In October last year, my colleague David Runciman wrote a sobering piece in the Guardian under the headline “How the education gap is tearing politics apart”. His starting point was an observation in The Atlantic in March 2015 that the best single predictor of Trump support in the Republican primary was the absence of a college degree.

“The possibility that education has become a fundamental divide in democracy”, he wrote,

with the educated on one side and the less educated on another – is an alarming prospect. It points to a deep alienation that cuts both ways. The less educated fear they are being governed by intellectual snobs who know nothing of their lives and experiences. The educated fear their fate may be decided by know-nothings who are ignorant of how the world really works. Bringing the two sides together is going to be very hard. The current election season appears to be doing the opposite.

Trump continues to poll far ahead of Clinton among voters who did not go to college, while Clinton still leads by a considerable margin among college graduates. This is a significant change from 2012, when the picture was far more mixed. Four years ago, the college-educated vote was almost evenly split, with graduates favouring Obama over Romney by a narrow margin, 50 to 48. Recent polling puts Trump’s lead over Clinton among white men without a college degree at a sobering 76 to 19.

Turning then to Brexit, David observed that:

Voters with postgraduate qualifications split 75 to 25 in favour of remain. Meanwhile, among those who left school without any qualifications, the vote was almost exactly reversed: 73 to 27 for leave. A report from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation last month confirmed that “educational opportunity was the strongest driver” of the Brexit vote. Again, there were plenty of other factors at work – including a significant generational divide. Older voters were far more likely to vote leave, which partly helps to explain the education gap, since the rapid expansion of higher education in recent decades means older voters are also much less likely to have attended university. But the Rowntree report concludes that educational experience was the biggest single determinant of how people voted. Class still matters. Age still matters. But education appears to matter more.

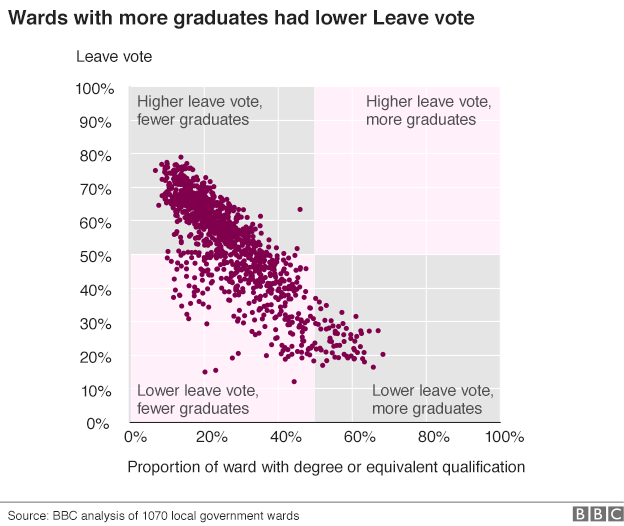

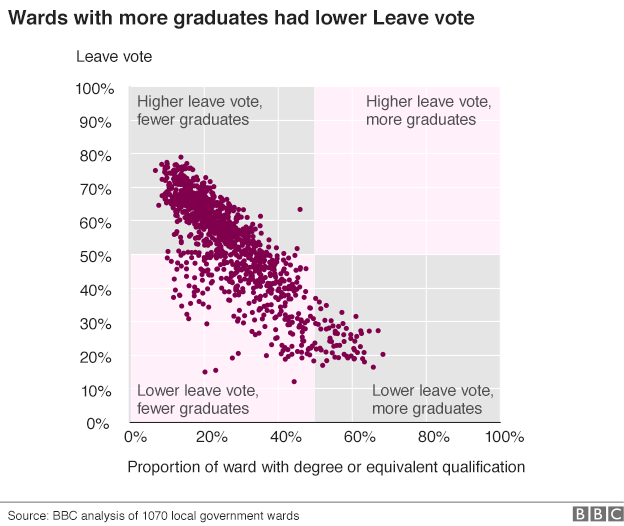

Now from the BBC comes a more localised breakdown of votes from nearly half of the local authorities which counted EU referendum ballots last June. Among the findings are:

-

Confirmation that local results were strongly associated with the educational attainment of voters – populations with lower qualifications were significantly more likely to vote Leave. (The data for this analysis comes from one in nine wards); and

-

The level of education had a higher correlation with the voting pattern than any other major demographic measure from the census.

And if you wanted a vivid graph of this, here’s the correlation diagram:

This is really sobering stuff. It shows, in a picture, why a failure to invest in education and tackle educational underachievement eventually imposes massive social costs (possibly including the breakdown of democracy). It’s not rocket science, either. In an information economy, people who are poorly educated are always going to find it hard to find employment. And when they do it will be in precarious, exploitative, under-paid jobs. No wonder they voted the way they did — for the first charlatan who came along and said he could fix it.