Quote of the Day

”War is the unfolding of miscalculations.”

- Barbara Tuchman

(Who is my favourite writer of popular history)

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Van Morrison | Days Like This

Something to play while queuing for petrol.

Long Read of the Day

On the Downfalls of Progress and the Utopian Promise of Fueled Abundance

This is wonderful — a long excerpt from Alice Bell’s book, Our Biggest Experiment: A History of the Climate Crisis, on the history of fossil fuels and American consumption patterns.

Sample:

By the 1960s, oil had found a tight little spot for itself at the centre of the global economy, but there was a growing sense that the rise of nuclear meant fossil fuels’ days were numbered. Indeed, one of the reasons scientists in the 1950s didn’t worry too much about what carbon emissions might do to the climate was because they figured this phase of human history—where we did something as weird as power ourselves by exploding the buried remains of ancient bugs and trees—was very much a temporary state of affairs. Nuclear received most of the shiny happy electrical future hype, but renewables got a look in too. After all, the first really big electrical project had been hydro, at Niagara, and wind and solar were about to start to at least talk about catching up too.

From the ‘You Couldn’t Make It Up’ Department

This from Politico:

The top U.S. military officer on Tuesday vigorously defended his phone calls with a Chinese general during the turbulent final weeks of Donald Trump’s presidency, revealing that U.S. intelligence officials believed the Chinese were “worried about an attack.”

Gen. Mark Milley, the chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told members of the Senate Armed Services Committee that his two phone calls with Chinese Gen. Li Zuocheng — one on Oct. 30 and another on Jan. 8, just two days after a pro-Trump mob stormed the Capitol — were part of his duties to “deconflict military actions, manage crisis and prevent war between great powers armed with nuclear weapons.”

The phone calls, which were first reported in the book “Peril” by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa, were intended to reassure the Chinese that the U.S. would not suddenly launch an attack. According to the authors, Milley — fearful that Trump could act erratically in his final days in office — told Li that he would warn him if the U.S. planned to attack China.

But he added that he was “not qualified to determine the mental health of the president of the United States” — a comment that was not included in his prepared remarks. In describing the calls, the book made references to long-running claims by Trump’s political opponents that the then-president was mentally unstable, especially at the end of his tenure in office as he was falsely asserting that the 2020 election was stolen from him.

Milley explained that his task when he made the calls was to “de-escalate”: he made them because he was concerned by “intelligence which caused us to believe the Chinese were worried about an attack by the U.S.”

Hmmm… Would this be the same General Milley who accompanied Trump on his Bible-brandishing stunt at Lafayette Square on June 1st? Surely not.

Tech implications of the German election

Politico’s AI Decoded newsletter has a useful heads-up on one aspect of the election result that will doubtless escape political editors.

Under CDU rule, AI was seen as an important economic booster along with quantum technologies, cloud and data. A new government run by the SPD is likely to call for stronger protections against AI, focusing more on the harms it can do than the benefits it can provide. The party currently holds court at Germany’s justice ministry, and Christian Kastrop, Germany’s state secretary at the federal ministry of justice and consumer protection, said he wanted stronger restrictions on remote biometric identification in the Commission’s proposal for the AI Act, Kastrop wants to expand prohibitions in the bill to private companies as well. The party’s manifesto also calls for “strict regulation and supervision” to ensure algorithmic decisions are transparent, nondiscriminatory and clearly and verifiably defined.

The Greens and the liberal FDP will be the kingmakers in the upcoming negotiations. When it comes to AI policy, they are largely aligned, even as they have their own AI priorities — sustainability and innovation, respectively. German MEP Svenja Hahn, who is one of the negotiators for the AI Act, belongs to the FDP. She has been a vocal advocate for a ban on facial recognition in public places. “Both the FDP and Greens have a stronger focus on citizens rights and are not in favour of, for example, facial recognition for surveillance purposes. Especially us liberals have been pushing for digital and tech policy to play a more important role in the next government,” Hahn said.

Why you should pay attention: The AI Act’s different levels of regulation for different levels of risk was based on the German data ethics commission’s “risk pyramid.” What happens in Berlin will also heavily influence what will happen in negotiations over the AI Act at the Council of the European Union. That’s true within the law, as decisions at Council have to be taken by 55 percent of EU countries who represent at least 65 percent of the bloc’s population. But as Europe’s most influential and powerful country, everyone’s looking at Germany anyway, regardless of its legal influence in Brussels.

Just another illustration of how all technology (or at any rate digital tech) is now political.

Chart of the Day

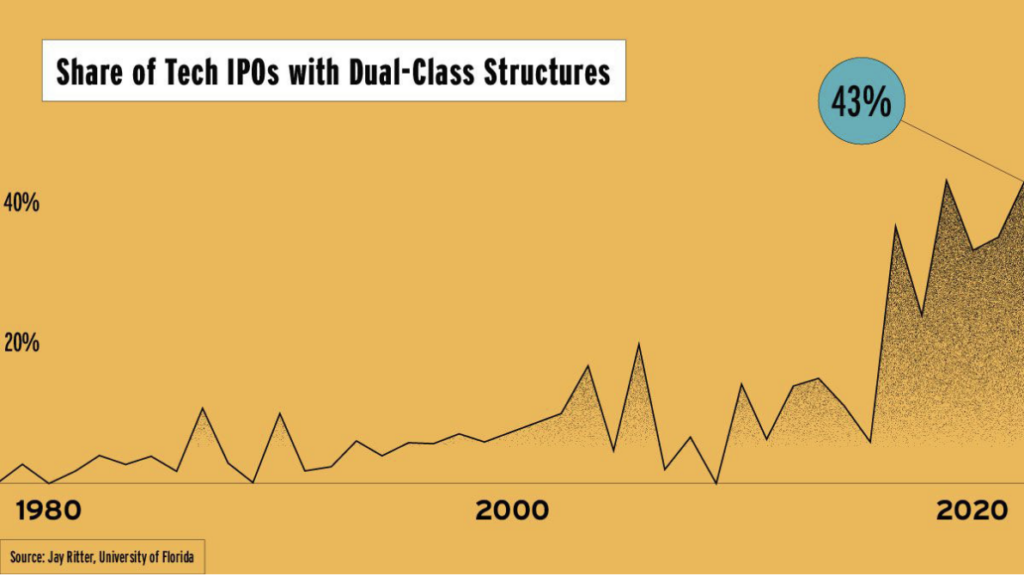

In a regular company stock structure, each share is equal to one vote.

But in a dual-class structure, certain shares have more voting power than others. These more powerful shares are reserved exclusively for company insiders and executives.

In the 80s, barely any tech companies IPO’d with a dual-class structure.

Today, tech executives love it. 43% of tech companies now go public with a dual-class structure.

(From Scott Galloway)

A Commonplace booklet

Our cat, Tilly, who always looks at me disapprovingly. In that respect, she reminds me of Angela Ripon, a celebrated BBC newsreader of whom Clive James, the celebrated TV critic, observed that “she reads the news as if it were your fault”.

…………

”According to AlgorithmWatch, a Berlin-based non-profit, at least 173 sets of AI principles have been published around the world. “ John Thornhill, FT, 29.09.2022

That’s 172 too many.

This blog is also available as a daily newsletter. If you think this might suit you better why not sign up? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-button unsubscribe if you conclude that your inbox is full enough already!