From a remarkable Aeon essay on ‘extremophiles’ (creatures that can survive in extreme conditions) by the evolutionary biologist David Barash:

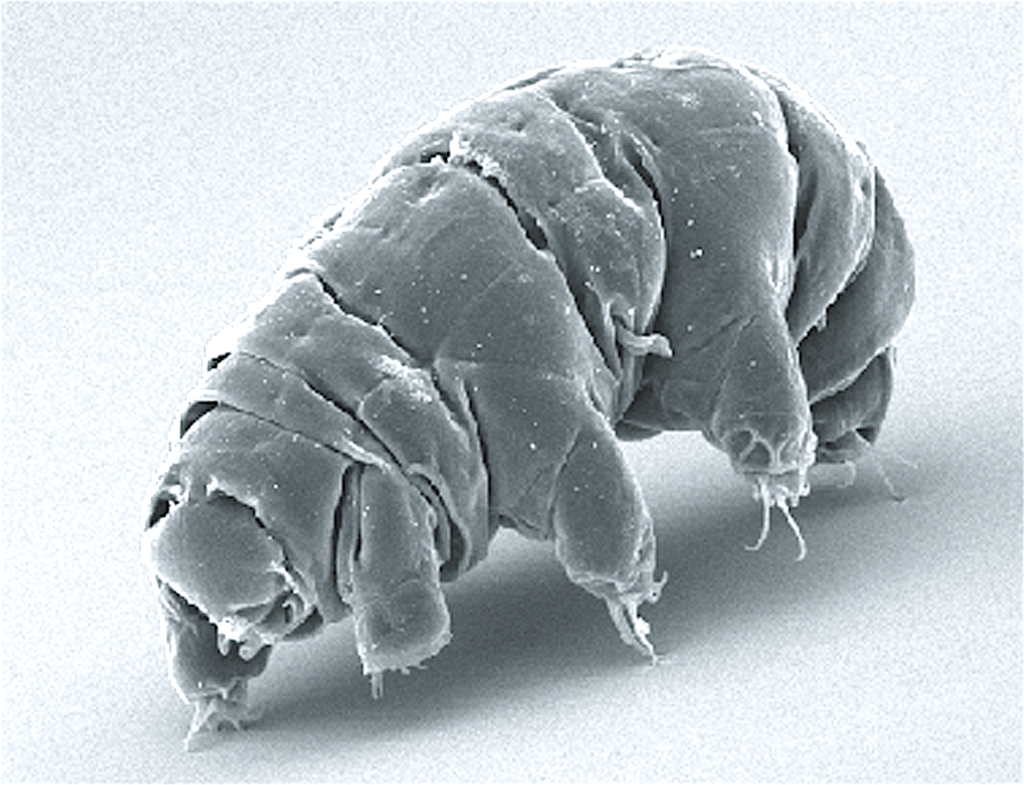

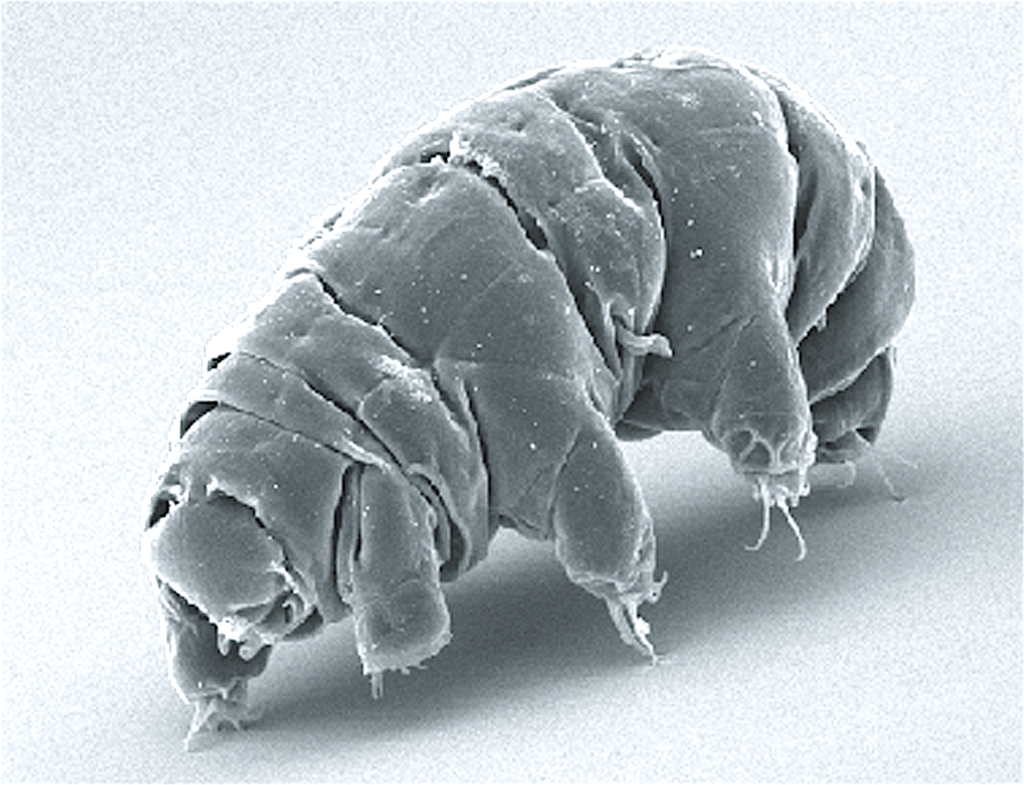

Typical extremophiles specialise in going about their lives along one axis of environmental extremity – extreme heat or cold, one or another heavy metal, and so forth – tardigrades can survive when things get dicey along many different and seemingly independent dimensions, simultaneously and come what may. You can boil them, freeze them, dry them, drown them, float them unprotected in space, expose them to radiation, even deprive them of nourishment – to which they respond by shrinking in size. These creatures, also known as water bears, are featured on appealing T-shirts with the slogan ‘Live Tiny, Die Never’ and in the delightful rap song that describes their indifference to extreme situations, entitled Water Bear Don’t Care.

Tardigrades might be the toughest creatures on Earth. You can put them in a laboratory freezer at -80 degrees Celsius, leave them for several years, then thaw them out, and just 20 minutes later they’ll be dancing about as though nothing had happened. They can even be cooled to just a few degrees above absolute zero, at which atoms virtually stop moving. Once thawed out, they move around just fine. (Admittedly, they aren’t speed demons; the word ‘tardigrade’ means ‘slow walker’.) Exposed to superheated steam – 140 degrees Celsius – they shrug it off and keep on living. Not only are tardigrades remarkably resistant to a wide range of what ecologists term environmental ‘insults’ (heat, cold, pressure, radiation, etc), they also have a special trick up their sleeves: when things get really challenging – especially if dry or cold – they convert into a spore-like form known as a ‘tun’. A tun can live, if you call their unique form of suspended animation ‘living’, for decades, possibly even centuries, and thereby survive pretty much anything that nature might throw at them. In this state, their metabolism slows to less than 0.01 per cent of normal. Compared with them, a deeply hibernating mammal is living at lightning speed.

In the bad old days of the Cold War, we used to think that the only living things that would survive a nuclear holocaust would be beetles. Now that we are headed for a climate catastrophe, my money’s on the tardigrades.