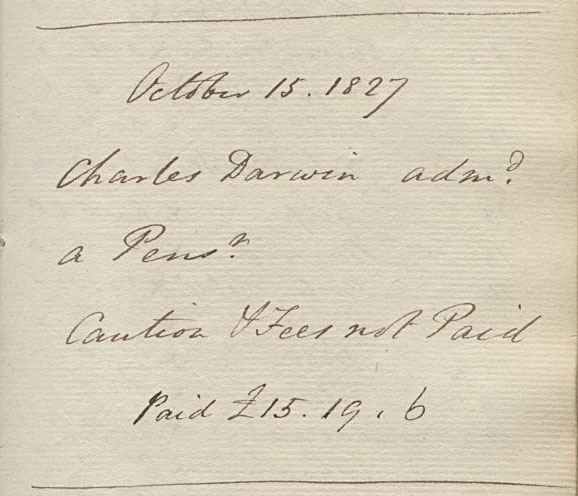

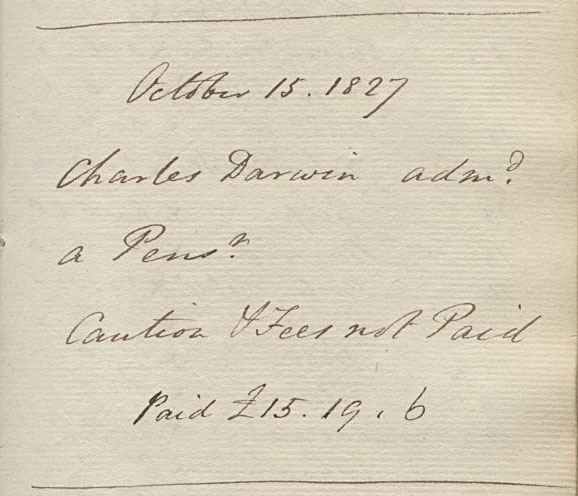

This is the entry from the Admissions Book of Christ’s College, Cambridge for 1827 confirming the admission of Charles Darwin as an undergraduate. It’s just one of the amazing riches to be found on The complete work of Charles Darwin online.

This is the entry from the Admissions Book of Christ’s College, Cambridge for 1827 confirming the admission of Charles Darwin as an undergraduate. It’s just one of the amazing riches to be found on The complete work of Charles Darwin online.

Steven Levy has an interesting interview with Steve Jobs about the iPod (which is going to be five years old soon). Sample:

Levy: Other companies had already tried to make a hard disk drive music player. Why did Apple get it right?

Jobs: We had the hardware expertise, the industrial design expertise and the software expertise, including iTunes. One of the biggest insights we have was that we decided not to try to manage your music library on the iPod, but to manage it in iTunes. Other companies tried to do everything on the device itself and made it so complicated that it was useless.

A segment about escalating sectarian violence in Iraq on the February 23 edition of Fox News’ Your World with Neil Cavuto featured onscreen captions that read: ” ‘Upside’ To Civil War?” and “All-Out Civil War in Iraq: Could It Be a Good Thing?”

The segment, guest-hosted by Fox News Live (noon-1:30 pm hour ET) anchor David Asman, featured commentary by Fox News military analyst Lt. Col. Bill Cowan and Center for American Progress senior fellow Col. P.J. Crowley.

I particularly like the idea that an all-out civil war could have an “upside”. For whom, exactly?

[Source]

Interesting essay on Terry Eagleton in The Chronicle of Higher Education…

Literary theorists, and probably other scholars, might be divided into two types: settlers and wanderers. The settlers stay put, “hovering one inch” over a set of issues or topics, as Paul de Man, the most influential theorist of the 1970s, remarked in an interview. Their work, through the course of their careers, claims ownership of a specific intellectual turf. The wanderers are more restless, starting with one approach or field but leaving it behind for the next foray. Their work takes the shape of serial engagements, more oriented toward climatic currents. The distinction is not between expert and generalist, or, in Isaiah Berlin’s distinction, between knowing one thing like a hedgehog and knowing many things like a fox; it is a different application of expertise.

[…]

Terry Eagleton has been a quintessential wanderer. Eagleton is probably the most well-known literary critic in Britain and the most frequently read expositor of literary theory in the world. His greatest influence in the United States has been through his deft surveys, variously on poststructural theory, Marxist criticism, the history of the public sphere, aesthetics, ideology, and postmodernism. His 1983 book, Literary Theory: An Introduction, which made readable and even entertaining the new currents in theory and which has been reprinted nearly 20 times, was a text that almost every literature student thumbed through during the 80s and 90s, and it still holds a spot in the otherwise sparse criticism sections of the local Barnes and Noble. His public position in Britain is such that Prince Charles once deemed him “that dreadful Terry Eagleton.” Not every literary theorist has received such public notice.

Frank Kermode once told me about a lecture tour he did in China at the behest of the British Council. In every university, he was listened to by rapt, serried ranks of Chinese students. In vain did the translator try to elicit questions from these awestruck audiences. Finally, after the final lecture, the head of the host institution begged students to ask at least one question of their very distinguished visitor.

Eventually, a shy student stood up and said to Frank: “Do you know Telly Eagleton?”

I spent most of last Sunday afternoon laboriously trimming the big beech hedge that is one of the glories of our garden. Then I made some coffee and lit a cigar and sat down to admire my handiwork — and immediately noticed that I had missed not just those straggly bits on the top edge, but also the TV aerial that appears to have grown out of the hedge when I wasn’t looking.

Which just goes to show that it all depends on your point of view.

Thoughtful article by Brice Schneier in Wired News…

As the Facebook example illustrates, privacy is much more complex. It’s about who you choose to disclose information to, how, and for what purpose. And the key word there is “choose.” People are willing to share all sorts of information, as long as they are in control.

When Facebook unilaterally changed the rules about how personal information was revealed, it reminded people that they weren’t in control. Its 9 million members put their personal information on the site based on a set of rules about how that information would be used. It’s no wonder those members — high school and college kids who traditionally don’t care much about their own privacy — felt violated when Facebook changed the rules.

Unfortunately, Facebook can change the rules whenever it wants. Its Privacy Policy is 2,800 words long, and ends with a notice that it can change at any time. How many members ever read that policy, let alone read it regularly and check for changes?

Not that a Privacy Policy is the same as a contract. Legally, Facebook owns all data that members upload to the site. It can sell the data to advertisers, marketers and data brokers. (Note: There is no evidence that Facebook does any of this.) It can allow the police to search its databases upon request. It can add new features that change who can access what personal data, and how.

But public perception is important. The lesson here for Facebook and other companies — for Google and MySpace and AOL and everyone else who hosts our e-mails and webpages and chat sessions — is that people believe they own their data. Even though the user agreement might technically give companies the right to sell the data, change the access rules to that data or otherwise own that data, we — the users — believe otherwise. And when we who are affected by those actions start expressing our views — watch out.

Hmmm… I’ve been looking at the Facebook privacy statement and it seems to me to be more reasonable that I had expected from reading Schneier’s piece. Also — unusually — it is written in plain English rather than legalese.

Nevertheless, I agree with Schneier’s general conclusion:

The lesson for Facebook members might be even more jarring: If they think they have control over their data, they’re only deluding themselves. They can rebel against Facebook for changing the rules, but the rules have changed, regardless of what the company does.

Whenever you put data on a computer, you lose some control over it. And when you put it on the internet, you lose a lot of control over it. News Feeds brought Facebook members face to face with the full implications of putting their personal information on Facebook.

Shock, horror! Programmers get bored or fed up and write rude words when commenting code. Nice piece in The Register.

Thanks to Bill Thompson for the link.

Well, well! The Observer reports that

Flat taxes fail to boost revenues, as their advocates claim, and are likely to be abandoned by the countries that have introduced them, according to research published by the International Monetary Fund.

‘The question is not so much whether more countries will adopt a flat tax, as whether those that have will move away from it,’ the study says, after examining the experience of eight economies that have introduced the policy since the mid-Nineties.

Sweeping away variable tax bands and replacing them with a single rate has long been a dream of right-wing economists. Since a number of Eastern European governments introduced flat taxes, support for them has grown in the UK, and shadow Chancellor George Osborne has flirted with the idea.

But the IMF analysts who carried out the research cast doubt on the main advantage claimed for flat taxes: that they increase revenues by allowing people to pocket more of their hard-earned cash, and thus persuade them to work harder.This is the so-called ‘Laffer effect’ named after US economist Arthur Laffer. But the authors say: ‘In no case does there appear to have been a Laffer effect: these reforms have not set off effects strong enough for them to pay for themselves.’

Nice profile of Micheal Moritz…

Michael Moritz has a few simple rules for investing in internet start-ups: look for people who are pursuing their own ideas for doing something better; prefer youth to maturity; ignore business plans looking a few years ahead; and avoid anyone wearing Armani T-shirts, loafers with no socks or who uses words like ‘synergy’, ‘no-brainer’ or ‘slam-dunk’.

Moritz is worth listening to. The 51-year-old Welshman is one of the duo running Sequoia Capital, the Silicon Valley venture capital firm that has just made an estimated $480m profit in less than a year by backing YouTube, the video-sharing business this week acquired by Google. And it is not the firm’s only success: it was one of the only two venture capital firms to back Google itself, investing $12.5m in the start-up business; its 10 per cent stake is now worth more than $12bn. Its other investments read like a who’s who of the technology business: PayPal, Yahoo, eBay, Apple, Cisco.Small wonder that Moritz tops the list of technology deal-makers produced by Forbes, the US business magazine – or that his own wealth, estimated at £518m in the Sunday Times Rich List, makes him the sixth richest internet millionaire….

This morning’s Observer column…

Before he hit the jackpot with YouTube, Jawed (like Hurley and Chen) had made a pile from his earlier involvement in PayPal, the online payment system bought by eBay in 2002 for $1.5bn. His share of the $1.65bn paid by Google for YouTube will reportedly be less than theirs, but it should still be sufficient to fund a private squadron of F-16s. And yet the lad chooses to bank the cash and return to considering ‘algorithms for edit distance on permutations’ and other arcane matters engaging students on the Stanford CS300 course. His one concession to the events of the last week was to cancel the seminar he had been scheduled to give on Thursday on ‘YouTube: from concept to hyper-growth’.

If Jawed has started a trend, who knows where it will end? Traditionally, university professors in elite US institutions find students a tiresome distraction from important work like private consulting, appearing on television and testifying before Congressional committees. For these superprofs, the really important people – the folks they have to suck up to – are rich alumni who have made good in the corporate world. But now a terrible prospect looms – US academics may in future have to pander to their students. Perhaps it will eventually become known as sucking down?