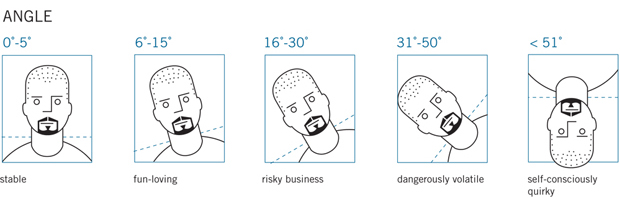

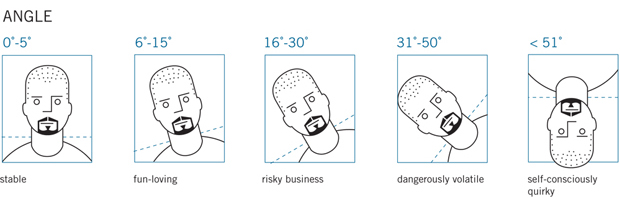

Apropos my column about the Facebook photographic style, FastCompany has a nice piece on the subject — and a really comprehensive chart.

Apropos my column about the Facebook photographic style, FastCompany has a nice piece on the subject — and a really comprehensive chart.

Lovely, perceptive review by Larry Lessig of the Facebook movie. From ‘The New Republic’.

As with every one of his extraordinary works, Sorkin crafted dialogue for an as-yet-not-evolved species of humans—ordinary people, here students, who talk perpetually with the wit and brilliance of George Bernard Shaw or Bertrand Russell. (I’m a Harvard professor. Trust me: The students don’t speak this language.) With that script, and with a massive hand from the film’s director, David Fincher, he helped steer an intelligent, beautiful, and compelling film through to completion. You will see this movie, and you should. As a film, visually and rhythmically, and as a story, dramatically, the work earns its place in the history of the field.

But as a story about Facebook, it is deeply, deeply flawed. As I watched the film, and considered what it missed, it struck me that there was more than a hint of self-congratulatory contempt in the motives behind how this story was told. Imagine a jester from King George III’s court, charged in 1790 with writing a comedy about the new American Republic. That comedy would show the new Republic through the eyes of the old. It would dress up the story with familiar figures—an aristocracy, or a wannabe aristocracy, with grand estates, but none remotely as grand as in England. The message would be, “Fear not, there’s no reason to go. The new world is silly at best, deeply degenerate, at worst.”

Not every account of a new world suffers like this. Alexis de Tocqueville showed the old world there was more here than there. But Sorkin is no Tocqueville. Indeed, he simply hasn’t a clue to the real secret sauce in the story he is trying to tell. And the ramifications of this misunderstanding go well beyond the multiplex…

And here’s the best bit:

But the most frustrating bit of The Social Network is not its obliviousness to the silliness of modern American law. It is its failure to even mention the real magic behind the Facebook story. In interviews given after making the film, Sorkin boasts about his ignorance of the Internet. That ignorance shows. This is like a film about the atomic bomb which never even introduces the idea that an explosion produced through atomic fission is importantly different from an explosion produced by dynamite. Instead, we’re just shown a big explosion ($25 billion in market capitalization—that’s a lot of dynamite!) and expected to grok (the word us geek-wannabes use to show you we know of what we speak) the world of difference this innovation in bombs entails.

What is important in Zuckerberg’s story is not that he’s a boy genius. He plainly is, but many are. It’s not that he’s a socially clumsy (relative to the Harvard elite) boy genius. Every one of them is. And it’s not that he invented an amazing product through hard work and insight that millions love. The history of American entrepreneurism is just that history, told with different technologies at different times and places.

Instead, what’s important here is that Zuckerberg’s genius could be embraced by half-a-billion people within six years of its first being launched, without (and here is the critical bit) asking permission of anyone.

Yep.

The Editor of the UK edition of Wired magazine isn’t on Facebook. Here’s why.

Christopher Caldwell had a typically thoughtful column in yesterday’s Financial Times, about the case of the Washington Post sportswriter, Mike Wise, and his Twitter experiments.

Mr Wise has built a reputation as one of America’s top basketball reporters. He has a radio show. He does interviews. And – fatefully – he stays in contact with his readers through Twitter. On Monday, Mr Wise “tweeted” three fake news stories. One concerned how long a suspension Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger would receive for alleged off-field misconduct. Mr Wise wrote: “Roethlisberger will get five games, I’m told.” The Miami Herald, The Baltimore Sun and NBC’s Pro Football Talk blog all cited the tweet.

Mr Wise then revealed that the story was a hoax – or, to put it charitably, a piece of freelance sociological fieldwork. Mr Wise had been critical of online “aggregators” who do not source their own stories or check facts independently. He explained, in an apology posted on Twitter, that he had been trying to “test the accuracy of social media reporting”.

The Post, however, didn’t see the joke and suspended him for a month. The paper’s argument was that his position as a senior writer in a major newspaper effectively meant that Mr Wise was not free to do what you or I might be free to do.

Mr Caldwell explores the complexities of the case. He points out that, in the first place, Wise’s “test” wasn’t exactly well-designed. What he wanted to test was the willingness of online aggregators to repeat allegations/stories without bothering to check them. But you might say that many people would think it reasonable to pass on without checking something they’ve got from a respected and knowledgeable source. In my case, for example, I’d be less concerned to check something from Nick Robinson’s blog than a rumour that I’d read in one of the UL political blogs. And I guess that if I were interested in American sports then I’d feel the same about Mr Wise.

But what of the Post‘s argument: that it has a right to demand certain kinds of behaviour from its journalists even in their private, or semi-private lives? It sounds a bit like the requirement that police officers should be circumspect in their off-duty behaviour. Here’s Caldwell again:

The real stakes of Mr Wise’s prank do not concern social journalism. They concern the broader matter of what belongs to institutions and what belongs to their members (or employees), and what each is entitled to demand of the other. Politics is always reminding us that this line is very hard to draw. When Newt Gingrich signed a multimillion-dollar book contract after the Republicans won the midterm elections of 1994, attention focused on Rupert Murdoch’s ownership of the publishing company that was paying him. An equally pertinent question, though, was whether Mr Gingrich was worth all that money because he was Newt Gingrich or because he was the presumptive Speaker of the House. If the latter, then he was arguably selling something that did not belong to him. The same goes for Barack Obama’s signing a multi-book contract after his election as Illinois senator in 2004.

Mr Wise appears to understand what he did wrong in just these terms. “I made a horrendous mistake,” he wrote, “using my Twitter account that identifies me as a Washington Post columnist.” Since it was a personal account, some might say that he hurt no one but himself. This is a line of thinking that the Post rightly moved to squelch. Mr Wise is thought of as a Washington Post columnist whether he identifies himself that way or not. This entitles the paper to make certain demands. The sports editor, Matthew Vita, circulated a copy of the Post’s new-media guidelines, which read, in part: “When you use social media, remember that you are representing The Washington Post, even if you are using your own account … All Washington Post journalists relinquish some of the personal privileges of private citizens. Post journalists must recognise that any content associated with them in an online social network is, for practical purposes, the equivalent of what appears beneath their bylines in the newspaper or on our website.”

But what if ‘social media’ become the dominant way in which social life is lived in the future? The Post probably wouldn’t feel entitled to complain if Mr Wise had tried his ruse in his local pub or golf club. It’s the fact that he did it in an arena that is ambiguously both public and private that causes the problem. So…

The internet and the new media are commonly described as a liberating, individualising force. In many respects, though, they are replacing informal relationships with surveilled ones. Mr Wise was wrong to put up his phoney tweets. The Post was within its rights to discipline him. But it is hard not to worry about the principles laid down in the process of doing so. The net result of the internet may be to invite the boss into what used to be the stronghold of one’s private life.

Come to think of it, though, this is a case where there’s an interesting difference between Facebook and Twitter. The latter is definitely a ‘public’ space — unless one explicitly protects one’s tweets, and I guess Mr Wise doesn’t. The Post might have had more trouble if he’d conducted his experiment in Facebook, where only his ‘friends’ would have seen it. Hmmm…

Anyway, this was a terrific column, by a terrific columnist.

Bruce Schneier has come up with what seems to me to be a really useful taxonomy — first presented at the Internet Governance Forum meeting last November, and again — revised — at an OECD workshop on the role of Internet intermediaries in June.

1. Service data is the data you give to a social networking site in order to use it. Such data might include your legal name, your age, and your credit-card number.

2. Disclosed data is what you post on your own pages: blog entries, photographs, messages, comments, and so on.

3. Entrusted data is what you post on other people’s pages. It’s basically the same stuff as disclosed data, but the difference is that you don’t have control over the data once you post it — another user does.

4. Incidental data is what other people post about you: a paragraph about you that someone else writes, a picture of you that someone else takes and posts. Again, it’s basically the same stuff as disclosed data, but the difference is that you don’t have control over it, and you didn’t create it in the first place.

5. Behavioral data is data the site collects about your habits by recording what you do and who you do it with. It might include games you play, topics you write about, news articles you access (and what that says about your political leanings), and so on.

6. Derived data is data about you that is derived from all the other data. For example, if 80 percent of your friends self-identify as gay, you’re likely gay yourself.

Yep. According to Mr Zuckerberg,

As of this morning, 500 million people all around the world are actively using Facebook to stay connected with their friends and the people around them.

Yay! And some of those 500 million may one day come to regret some aspects of their social networking.

According to a recent survey by Microsoft, 75 percent of U.S. recruiters and human-resource professionals report that their companies require them to do online research about candidates, and many use a range of sites when scrutinizing applicants — including search engines, social-networking sites, photo- and video-sharing sites, personal Web sites and blogs, Twitter and online-gaming sites. Seventy percent of U.S. recruiters report that they have rejected candidates because of information found online, like photos and discussion-board conversations and membership in controversial groups.

From The Register.

Elevation Partners, the private equity firm backed by bad-backed U2 frontman Bono, has stumped up $120m for just over 0.5 per cent of Facebook.

The deal values the dominant social network at $23bn, and takes Elevation Partners' total stake to 1.5 per cent, having invested $90m at a $9bn valuation last year.

Reports earlier this month claimed Facebook's sales were between $700m and $800m last year, so Bono and friends reckon it's worth about 29 times revenue at the moment. Which is a lot.

The widely-held assumption is that Facebook aims to IPO in the next couple of years, when Elevation Partners and the other private interests who have paid its running costs since 2004 will cash in.

Bono's fund could use a hit. It sank hundreds of millions into Palm's attempted revival, which ended in a fire sale to HP this year…

For anyone seeking perspective on the social-networking business, the news that AOL has sold Bebo for what sounds like a fire-sale price should be required reading.

AOL is set to reap an "exceptionally uninspiring" sum for Bebo, the moribund social networking site for which it paid $850m just two years ago.

The Wall Street Journal says a sale could be announced today, with the likely buyer Criterion Capital Partners LLC of Studio City California. This is an interesting location – a suburb of LA nowhere near Silicon Valley.

The deal was confirmed this afternoon, though no details of the price were revealed.

The buyer apparently specialises in turning around companies with revenues of $3m to $30m, which doesn't say too much for the state of Bebo.

Still, it's AOL that is taking a bath on the deal. The journal, ahead of the official announcement, quoted one source familiar with the negotiations who said AOL's price was "an exceptionally uninspiring number" with almost total "value destruction".

As the say in the small print, the value of investments may go down as well as up.