Saturday 13 June

Quote of the Day

Some on the left drew a strange consolation from Trump’s hostility to foreign wars, as if it meant he could be a tactical ally against American imperialism. They failed to see that he wanted to wage war at home: his furious inauguration speech with its talk of ‘American carnage’ was a declaration of war on urban racial liberalism, especially as represented by New York, the city that had rejected him.

- Adam Shatz, “America Explodes”, LRB 18 June, 2020

The West’s ‘China problem’

I started the day reading Peter Oborne’s piece on whether China will replace Islam as the West’s new enemy — and then got sucked into the rabbit-hole of whether we are sliding into a new Cold War, with China playing the role that the Soviet Union played in the old days. This is all about geopolitics, of course, about which I know little. But if you write about digital technology, as I do, this emerging Cold War is a perennial puzzle that pops up everywhere. For example, in:

- the discussions about whether Huawei kit should be allowed in Western 5G networks;

- whether we should be concerned about becoming addicted to Zoom, a company with a sizeable chunk of its workforce and infrastructure based in China;

- what to make of China’s increasing technological assertiveness at the ITU over changing the centrals protocols of the TCP/IP-based Internet we use today

- anxieties in (mostly-US companies and the US government) about the inbuilt advantages an authoritarian regime has in fostering the development of ‘AI’ (aka machine-learning) technology, the essential feedstock for which is unlimited volumes of user data — as compared with the way our liberal reservations about privacy and civil rights hobbles our tech giants.

- the strange and enduring legacy of old Cold War attitudes in the Western military-industrial complex which continually obsesses about Russia rather than China.

This last factor is particularly weird. In the immediate post-war period, we lived in a genuinely bi-polar world, with competition between two different economic and ideological systems — the Soviet, centrally-planned one, and the Western liberal capitalist one.

As it happens, we in the West greatly over-estimated the capacity of the Soviet system, perhaps because it seemed to be very good at some things — nuclear weapons development and space science in particular. In part we owe the Internet to the fright the US received when in 1957 the USSR launched Sputnik, the first earth-orbiting satellite. This, among other things, led to the establishment of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) in the Pentagon, which was the organisation that conceived and funded Arpanet, the precursor of today’s Internet.

Nevertheless, it remained true that the bi-polar world into which I was born was based on an ongoing contest between two socio-economic systems which could be — and were often — seen as genuine alternatives.

This bi-polar world evaporated in 1989 when the Berlin Wall came down and two years later the USSR imploded, leaving the Western model apparently triumphant. This was the moment that coincided with the publication of Francis Fukuyama’s ‘End of History’ essay, which argued that the post-1917 ideological competition about the best way to organise society had been decisively resolved with liberal democracy as the winning candidate. This was an overly-simplistic reading of Fukuyama, but what was indisputable was that, post-1989, we moved into a uni-polar world, with the US as the reigning hyper power, able to do exactly as it pleased. Which it did, including launching a disastrous war in Iraq on a pretext, and further destabilising the Middle East as a consequence.

But even before 1989, things were beginning to change elsewhere in the world. In 1978, in particular, as Laurie Macfarlane points out,

Deng Xiaoping became China’s new paramount leader, after outmanoeuvring Mao’s chosen successor, Hua Guofeng. Deng oversaw the country’s historic ‘Reform and Opening-up’ process, which increased the role of market incentives and opened up the Chinese economy to global trade. In the decades since, China’s economic transformation has been nothing short of astonishing.

In 1981, 88% of the Chinese population lived in extreme poverty. In the four decades since, nearly a billion people have been lifted out of poverty, leaving the figure at less than 2%. Over the same time period, the size of China’s economy increased from $195 billion – around the same size as the Spanish economy – to nearly $14 trillion today. By some measures, China’s economy has overtaken the US and is now the largest in the world. China is also home to the second largest number of Fortune 500 companies in the world, and more billionaires than Europe.

So even as the old bi-polar world was dying, a new alternative system was being born. I don’t think that Deng had many geopolitical ambitions, but his successors certainly had. And have.

China’s astonishing economic transformation has been engineered by a distinctive economic model which they call “socialism with Chinese characteristics”, combining strategic state ownership and planning with market-oriented incentives and a one-party political system to create a unique economic model that while poorly understood in the West is found interesting and perhaps attractive by a significant number of non-aligned countries.

It doesn’t look much like ’socialism’ to anyone who studies the tech sector, because the private sector accounts for the overwhelming majority of output, employment and investment in China; and there is — as Macfarlane points out, little sign of democratic workers’ control. But it’s a powerful and effective system, and — to date — it appears to be working. Which is more than could ever be said for the Soviet system.

So here we are in a bi-polar world again. But it’s nothing like its predecessor. In the old Cold War, for example, European democracies were resolutely anti-Soviet (even if they didn’t always pay their mandatory 2% of GDP into the NATO budget). But now, with China as the opposite ‘pole’ to the US, they’re much more ambivalent. As are many global companies. China’s role as the workshop of the world, and also as the fastest growing and potentially most profitable market, means that outright hostility to the new superpower looks like a self-defeating policy.

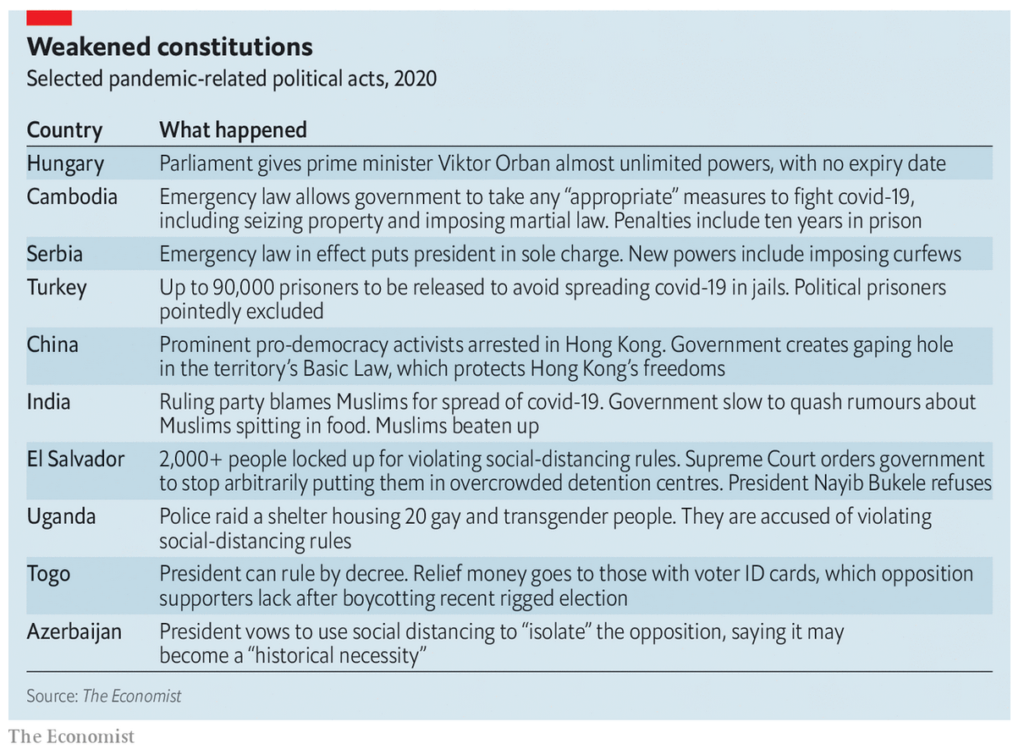

This doesn’t bother Trump, whose most desperate need is to find an enemy he can blame for the unfolding disaster of the pandemic that has occurred on his watch. And it isn’t just Trump, as Peter Oborne says:

China is being presented as the new existential enemy, just as Islam was 20 years ago. And by the very same people. The same newspaper columnists, the same think tanks, the same political parties and the same intelligence agencies.

After Huntington’s famous essay that led the charge against Muslims – or what they often call radical Islam – now they have turned their attention to the Far East.

US President Donald Trump, the world’s Muslim-basher-in-chief, has now started to attack China, rather as Bush, his Republican predecessor, attacked Iraq in 2003 and the “axis of evil” 20 years ago. During his campaign in 2016 he accused China of “raping” the US economy.

However, since the outbreak of Covid-19, Trump’s attacks have gained speed and traction. He has accused China of covering up the virus and lying about its death toll.

Leaving aside Trump, who thinks only in transactional terms and doesn’t seem to have any strategic sense, the impression one gets from the US foreign policy establishment is of hegemonic unease. The feeling that it would be disastrous if the US lost its position as the global leader in digital technology is palpable. And it’s ruthlessly exploited by the tech companies — as we saw when the Facebook boss ‘testified’ to Congress and hinted that not hampering (i.e. regulating) the tech giants is a way of ensuring the continuance of US technological hegemony.

So is American hegemony really in doubt? Writing in 2018, Adam Tooze was sceptical:

As of today, two years into the Trump presidency, it is a gross exaggeration to talk of an end to the American world order. The two pillars of its global power – military and financial – are still firmly in place. What has ended is any claim on the part of American democracy to provide a political model. This is certainly a historic break. Trump closes the chapter begun by Woodrow Wilson in the First World War, with his claim that American democracy articulated the deepest feelings of liberal humanity. A hundred years later, Trump has for ever personified the sleaziness, cynicism and sheer stupidity that dominates much of American political life. What we are facing is a radical disjunction between the continuity of basic structures of power and their political legitimation.

If America’s president mounted on a golf buggy is a suitably ludicrous emblem of our current moment, the danger is that it suggests far too pastoral a scenario: American power trundling to retirement across manicured lawns. That is not our reality. Imagine instead the president and his buggy careening around the five-acre flight deck of a $13 billion, Ford-class, nuclear-powered aircraft carrier engaged in ‘dynamic force deployment’ to the South China Sea. That better captures the surreal revival of great-power politics that hangs over the present. Whether this turns out to be a violent and futile rearguard action, or a new chapter in the age of American world power, remains to be seen.

And if you felt that this post was TL;DR. (Too long, don’t read) I perfectly understand. E.M. Forster once observed that there are two kinds of writer: those who know what they think and write it; and those who find out what they think by trying to write it. I belong mostly in the latter category.

Quarantine diary — Day 84

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if your decide that your inbox is full enough already!