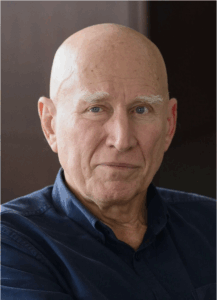

Back in the day

Irish writers Patrick Kavanagh (left) and Anthony Cronin in Dublin on June 16, 1954 preparing for the first public celebration of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

I was born in a country whose religious and civic establishments mostly regarded James Joyce, not as a pioneering modernist writer, but as “a filthy pornographer”. In 1954, the 50th anniversary of the day on which all the action in the novel takes place, a group of distinguished Irish writers decided that they had had enough of this philistinic nonsense. They rented a couple of antique horse-drawn cabs and staged a reenactment of the part of the novel in which Leopold Bloom and his friends drive to Paddy Dignam’s funeral.

Thus was born Bloomsday, which has, er, blossomed into a worldwide celebration of the day. In the 1980s, appalled that a literary city like Cambridge studiously ignored the great day, I decided to host a lunch at which participants would read passages from the novel and have the same lunch that Leopold Bloom enjoyed in Davey Byrne’s pub, namely a glass of Burgundy and a gorgonzola sandwich. And I’ve done that ever since.

Which of course reminds me of an ancient Irish joke:

First man: “Do you like gorgonzola?” Second man: “No, but I hear that his brother Émile is a bloody fine novelist.”

Quote of the Day

”What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

- Joseph Weizenbaum, on discovering how his ‘Eliza’ program (written in 1996) seemed to seduce some of its users, or at any rate imbued the program with human qualities.

And guess what: AI Chatbots are even more persuasive than Eliza. Which is why they are worrying tools for spreading misinformation.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Enya | I dreamt I dwelled in Marble Halls

An unusual and striking rendering of a song that was popular in Joyce’s own day.

Long Read of the Day

Bloomsday Explained

Lovely Paris Review essay by Jonathan Goldman.

“Bloomsday,” the James Joyce scholar Robert Nicholson once quipped, “has as much to do with Joyce as Christmas has to do with Jesus.” The celebrations of Ulysses every June 16—the date on which the novel is set—attract extreme ends of the spectrum of literary enthusiasm. Academics and professionals mingle with obsessives and cranks, plus those simply along for the ride. The event can be stately and meticulous or raucous and chaotic—or, somehow, all of the above.

A telling instance came a few years ago, when the Irish Arts Center arranged a Bloomsday picnic in New York’s Bryant Park, under the rueful shadow of the Gertrude Stein statue. (Stein disliked Joyce.) Aspiring Broadway types were enlisted to circulate in period costume before bursting into popular songs from 1900-era Ireland. I spoke to one of the performers, a young Irish actor who had recently moved to New York. Had she read Ulysses? “I plan to,” she said, and in my memory, she adds, “I’m told it’s a grand book by them that knows.” The kicker was when the Irish finance minister, in town for summit meetings, got up to say that his government would take as inspiration the balanced daily budget that appears in Ulysses. The problem? Leopold Bloom’s spreadsheet in Ulysses works out only because he omits the money he’s paid to Bella Cohen’s brothel. No one pointed out the irony.

The admixture of expertise and fanboyism that marks Bloomsday, perhaps unique among literary gatherings, is remarkable…

It is indeed. And I am guilty as charged. But do read the essay.

So long, Bill Atkinson, and thanks for the epiphany

Yesterday’s Observer column…

I still remember the moment when I first encountered his work – a moment that James Joyce might have described as an epiphany. It was at a workshop for academics in Cambridge organised by Apple UK in 1984 to introduce its new Macintosh computer. In a stuffy conference room were a number of tables on which sat chic, cream-coloured machines with 9in screens and separate keyboards. Each had been set up displaying a picture of a fish, and I remember staring at the image, marvelling at the way the scales and fins seemed as clear as if they had been etched on the screen.

Picking up courage, I clicked on the “lasso” tool and selected a fin with it. The lasso suddenly began to shimmer. I held down the mouse button and moved the rodent gently. The fin began to move across the screen! I pulled down the edit menu and clicked on “cut”. The fin disappeared. Finally, I closed the file and then reloaded it from the disk.

As the edited image reappeared, I had the kind of feeling that Douglas Adams had experienced when he had done the same operation – “that kind of roaring, tingling, floating sensation”, as he put it when talking to US tech journalist Steven Levy. In the blink of an eye, all the Teletypes and dumb terminals and character-based displays that had been defining parts of my experience with computers were consigned to history. I had suddenly seen the point – and the potential – of computer graphics…

So many books, so little time

I’m a sucker for diaries. Always have been. But Alan Clark’s three volumes, of which this is the last, were the best political diaries ever, partly because they were shameless, but also because of how revealing they could be. He was not a nice man: old-fashioned terms ‘cad’ and ‘bounder’ come immediately to mind. But his great saving grace is that he doesn’t seem to have been a hypocrite. When accosted by revelations of appalling behaviour that would have ended any other politician’s career — like the affairs he had with virtually the entire female side of a particular family — he would cheerfully plead guilty as charged. But this cad/bounder, was a dazzling diarist. The writer he most reminded me of was Samuel Pepys, who was also no angel. This final volume goes all the way to Clark’s death from a brain tumour. He kept it going until he could no longer focus on the page. You had to admire him for that alone.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!