Wired nails it

But this isn’t about unlocking a phone; rather, it’s about ordering Apple to create a new software tool to eliminate specific security protections the company built into its phone software to protect customer data. Opponents of the court’s decision say this is no different than the controversial backdoor the FBI has been trying to force Apple and other companies to build into their software—except in this case, it’s an after-market backdoor to be used selectively on phones the government is investigating.

The stakes in the case are high because it draws a target on Apple and other companies embroiled in the ongoing encryption/backdoor debate that has been swirling in Silicon Valley and on Capitol Hill for the last two years. Briefly, the government wants a way to access data on gadgets, even when those devices use secure encryption to keep it private.

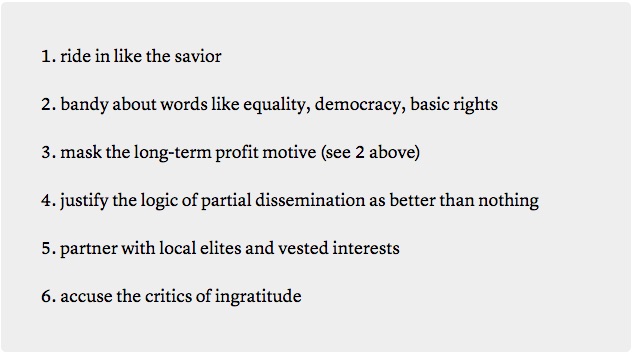

Yep. This is backdoor so by another route. It’s also forcing a company to do work for the government that, in this case, the government wants to do but claims it can’t. This will play big in China, Russia, Bahrain, Iran and other places too sinister to mention.

The FBI’s argument that the phone is vital for its investigation Seems weak. They already know everything they need to know, and the idea that the San Bernardino killers were serious ISIS stooges seems the prevalence of mass shootings in the US, and the say they conformed to type. What’s more likely is that the agency is playing politics. They’ve been arguing for yonks that they simply must have back doors. The San Bernardino killers presented them with a heaven-sent opportunity to leverage public outrage to force a tech company into conceding the backdoor principle.