I’ve had a few goes at this (for example here and here) but Frederic Filloux has done an even better job:

Setting aside the need to fix its current PR nightmare, Facebook has no objective interest in fixing its fake stories problem.

In the end, it all boils down to this:

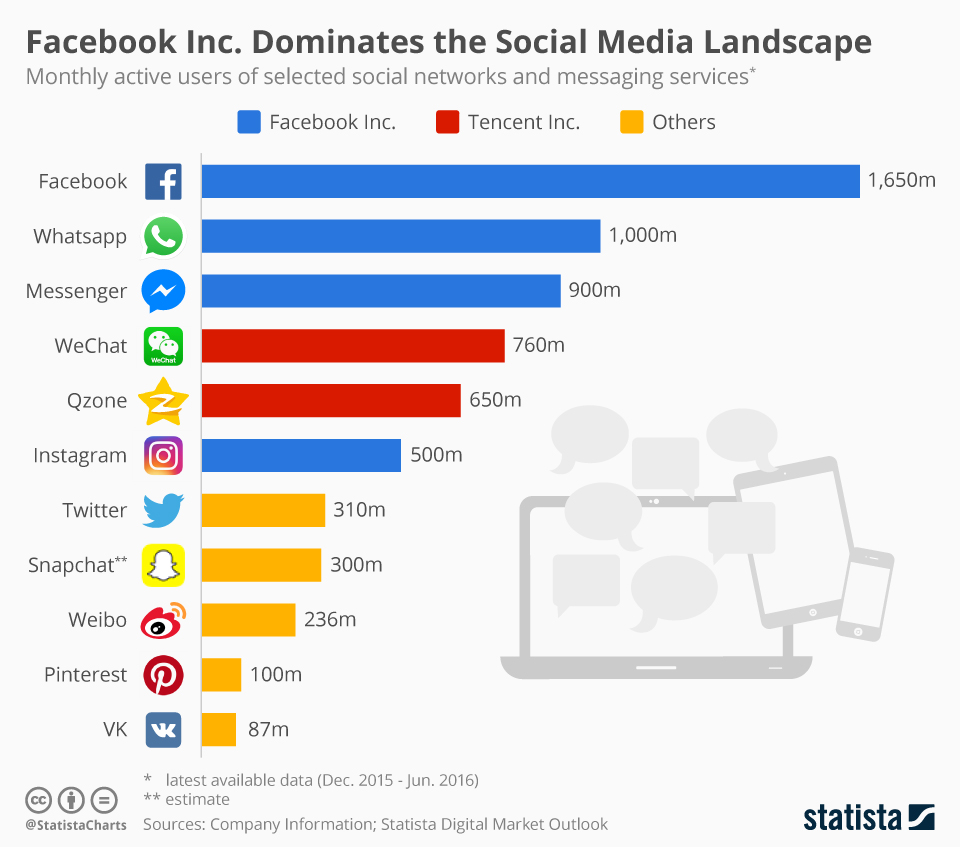

Facebook is above all an advertising machine. A fantastic one. I encourage everyone to explore its spectacular advertising interface and, even better, to spend a few bucks to boost a post, or build an ad. Its power, reach, granularity and overall efficiency are dizzying.

Facebook’s revenue system depends on a single parameter: page views. Pages views come from sharing. Which page criteria lead to the best sharing volumes?

You know the answer:

- Emotions, preferably positive ones

- Fun – LOLcats, listicles, cartoons,…

- Proximity – stuff from friends and family

- Affinities – stuff that resonates with your feelings, values and politics (and thereby locks you into your own personal filter bubble)

Sharing is key to Facebook’s business model because it leads to higher page consumption which, in turn, leads to multiple personalised advertising exposures.

It’s a great post, well worth reading in full. What I particularly enjoyed is Filloux’s takedown of young Zuckerberg’s cant about connecting everybody. This is what the lad said:

We stand for connecting every person. For a global community. For bringing people together. For giving all people a voice. For a free flow of ideas and culture across nations. And this idea of connecting the world has gotten stronger over the last century. You can now travel almost anywhere in the world in less than a day. Countries trade more openly and cooperate more easily than ever. And the Internet has enabled all of us to access and share more ideas and information than ever before. We’ve gone from a world of isolated communities to one global community, and we’re all better off for it.

Sounds good? Only problem: it’s BS. As Filloux puts it:

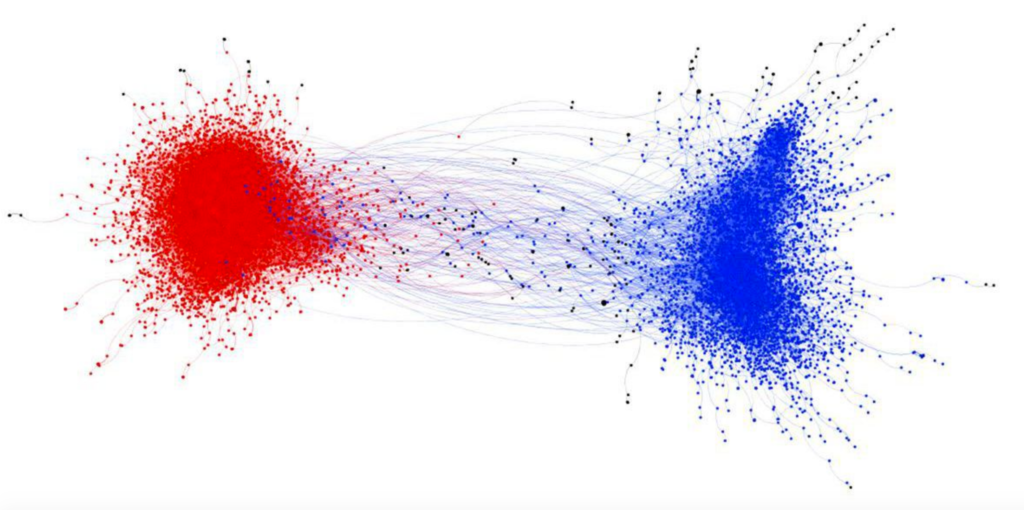

Facebook might have created a “global community” but its components are utterly segregated and fragmented.

Facebook is made up of dozens of millions of groups carefully designed to share the same views and opinions. Each group is protected against ideological infiltration from other cohorts. Maintaining the integrity of these walls is the primary mission of Facebook’s algorithm.

Yep. QED.