Now available here.

Thanks to Brian for the link.

Now available here.

Thanks to Brian for the link.

How does the Internet look like? How does it evolve?

DIMES is a distributed scientific research project, aimed to study the structure and topology of the Internet, with the help of a volunteer community (similar in spirit to projects such as SETI@Home).

Due to the way the Internet is engineered, distributing the Internet mapping effort is very important, and the only efficient way to measure the Internet structure is by asking you to participate. What we ask is not so much your CPU or bandwidth (which we hardly consume), but rather, your location. The more places we’ll have presence in, the more accurate our maps will be. Understanding the structure and function of the Internet is an important research task, that will allow to make the Internet a better place for all of us.

The DIMES agent performs Internet measurements such as TRACEROUTE and PING at a low rate, consuming about 1KB/s. The agent DOES NOT send any information about its host’s activity/personal data, and sends ONLY the results of its own measurements. Aside from giving a good feeling, running the DIMES agent will also provide you with maps of how the Internet looks from your home (currently) and will (in the future) provide you with a personalized ‘Internet weather report’ and other user-focused features.

We are welcoming DIMES pioneers who want to participate in our initial measurement effort and help us discover the Internet. If you want to suggest ideas or comment on DIMES you are welcome to visit our forums.

[Source]

Interesting Tech Review report…

The increased use of peer-to-peer communications could improve the overall capacity of the Internet and make it run much more smoothly. That’s the conclusion of a novel study mapping the structure of the Internet.

It’s the first study to look at how the Internet is organized in terms of function, as well as how it’s connected, says Shai Carmi, a physicist who took part in the research at the Bar Ilan University, in Israel. “This gives the most complete picture of the Internet available today,” he says.

While efforts have been made previously to plot the topological structure in terms of the connections between Internet nodes–computer networks or Internet Service Providers that act as relay stations for carrying information about the Net–none have taken into account the role that these connections play. “Some nodes may not be as important as other nodes,” says Carmi.

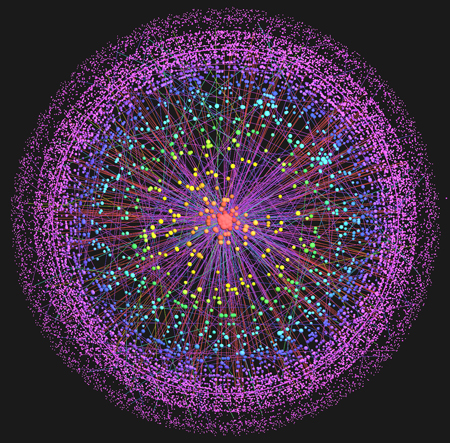

The researchers’ results depict the Internet as consisting of a dense core of 80 or so critical nodes surrounded by an outer shell of 5,000 sparsely connected, isolated nodes that are very much dependent upon this core. Separating the core from the outer shell are approximately 15,000 peer-connected and self-sufficient nodes.

Take away the core, and an interesting thing happens: about 30 percent of the nodes from the outer shell become completely cut off. But the remaining 70 percent can continue communicating because the middle region has enough peer-connected nodes to bypass the core.

With the core connected, any node is able to communicate with any other node within about four links. “If the core is removed, it takes about seven or eight links,” says Carmi. It’s a slower trip, but the data still gets there. Carmi believes we should take advantage of these alternate pathways to try to stop the core of the Internet from clogging up. “It can improve the efficiency of the Internet because the core would be less congested,” he says.