of national newspapers to continue bravely saying the things they say they are not allowed to say.

Alas, only a spoof

The Cameron-Blair nexus

Who owns your data? Hint: not you

Nice video from Jon Crowcroft and his colleagues on the HAT Project.