As Tony Hirst points out, the fiasco of the Reinhard-Rogoff correlation that evaporated under student examination is a very good argument for open data in social science as well as in the exact sciences. But I don’t think that the full import of the screw-up has dawned on enough people. After all, our economies are being destroyed by governments who believe in the economic equivalent of fairies, and the Reinhard-Rogoff correlation (of public debt with low or zero economic growth) provided the only theoretical fig-leaf that they had. And now it’s been shown to be a transparent fig-leaf.

The Atlantic had a good go at exploring what this means:

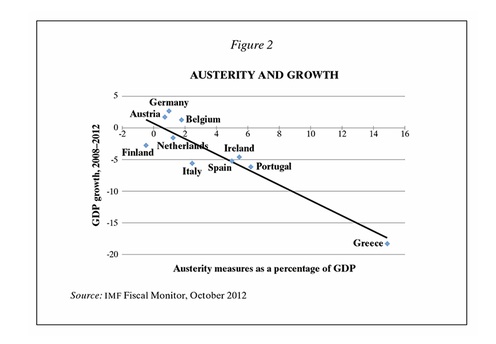

Austerity has been a policy in search of a justification ever since it began in 2010. Back then, policymakers decided it was time for policy to go back to “normal” even though the economy hadn’t, because deficits just felt too big. The only thing they needed was a theory telling them why what they were doing made sense. Of course, this wasn’t easy when unemployment was still high, and interest rates couldn’t go any lower. Alberto Alesina and Silvia Ardagna took the first stab at it, arguing that reducing deficits would increase confidence and growth in the short-run. But this had the defect of being demonstrably untrue (in addition to being based off a naïve reading of the data). Countries that tried to aggressively cut their deficits amidst their slumps didn’t recover; they fell into even deeper slumps.

Enter Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff. They gave austerity a new raison d’être by shifting the debate from the short-to-the-long-run. Reinhart and Rogoff acknowledged austerity would hurt today, but said it would help tomorrow — if it keeps governments from racking up debt of 90 percent of GDP, at which point growth supposedly slows dramatically. Now, this result was never more than just a correlation — slow growth more likely causes high debt than the reverse — but that didn’t stop policymakers from imputing totemic significance to it. That is, it became a “fact” that everybody who mattered knew was true.

Except that it wasn’t.

Austerity is back to being a policy without a justification. Not only that, but, as Paul Krugman points out, Reinhart and Rogoff’s spreadsheet misadventure has been a kind of the-austerians-have-no-clothes moment. It’s been enough that even some rather unusual suspects have turned against cutting deficits now. For one, Stanford professor John Taylor claims L’affaire Excel is why the G20, the birthplace of the global austerity movement in 2010, was more muted on fiscal targets recently.

Will this matter? Hard to say. My feeling is that British economic policy-making has been evidence-free for a long time. George Osborne & Co are driven by blind faith in nonsense, and immune to every kind of logic, including, apparently, the electoral variety. But Krugman thinks that the Excel foopah has opened a crack in their invincible ignoramce.

“My vague, unquantifiable sense”, he writes,

“is that the debacle is changing the conversation quite a lot, even among the guys in suits. And it was the coding error that did it.

Now, the truth is that the coding error isn’t the biggest story; in terms of the economics, the real point is that R-R’s results were never at all robust, both because the apparent relationship between debt and growth is fairly weak and because the correlation clearly goes at least partly the other way. But economists have been making these points for years, to no avail. It took the shock of an outright, embarrassing error to shake the faith of the Very Serious People in a result they really wanted to believe.

The point is that the next time Olli Rehn, or George Osborne, or Paul Ryan declares, sententiously, that we must have austerity because serious economists (i.e., not Krugman and friends) tell us that debt is a terrible thing, people in the audience will snicker — which they should have been doing all along, but now it has become socially acceptable.”

Yep. Sometimes laughter is the best riposte.

LATER: Sooner or later, we ought also to start sniggering whenever an economist enters the room. As a profession addicted to a pathological paradigm which wrecked the banking system, its practitioners have shown an astonishing lack of remorse about their failings. And it turns out that, having had their incompetence exposed, Reinhart and Rogoff have been displaying textbook disingenuousness, so it’s nice to see that they’re now being called out on that too.

on Edmund Burke.