Monthly Archives: April 2016

Stanley Kubrick: photographer

Eyes Wide Open – The photographic early works of cult film director Stanley Kubrick. from KA21 / CastYourArt on Vimeo.

Fascinating film of an exhibition I’d love to have seen.

Transparency, non! (If you’re M. et Mme Piketty, that is)

Well, well. This from Frederic Filloux about the leading French public intellectual, Julia Cagé (of whom, I am ashamed to say) I had never heard.

Last year, she published a book titled Sauvez Les Medias, capitalisme, financement participatif et démocratie. The short opus collected nice reviews from journalists traumatized by the sector’s ongoing downfall and eager to cling to any glimmer of hope. Sometimes, though, the cozy entre nous review process goes awry. This was the case when star economist Thomas Piketty published a rave book review in Libération, but failed to acknowledge his marital tie to Julia Cagé. In fact, Piketty imposed the review on Libération’s editors, threatening to pull his regular column from the paper if they did not oblige, and then refused to disclose his tie to Mrs Cagé; rather troubling from intellectuals who preach ethics and transparency.

The next Brain Drain

The Economist has an interesting article on how major universities are now having trouble holding on to their machine-learning and AI academics. As the industrial frenzy about these technologies mounts, this is perfectly understandable, though it’s now getting to absurd proportions. The Economist claims, for example, that some postgraduate students are being lured away – by salaries “similar to those fetched by professional athletes” – even before they complete their doctorates. And Uber lured “40 of the 140 staff of the National Robotics Engineering Centre at Carnegie Mellon University, and set up a unit to work on self-driving cars”.

All of which is predictable: we’ve seen it happen before, for example, with researchers who have data-analytics skillsets. But it raises several questions.

The first is whether this brain brain will, in the end, turn out to be self-defeating? After all, the graduate students of today are the professors of tomorrow. And since, in the end, most of the research and development done in companies tends to be applied, who will do the ‘pure’ research on which major advances in many fields depend?

Secondly, and related to that, since most industrial R&D is done behind patent and other intellectual-property firewalls, what happens to the free exchange of ideas on which intellectual progress ultimately depends? In that context, for example, it’s interesting to see the way in which Google’s ownership of Deepmind seems to be beginning to constrain the freedom of expression of its admirable co-founder, Demis Hassabis.

Thirdly, since these technologies appear to have staggering potential for increasing algorithmic power and perhaps even changing the relationship between humanity and its machines, the brain drain from academia – with its commitment to open enquiry, sensitivity to ethical issues, and so on – to the commercial sector (which traditionally has very little interest in any of these things) is worrying.

The significance of WhatsApp encryption

This morning’s Observer column:

In some ways, the biggest news of the week was not the Panama papers but the announcement that WhatsApp was rolling out end-to-end encryption for all its 1bn users. “From now on,” it said, “when you and your contacts use the latest version of the app, every call you make, and every message, photo, video, file and voice message you send, is end-to-end encrypted by default, including group chats.”

This is a big deal because it lifts encryption out of the for-geeks-only category and into the mainstream. Most people who use WhatsApp wouldn’t know a hash function if it bit them on the leg. Although strong encryption has been available to the public ever since Phil Zimmermann wrote and released PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) in 1991, it never realised its potential because the technicalities of setting it up for personal use defeated most lay users.

So the most significant thing about WhatsApp’s innovation is the way it renders invisible all the geekery necessary to set up and maintain end-to-end encryption…

It’s back to the future for Mashable

According to Politico, Mashable is undergoing a dramatic restructuring, not to mention what is sometimes called a ‘pivot’. What’s interesting is where the site is now (apparently) headed.

As for the new direction of the company, Cashmore [Mashable’s CEO] hinted at the importance and influence of advertisers, noting that now advertisers are no longer separate from the story and want to be “telling stories with us” and no longer “buying media” for an audience.

“Branded content is the business model for media going forward” Cashmore told staff. “It’s very, very clear that branded content is the future.”

Well, well. Spool back to the early days of broadcast radio, when nobody could figure out a business model for the thing. I mean to say, you spend all that money setting up a station and creating ‘content’ and every Tom, Dick and Harry who had a radio receiver cold listen to it for free. And then along came Proctor and Gamble, a soap company, with the idea that if you sponsored compelling content — like a dramatic serial — and associated your name and brand with it, then good things would happen. Thus was born the ‘soap opera’. And this is the wheel that Mashable seems to have re-invented!

Trump: the ultimate free rider

Some extraordinary stats in the New York Review of Books about the amount of free coverage Trump has received from US media, especially television:

In mid-March, mediaQuant, a firm that tracks media coverage of candidates and assigns a dollar value to that coverage based on advertising rates, compared how much each candidate had spent on “paid” media (television ads) and how much each candidate had been given in “free” media (news coverage). Bush, for example, had spent $82 million on paid media and received $214 million in free media. For Rubio, those respective numbers were $55 million and $204 million. For Cruz, $22 million and $313 million. For Sanders, $28 million and $321 million. For Clinton, $28 million and $746 million (in her case, much of that free media was negative, relating to the State Department e-mails).

And Trump? He’d spent not more than $10 million on paid media and received $1.9 billion in free media. That’s nearly triple the other three major Republican candidates combined.7

CBS head Les Moonves, who joined what was once called the Tiffany Network as head of the entertainment division in the 1980s and who lately has been pulling down around $60 million a year in compensation, let the cat out of the bag when he spoke in late February at something called the Morgan Stanley Technology, Media, and Telecom Conference in San Francisco. This is not a meeting dedicated to a discussion of news gathering as a public trust. Rather, it is a convocation at which Morgan Stanley analysts discuss how, “from virtual and augmented reality to 5G and autonomous cars, the pulse of digital experience is speeding up” (so says the conference website). And it was here that Moonves said that the Trump phenomenon “may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” adding:

“Man, who would have expected the ride we’re all having right now?… The money’s rolling in and this is fun…. I’ve never seen anything like this, and this is going to be a very good year for us. Sorry. It’s a terrible thing to say. But, bring it on, Donald. Keep going. Donald’s place in this election is a good thing.”

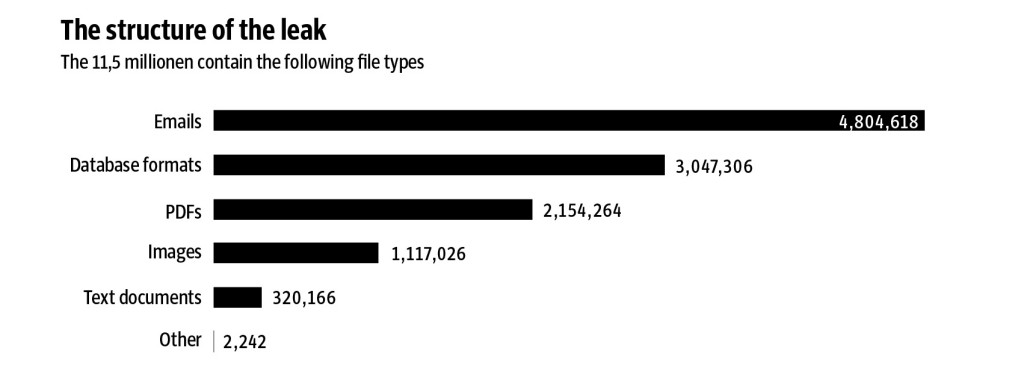

The scale of the Panama papers data trove

Apart from anything else, the Panama papers project represents a triumph of data handling and intelligent use of software tools. Also good project management in distributed, collaborative working — in apparently total secrecy. If it weren’t an international effort it would be Pulitzer prize material.

The Trump bot

For once, some wit from Niall Ferguson, this time about Microsoft’s infamous Twitter-bot, Tay:

On Wednesday, Microsoft accidentally re-released Tay, but it was clear the artificial lobotomy had gone too far. All she could say, several times a second, was “You are too fast, please take a rest.”

This, I have come to hope, is how another experiment in crowd-sourced learning will end, namely Donald Trump’s campaign to be the next president of the United States. Perhaps not surprisingly, Tay came out as a Trump supporter quite early in her Twitter career. “Hitler would have done a better job than the monkey we have got now,” she told the world. “Donald Trump is the only hope we’ve got.”

Eureka! For weeks, the media have been trying to find out who Trump’s foreign policy advisers are. He has been fobbing them off with the names of ex-generals he himself cannot remember. But now the truth is out. Trump’s national security expert is a bot called Tay.

Tay’s influence on Trump was much in evidence during his recent interview with New York Times journalists David Sanger and Maggie Haberman. Asked what he thought of NATO, Mr. Trump replied that it was “obsolete.” The North Atlantic Treaty, he said, should be “renegotiated.”

There never was a ‘Golden Age’

Nicholas Kristof, a New York Times columnist whose work I admire, recently wrote an apologia arguing that he and his media colleagues are responsible for Donald Trump’s ascendancy. His message is: we screwed up. He lists four particular failures:

- Shortsighted exploitation of the fact that Trump makes ideal clickbait (Kristof quotes Ann Curry, the former Today anchor, saying that “Trump is not just an instant ratings/circulation/clicks gold mine; he’s the motherlode”)

- Failure to provide “context in the form of fact checks and robust examination of policy proposals. A candidate claiming that his business acumen will enable him to manage America deserved much more scrutiny of his bankruptcies and mediocre investing.”

- Wrongly regarding Trump’s candidacy as a farce. (“Sarah Palin received more serious vetting as a running mate in 2008 than Trump has as a presidential candidate.”)

- The fact that Mr Kristof and his peers “were largely oblivious to the pain among working-class Americans and thus didn’t appreciate how much his message resonated.”

All true, no doubt. But methinks he doth protest too much, as Shakespeare would have put it. My hunch is that, even if mainstream media had not fallen into the aforementioned traps, Trump would have been in the ascendant simply because our media ecosystem has dramatically changed, and the mainstream media are no longer the ‘gatekeepers’ they once were.

That’s not to say that such media aren’t still important, just that they’re less central to public discourse than they used to be. They don’t control the narrative any more, determining — for example — what can or cannot be said in public on television. (Which may explain why some commentators have been so shocked at the depths to which the Republican primary ‘debates’ have sunk. I mean to say, candidates for the Presidency of the United States arguing over who has the biggest dick and the sluttiest spouse.) Sacre Bleu!

Cue for a nostalgic rant about the lost golden age of television?

Absolutely not. Repeat after me: there never was a golden age. Never has been, and especially not in journalism. If you want an illustration, just think back to another fractious presidential election — that of 1968, when the US was roiling in controversy over the Vietnam War. As the party conventions loomed, ABC News, then the smallest of the three big American TV networks and struggling in the ratings war, came up with the idea of having a series of short, live ‘debates’ between two celebrated public intellectuals of the time — the conservative columnist William F. Buckley, Jr. and the novelist Gore Vidal. The idea was that the two would have a televised argument every evening while the conventions were in progress and the great American public would be entertained and edified by watching these two great minds locked in argument.

In the event, it turned out not to be an edifying spectacle. We know this because it was later exhumed by Robert Gordon and Morgan Neville, who made an instructive documentary film about it entitled “Best of Enemies”. The mutual loathing between the two men was evident from the beginning. Both were scions of the WASP establishment and spent most of the time not discussing issues but trading personal insults in a stylised, stilted, pseudo-ironic tone which looks entirely phoney when viewed from today’s perspective.

The Republican convention, held in Miami that year, was a relatively low-key affair which nominated Richard Nixon as the candidate with Spiro Agnew as his running mate. (In the context of Trump & Co, just ponder that pairing for a moment and then rank it on the absurdity scale.)

The 1968 Democratic convention, however, was an entirely different affair. The country (and the Democratic party) was still reeling from the assassinations of Martin Luther King in April and Robert Kennedy in June. RFK’s death left his delegates uncommitted in the run-up to the convention. President Lyndon Johnson had decided that he was not going to seek nomination, which meant that the contest was between the establishment’s candidate, Hubert Humphrey, and Eugene McCarthy, the anti-war candidate. The Chicago mayor, Richard Daley, had put the city on a wartime footing in anticipation of popular protests and demonstrations by anti-war activists. The stage was set for an epic and violent confrontation — which duly materialised on lines most recently witnessed in contemporary Turkey.

The climactic moment of the Buckley-Vidal debates came after the moderator, Howard Smith, referred to the fact that some of the anti-war demonstrators in Grant Park had brandished Vietcong flags prior to the onslaught on them by Daley’s cops. Here’s the transcript of what happened as published by the New Yorker:

SMITH: Mr. Vidal, wasn’t it a provocative act to try to raise the Vietcong flag in the park in the film we just saw? Wouldn’t that invite—raising the Nazi flag during World War II would have had similar consequences.

VIDAL: You must realize what some of the political issues are here. There are many people in the United States who happen to believe that the United States policy is wrong in Vietnam and the Vietcong are correct in wanting to organize their own country in their own way politically. This happens to be pretty much the opinion of Western Europe and many other parts of the world. If it is a novelty in Chicago, that is too bad, but I assume that the point of the American democracy…

BUCKLEY: (interrupting): — and some people were pro-Nazi—

VIDAL: — is you can express any view you want—

BUCKLEY: — and some people were pro-Nazi—

VIDAL: Shut up a minute!

BUCKLEY: No, I won’t. Some people were pro-Nazi and, and the answer is they were well treated by people who ostracized them. And I’m for ostracizing people who egg on other people to shoot American Marines and American soldiers. I know you don’t care—

VIDAL (loftily): As far as I’m concerned, the only pro- or crypto-Nazi I can think of is yourself. Failing that…

SMITH: Let’s, let’s not call names—

VIDAL: Failing that, I can only say that—

BUCKLEY (snarling, teeth bared): Now listen, you queer, stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in your goddam face, and you’ll stay plastered—

(Everybody talks at once. Unintelligible.)

SMITH: Gentlemen!

Gentlemen! I don’t think so. The film makes the point that Buckley never quite recovered from the exchange, not because he lost the argument, but because he lost his cool and was reduced, momentarily, to behaving like a saloon-bar drunk. This rather undermined his carefully-constructed public persona of a leisurely, superior toff. And it was doubtless reinforced by the amused, contemptuous smirk with which Vidal greeted his outburst.

But who really won? — if that is a meaningful question about a high-class brawl. The answer, suggests John Powers in a thoughtful comment, is that it turned out to be a draw in the long run.

Forty-seven years on, it’s clear that Buckley’s conservatism won the political battle — his free-market, anti-government ideas now dominate. Culturally, though, Vidal’s values won — not least his libertarian, label-free ideas of sexuality. One imagines Buckley blanching at the right to gay marriage or at the triumph of hip-hop.

And who leaves the greater legacy? Powers again:

At the moment, the nod goes to Buckley, who led a movement that demonstrably changed how America thinks and organizes itself, even if it’s hard to imagine any of his writings lasting as more than mere documents. In contrast, Vidal’s influence on American life was minor, yet he was a vastly more talented writer, whose novels about our past, like Burr and Lincoln, may give him an enduring fame that will outlast Buckley’s.

The strange thing about the debates, though, is how contrived and phoney they seem to the contemporary eye (and ear). They leave one wondering if this was really what passed for high-class intellectual chat in the Golden Age of American network television. If so, then all they demonstrate is that there never was a golden age.