A Hollyhock on Brancaster Staithe on a Summer’s evening.

Reflections on the Afghanistan fiasco

- It’s Biden’s Bay of Pigs. That was a botched invasion and Biden’s exit was a botched withdrawal. JFK learned a lot from his fiasco. One wonders what Biden will learn from his.

- It was useful in blowing a gaping hole in British delusions about the UK’s ‘special relationship’ with the US. As Jonty Bloom put it, “The fact that President Biden didn’t even call the British PM before deciding to pull out his troops and let the Taliban take back Afghanistan, tells you a great deal. Decades of supporting the US, the lost lives, maimed soldiers and billions in wasted money has meant nothing to Washington. Sure, it’s nice to be able to say that America is not acting alone but this isn’t a special relationship”.

- Francis Fukuyama pointed out in The Economist that recent events in Kabul are merely a dramatic illustration of a process that has been under way for a while. “The truth of the matter”, he wrote, “is that the end of the American era had come much earlier. The long-term sources of American weakness and decline are more domestic than international. The country will remain a great power for many years, but just how influential it will be depends on its ability to fix its internal problems, rather than its foreign policy.”

- Since the US won’t be able to fix its internal problems, and a Trumpist Republican Party will be back in business after the mid-terms, that means that the rest of the world will have to permanently revise its assumptions about American hegemony. It’ll still be a giant, but an unstable and unreliable one.

- Then there’s the question — rarely asked in polite circles — about whether the US has, on balance, been a force for good in the world. Writing on Project Syndicate today, Jeffrey Sachs lays out the charge-sheet. It’s not pretty:

Almost every modern US military intervention in the developing world has come to rot. It’s hard to think of an exception since the Korean War. In the 1960s and first half of the 1970s, the US fought in Indochina – Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia – eventually withdrawing in defeat after a decade of grotesque carnage. President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Democrat, and his successor, the Republican Richard Nixon, share the blame. In roughly the same years, the US installed dictators throughout Latin America and parts of Africa, with disastrous consequences that lasted decades. Think of the Mobutu dictatorship in the Democratic Republic of Congo after the CIA-backed assassination of Patrice Lumumba in early 1961, or of General Augusto Pinochet’s murderous military junta in Chile after the US-backed overthrow of Salvador Allende in 1973. In the 1980s, the US under Ronald Reagan ravaged Central America in proxy wars to forestall or topple leftist governments. The region still has not healed.

Since 1979, the Middle East and Western Asia have felt the brunt of US foreign policy’s foolishness and cruelty. The Afghanistan war started 42 years ago, in 1979, when President Jimmy Carter’s administration covertly supported Islamic jihadists to fight a Soviet-backed regime. Soon, the CIA-backed mujahedeen helped to provoke a Soviet invasion, trapping the Soviet Union in a debilitating conflict, while pushing Afghanistan into what became a forty-year-long downward spiral of violence and bloodshed. Across the region, US foreign policy produced growing mayhem. In response to the 1979 toppling of the Shah of Iran (another US-installed dictator), the Reagan administration armed Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in his war on Iran’s fledgling Islamic Republic. Mass bloodshed and US-backed chemical warfare ensued. This bloody episode was followed by Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait, and then two US-led Gulf Wars, in 1990 and 2003.

The latest round of the Afghan tragedy began in 2001…

What these cases have in common, Sachs thinks, “is not just policy failure. Underlying all of them is the US foreign-policy establishment’s belief that the solution to every political challenge is military intervention or CIA-backed destabilization”.

Quote of the Day

”Advertising is a racket. Its constructive contribution to society is exactly zero.”

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Beethoven Moonlight Sonata | Horowitz | 1956

Link

Poor audio quality, but lovely.

Long Read of the Day

Against Incrementalism

Martin O’Neill’s interesting and thoughtful review essay in the Boston Review on Ed Miliband’s GO BIG: How to Fix our World.

Miliband’s central argument is that our economic model has become structurally unjustifiable. The centrist attempt—represented in the UK by Blair’s “third way” and its continuation under Brown—to present a softened, humanized version of neoliberal capitalism has been tested to destruction and found to be grossly inadequate. Miliband instead urges an overdue reckoning with the lessons of the Great Financial Crisis, alongside a transformative reworking of the economy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and in the face of the worsening climate crisis. Together these challenges necessitate a radically different politics.

This is a sympathetic but not uncritical piece which suggests that Miliband is a more interesting thinker than many of us had assumed.

The Feds are finally catching up with Musk’s daft Autopilot claims

Vice reports that the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has opened an investigation into 11 cases where a Tesla on Autopilot crashed into emergency vehicles. NHTSA has previously disclosed it is also investigating 30 other Tesla crashes where 10 people died, most involving Autopilot of FSD.

Tesla, the world’s most frustrating company, simultaneously makes what are widely regarded as the best electric vehicles and most functional and comprehensive charging network while also selling the world’s most dangerous and widely abused driver-assist features. Thanks to years of the company’s misleading marketing of the “Autopilot” and “Full Self-Driving” packages—as well as the frequent wild claims by the extremely online CEO Elon Musk such as the prediction in 2019 that there would be one million Tesla robotaxis by 2020 – owners perceive it to be far more capable than it is.

Not this owner, though.

I have a Tesla and any owner who hasn’t been drinking the Musk Kool Aid must know that his claims about Autopilot’s capabilities are overblown. Musk’s suggestions that the vehicle is anywhere near Level 5 autonomy are blatantly false. Autopilot is basically just a superior form of cruise control which can keep the vehicle in its lane on well-marked dual-carriageways or motorways, and sometimes provides useful alerts to the driver. But otherwise it struggles with normal English roads: it’s continually baffled by traffic islands on single carriageways, for example.

Don’t get me wrong. The Model 3 is a fine car. It’s quiet, agile and responsive — and as fast as a high-end conventional Porsche if you want to use the available power. (Zero to 60 in 3.1 seconds.) It’s also very cheap to run (once you’ve paid for it). Charge it overnight at home on a night-time tariff with electricity from renewable sources and the ‘fuel’ cost is about 1.5p/mile. And it requires very little maintenance compared to an ICE vehicle. Think of it as software with wheels — which means that bugs get fixed quickly and there are constant upgrades.

We also find it more restful on long journeys, which may be a result of the much quieter cabin. But it won’t be driving itself anytime soon.

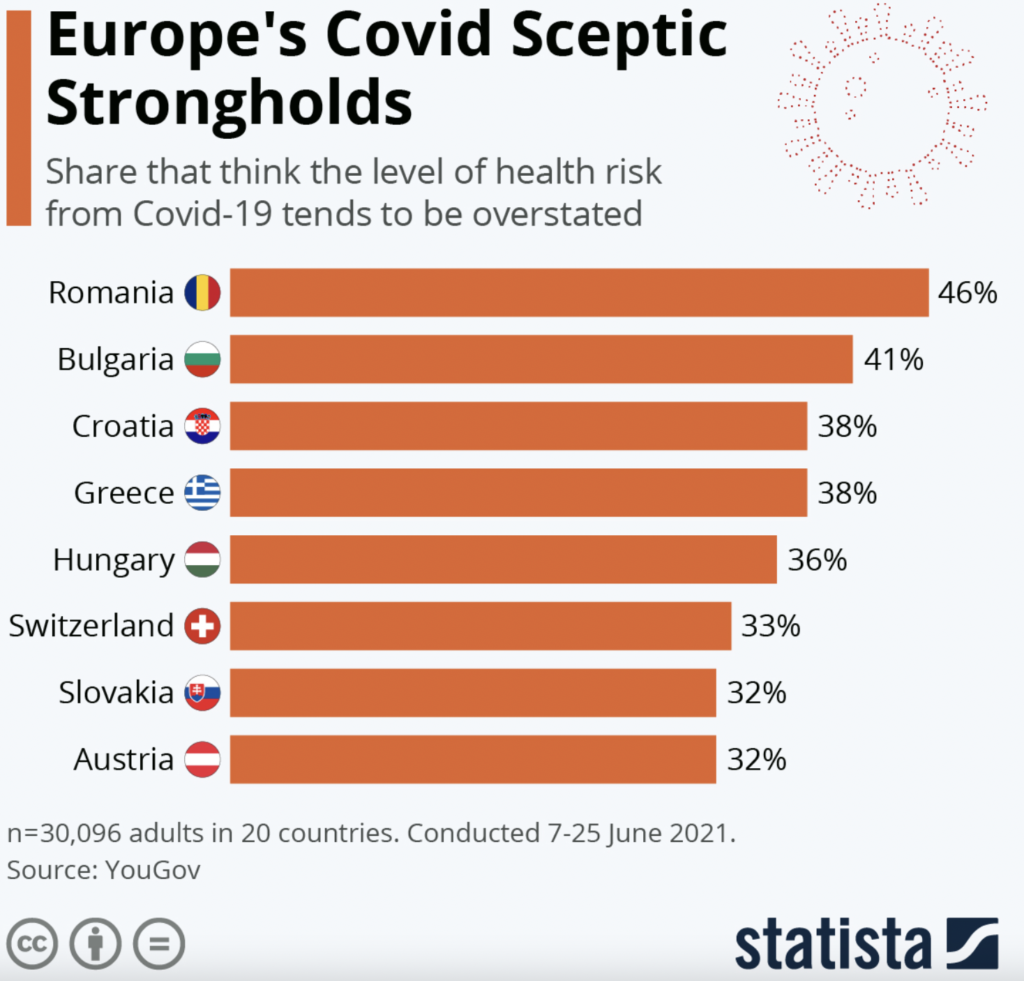

Chart of the Day

This blog is also available as a daily newsletter. If you think this might suit you better why not sign up? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-button unsubscribe if you conclude that your inbox is full enough already!