Street scene, Cambridge, February 2016.

Weathered

Going Dark? Dream on.

This morning’s Observer column:

The Apple v FBI standoff continues to generate more heat than light, with both sides putting their case to “the court of public opinion” — which, in this case, is at best premature and at worst daft. Apple has just responded to the court injunction obliging it to help the government unlock the iPhone used by one of the San Bernadino killers with a barrage of legal arguments involving the first and fifth amendments to the US constitution. Because the law in the case is unclear (there seems to be only one recent plausible precedent and that dates from 1977), I can see the argument going all the way to the supreme court. Which is where it properly belongs, because what is at issue is a really big question: how much encryption should private companies (and individuals) be allowed to deploy in a networked world?

In the meantime, we are left with posturing by the two camps, both of which are being selective with the actualité, as Alan Clark might have said…

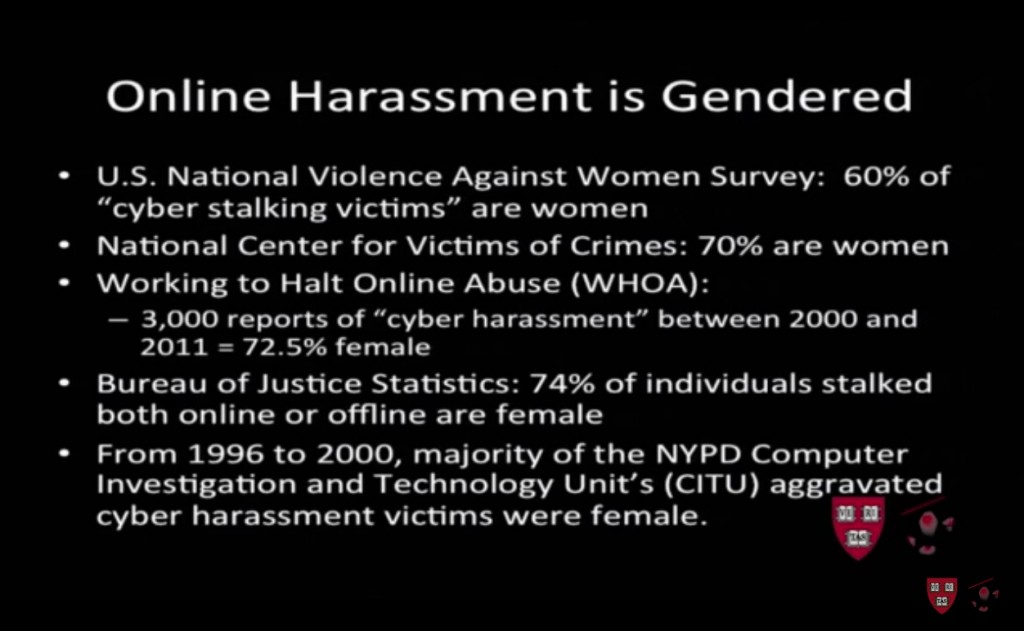

The misogynistic Internet

From Sarah Jeong’s Berkman lecture on “The Internet of Garbage”.

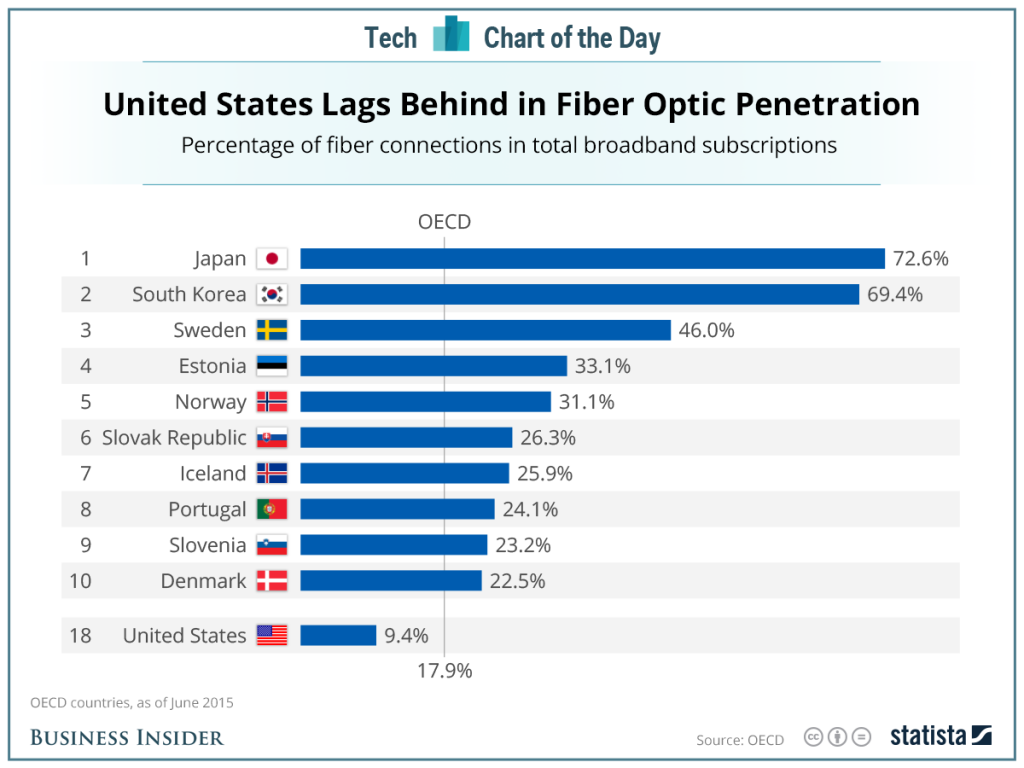

Guess who’s missing

Brexit, 1997-style

This video was, I think, sent to every household in the UK in 1997. It will still resonate with some voters on June 23, I suspect.

Quote of the Day

“This case is like a crazy-hard law school exam hypothetical in which a professor gives students an unanswerable problem just to see how they do.”

Law Professor Orin Kerr, in a thoughtful and informative article on the dispute between Apple and the FBI over the San Bernardino killer’s iPhone 5.

Orion mission re-ignites moon landing conspiracy theories

Orion is NASA’s next-generation spacecraft, “built to take astronauts deeper into space than we’ve ever gone before”. The video was made to highlight the complexity of the design challenges, particularly the amount of protection needed to safeguard fragile equipment and astronauts as the craft hurtles through the Van Allen radiation belt. “Radiation like this could harm the guidance systems, on-board computers or other electronics on Orion,” says the personable narrator. “Shielding will be put to the test as the vehicle cuts through the waves of radiation… We must solve these challenges before we send people through this region of space.”

Aha! Cue moon landing conspiracy theorists. “If the moon missions were real”, says one then it seems the whole ‘punching through the Van Allen belt’ problem should have been solved over 40 years ago.”

Sadly, the problem wasn’t solved then. The Apollo astronauts were pushed through the belt on their way to the moon and back, on the basis that their exposure was brief and the amount of radiation they received was below the dose allowed by US law for workers in nuclear power stations.

Sigh. The “slaughter of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact”, as TH Huxley used to say.

Lazy days

Killer Apps?

This morning’s Observer column:

“Guns don’t kill people,” is the standard refrain of the National Rifle Association every time there is a mass shooting atrocity in the US. “People kill people.” Er, yes, but they do it with guns. Firearms are old technology, though. What about updating the proposition from 1791 (when the second amendment to the US constitution, which protects the right to bear arms, was ratified) to our own time? How about this, for example: “algorithms kill people”?

Sounds a bit extreme? Well, in April 2014, at a symposium at Johns Hopkins University, General Michael Hayden, a former director of both the CIA and the NSA, said this: “We kill people based on metadata”. He then qualified that stark assertion by reassuring the audience that the US government doesn’t kill American citizens on the basis of their metadata. They only kill foreigners…

LATER In the column I discuss the decision-making process that must go on in the White House every Tuesday (when the kill-list for drone strikes is reportedly decided). This afternoon, I came on this account of the kind of conversation that goes on in Washington (possibly in the White House) when deciding whether to launch a strike:

“ARE you sure they’re there?” the decision maker asks. “They” are Qaeda operatives who have been planning attacks against the United States.

“Yes, sir,” the intelligence analyst replies, ticking off the human and electronic sources of information. “We’ve got good Humint. We’ve been tracking with streaming video. Sigint’s checking in now and confirming it’s them. They’re there.”

The decision maker asks if there are civilians nearby.

“The family is in the main building. The guys we want are in the big guesthouse here.”

“They’re not very far apart.”

“Far enough.”

“Anyone in that little building now?”

“Don’t know. Probably not. We haven’t seen anyone since the Pred got capture of the target. But A.Q. uses it when they pass through here, and they pass through here a lot.”

He asks the probability of killing the targets if they use a GBU-12, a powerful 500-pound, laser-guided bomb.

“These guys are sure dead,” comes the reply. “We think the family’s O.K.”

“You think they’re O.K.?”

“They should be.” But the analyst confesses it is impossible to be sure.

“What’s it look like with a couple of Hellfires?” the decision maker asks, referring to smaller weapons carrying 20-pound warheads.

“If we hit the right room in the guesthouse, we’ll get the all bad guys.” But the walls of the house could be thick. The family’s safe, but bad guys might survive.

“Use the Hellfires the way you said,” the decision maker says.

Then a pause.

“Tell me again about these guys.”

“Sir, big A.Q. operators. We’ve been trying to track them forever. They’re really careful. They’ve been hard to find. They’re the first team.”

Another pause. A long one.

“Use the GBU. And that small building they sometimes use as a dorm …”

“Yes, sir.”

“After the GBU hits, if military-age males come out …”

“Yes, sir?”

“Kill them.”

Less than an hour later he is briefed again. The two targets are dead. The civilians have fled the compound. All are alive.

Ok. You think I made that up. Well, I didn’t. The author is General Michael Hayden, who was director of the Central Intelligence Agency from 2006 to 2009. He is the author of the forthcoming book, Playing to the Edge: American Intelligence in the Age of Terror, from which (I’m guessing) the New York Times piece is taken.